• by María Robledo Montecel, Ph.D. and Josie Danini Cortez, M.A. • IDRA Newsletter • February 2002 •

This is the last of a series of articles outlining major findings of IDRA’s research of exemplary and promising practices in bilingual education programs. It comes just as the U.S. Congress approves the 2001 Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) with the President signing the final HR 1 No Child Left Behind Act on January 8, 2002.

Education Law Changes

In this Act, Title VII (Bilingual Education Act) is now Title III (English Language Acquisition, Language Enhancement and Academic Achievement Act). The Office of Bilingual Education and Minority Languages Affairs (OBEMLA) is now named the Office of English Language Acquisition, Language Enhancement and Academic Achievement for LEP Students (OELALEAA). The National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education (NCBE) is now named the National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition and Language Instruction Educational Programs (NCELALIEP).

In the 120 pages of the new Title III regulations, the term bilingual education is never used. It has been replaced by English language acquisition.

The primary purpose of Title III is to “help ensure that children who are limited English proficient, including immigrant children and youth, attain English proficiency, develop high levels of academic attainment in English, and meet the same challenging state academic content and student academic achievement standards as all children are expected to meet” (Title III, Part A, Sec. 3102).

This primary purpose is similar to the original 1968 Bilingual Education Act, which states that limited-English-proficient (LEP) students will be educated to “meet the same rigorous standards for academic performance expected of all children and youth, including meeting challenging state content standards and challenging state student performance standards in academic areas.”

One key distinction is that the new regulation does not specify the methods for achieving such standards. The former law specified the development and implementation of exemplary bilingual education programs, development of bilingual skills and multicultural understanding, and development of English and the native language skills.

Through Title VII, exemplary bilingual education programs were developed and key research was conducted that informed and improved bilingual education programs for LEP students.

LEP Children Must be Served

Students who speak a language other than English have the right to comprehensible instruction that fosters learning. In 1973, the US Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the failure of schools to respond to the language characteristics of LEP children was a denial of equal educational opportunity (Lau vs. Nichols, 1973).

The Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974 states, “No state shall deny equal educational opportunity on account of his/her race, color, sex or national origin by… the failure of an educational agency to take appropriate action to overcome language barriers that impede equal participation by its students in its instructional program” (20 U.S.C., Section 1703 (f)).

This was followed in 1975 by detailed guidelines for determining the language characteristics of students and appropriate educational responses to those characteristics.

As the country enters this new legislative era, it must be remembered that the civil rights of children remain unchanged. Educators must use the most appropriate tools available to ensure their students’ success. One of these tools is bilingual education.

Thirty years of research have proven that bilingual education, when implemented well, is the best way to learn English. Children in such programs achieve high academic standards.

IDRA’s research re-affirms what is possible when committed and dedicated individuals use research to develop and provide excellent bilingual education programs for their students.

This last article presents IDRA’s major findings in the classroom level indicators, focusing on the program model, classroom climate, curriculum and instruction, teacher expectations, and program articulation.

At the Classroom Level

IDRA visited each of the 10 bilingual education programs selected for this study. It was important to collect information directly from each program and observe first-hand the program models being implemented. This was in addition to the extensive review of quantitative student outcome and school data, and surveys of principals, teachers and administrators.

IDRA researchers conducted structured, formal classroom observations as well as structured interviews with the principals and central office administrators and, whenever possible, focus group interviews with teachers, parents and students. Researchers also described each site visit providing a rich context for each program.

Program Model

In the schools IDRA studied, all of the program models – transitional, late exit and dual language – were grounded in sound theory and best practices associated with an enriched, not remedial, instructional model and were consistent with the characteristics of the LEP student population. Administrators and teachers we surveyed believed in the program and consistently articulated on its viability and success.

An IDRA researcher observed at one school: