• by Paula N. Johnson, M.A. • IDRA Newsletter • May 2018 •

It depends on who you ask.

Defining “Rigor”

Rigor, defined in the traditional sense, occurs in a one-size-fits-all manner. One usually associates rigor with hard or challenging. Teachers sometimes believe they are providing rigorous instruction by assigning long, complicated assignments to students that may take hours to complete. Parents are led to believe that more work means higher rigor. Students are left feeling that advanced coursework translates into overwhelmingly tough homework that leaves little time for much else.

But none of these definitions are incorporated into the policies and practices set forth by state education agencies.

State policymakers tend to define rigor as college and career readiness, measured by college or university attendance and standardized assessments (Reich, et al., 2015).

On the other hand, educational psychologists see rigor as the “extent to which educational stakeholders, including students, are oriented towards demanding coursework” (Reich et al., 2015).

And finally, content educators may define rigor in ways that reflect their individual discipline. For example, a rigorous math class would encourage students to think mathematically and use critical thinking to solve problems.

How do we quantify a set of equitable educational outcomes for all students? These abstract definitions of rigor do not provide concrete examples of what rigor looks like.

Tieken (2015) suggests a take on rigor that individualizes it to each student based on their experiences and level of development. For example, there is no cognitive challenge in presenting a problem to a student that only includes concepts he or she is already familiar with and has mastered. Similarly, students who are unsuccessful at completing a problem that is developmentally inappropriate can be mistakenly labeled as a struggling learner or low achieving.

The Goldilocks view means that each student must be given an amount of rigor that is just right for challenging them. Tasks and objectives must allow students to use skills they have mastered but also push them just beyond their current ability.

Moreover, Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (or ZPD) (1978) suggests that students engage in tasks that expose them to the perspectives and skill levels of other students to increase their own understanding. Scaffolding information in this way leads to an increase in knowledge and application development for all students involved.

Rigor by the Numbers: National Trends in Math and Science

There is a “clear link between the access, rigor, and intensity of high school coursework and success in college” (Posner, 2016). IDRA’s Ready Texas research report shows a mismatch between parents and schools regarding how well schools are informing students and parents about college pathways (Posner, 2016; also see Page 3).

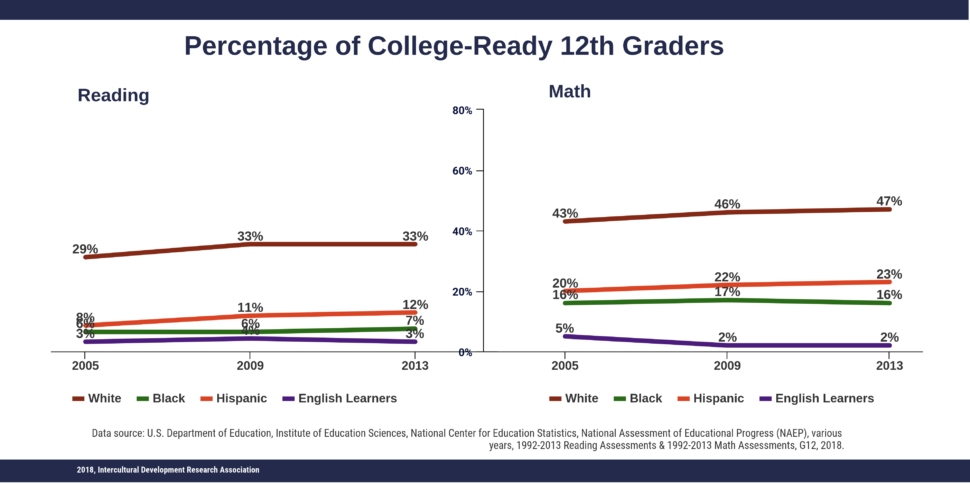

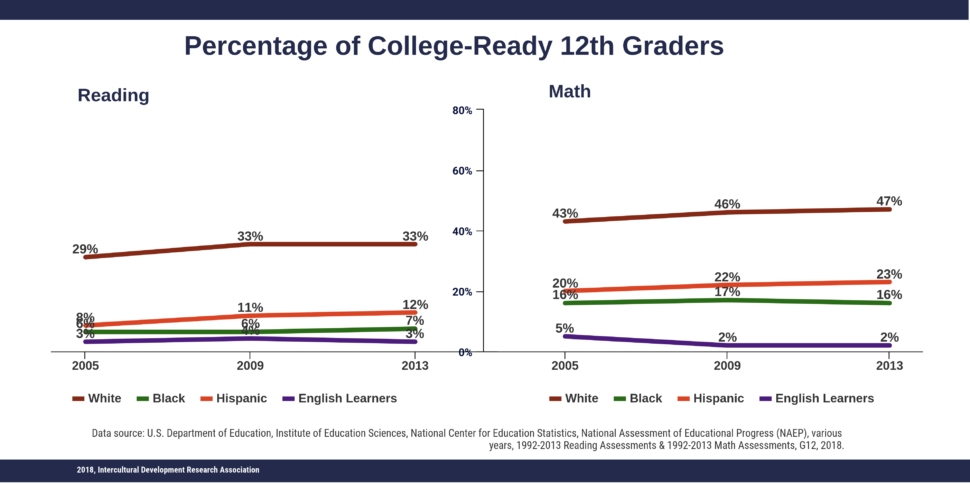

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) analyzed college preparedness rates from 1992 to 2013 for reading and math. The percent of students at or above college prepared has remained relatively consistently low (see graph at right) (2013). But with a growing population, the consistent rates affect more students over time.

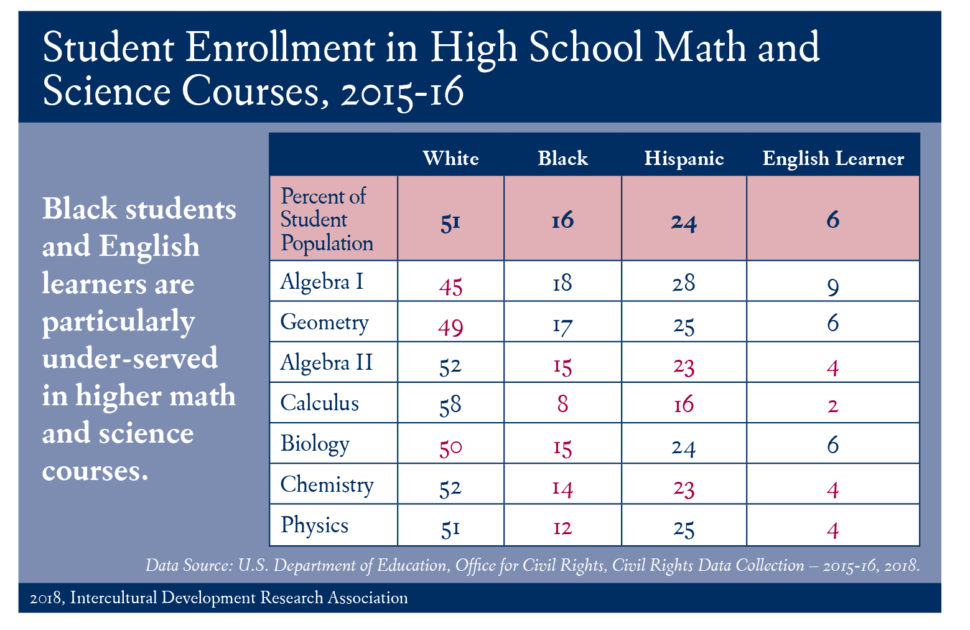

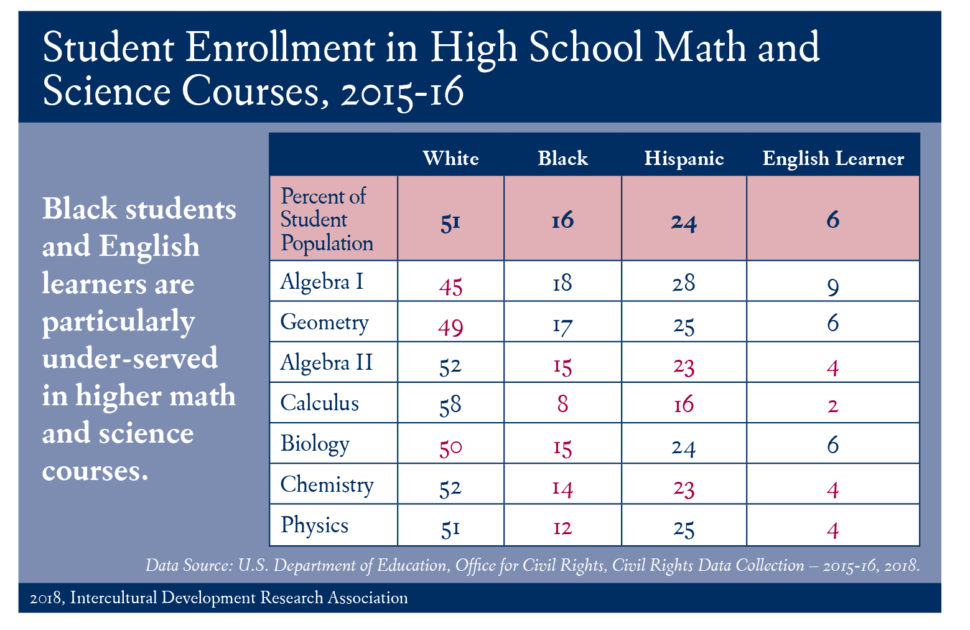

Of all ninth and 10th grade students in 2015-16 who were enrolled in Algebra I, 18 percent were Black and 28 percent were Latino, compared to 16 percent and 24 percent of high school enrollment, respectively (see table on Page 6) (U.S. Department of Education, 2018).

Listen to Classnotes Podcast episode: “Why Algebra II?”

Listen to Classnotes Podcast episode: “Higher Math for All”

White students, at 51 percent of high school enrollment, represented 45 percent of those enrolled in Algebra I. Black students and Latino students comprised lower rates of enrollment in other higher level courses. Black students represent 12 percent of students in physics and 8 percent in calculus. And Latino students represent 16 percent of students in calculus.

Over 963,000 English learner (EL) students were enrolled in high schools across the nation. Comprising 6 percent of all high school students, their enrollment rates in some courses were good: Algebra I, 9 percent; and geometry and biology, 6 percent. But their rates dropped in Algebra II, chemistry, and physics (4 percent) and in calculus and advanced mathematics (2 percent).

Increasing Access to Rigorous Coursework

The introduction of higher educational standards, including the Common Core initiative begun in 2010, pushed for higher academic student expectations. An increasing number of school districts across the nation are offering more STEM and advanced courses. But many lack diversity among the students taking them.

The latest Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) for 2015-16 shows that Black, Latino and English learner students are largely underrepresented in honors, advanced placement (AP), and higher-level math and science classes.

This disproportional engagement in rigorous studies could have root causes based in discriminatory practices, possibly making the lack of enrollment by diverse student groups a civil rights matter. Schools must address barriers that funnel students into tracking systems that do not encourage or prepare them for advanced coursework.

The IDRA EAC-South works with districts across an 11-state region and D.C. to promote equity for all students and address educational issues that prevent schools from ensuring equal opportunity for learning. We have provided technical assistance to several districts toward increasing the diversity of students taking upper-level courses with dramatic results.

There are many factors to consider when assessing educational opportunity, such as the relationship between teachers’ expectations of students of different racial/ethnic backgrounds and how that impacts campus disciplinary practices. Teachers’ implicit bias and lack of cultural competence can negatively impact students of color and ELs. Situations like this, place students’ academic, behavioral and social well-being at-risk.

“Rigor” Does Not Equal “College Ready”

College-ready students are those who are approved for, succeed in, and receive credit for on-level college courses leading to a degree, certificate or career without the need for remedial or developmental coursework (Conley, 2012).

The Four Keys to College and Career Readiness (Conley, 2012) outlines factors that are instrumental in improving student readiness for college and post-secondary success. The resource discusses attitudinal characteristics in addition to academic skills. Behaviors that are necessary for success in the workplace are sometimes taken for granted in high school and even college. These skills include self-discipline, ethical conduct, collaboration, initiation, motivation, initiative and resilience.

Promising Practices

It is important to prepare students for all the challenges college brings. Dr. Rogelio López provides a broad list of suggested services for students, parents and instructional staff with approaches that have been critical in maintaining a realistic college culture (López, 2010). Strategies include: hiring a dedicated counselor to assist students in preparing for college, ensuring true parent engagement, and providing professional development to increase teachers’ understanding of how to better prepare students for the academic rigors of college.

The Southern Education Foundation also encourages the following practices for school leaders. These approaches are especially helpful for students of color and students from immigrant families (Preston & Assalone, 2017).

Hold high expectations of all students. Research argues that rigorous instruction increases positive student engagement. Academic and behavioral supports create learning environments where every child has access to high-quality learning opportunities.

Actively invest in the recruitment and retention of highly qualified leaders and teachers committed to serving EL students and diverse student populations. Educators need advanced training and proper support to differentiate diverse learners’ needs from their academic knowledge and ability.

Begin preparing students for college in middle school. Students do better in high school when they have had access to a challenging curriculum in middle school.

Provide parents with sound college and financial aid information. Developing a plan to pay for college can begin as early as middle school.

Help students locate school programs that serve their needs. Students from low-income or immigrant families may need guidance in finding spaces that are successful in meeting the needs of a diverse student population.

Begin with the End in Mind

Developing a college-going mindset begins at a young age. Long-term student success needs long-range school supports. Provide students with multiple opportunities to find the academic habits that fit them just right!

Resources

Conley, D.T. (2012). A Complete Definition of College and Career Readiness (Eugene, Ore.: Educational Policy Improvement Center).

López, R. (June-July 2010). “All Students Deserve a Chance – Don’t Take It Away,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association).

Posner, L. (2016). “Ready Texas: Gathering Stakeholder Input to Guide Research on New Texas High School Graduation Plans,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association).

Preston, D., & Assalone, A.E. (2017). “5 Strategies for Creating College Readiness for Students of Color and Immigrant Students,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association).

Reich, G.A., Sevim, V., & Turner, A.B. (2015). Academic Rigor for All: A Research Report (Richmond, Va.: Metropolitan Educational Research Consortium, Virginia Commonwealth University).

Tienken, C.H. (2015). “Reconsidering Rigor,” Kappa Delta Pi Record, 51, 10-12.

U.S. Department of Education. (2018). 2015-16 Civil Rights Data Collection: STEM Course Taking (Washington, D.C.: Office for Civil Rights).

U.S. Department of Education. (2013). 2013 Mathematics and Reading Assessments, The Nation’s Report Card (Washington, D.C.: Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress).

Vygotsky, L.S., & Cole, M. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

Paula N. Johnson, M.A., is an IDRA education associate and is associate director of the IDRA EAC-South. Comments and questions may be directed to her via email at paula.johnson@idra.org.

[©2018, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the May 2018 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]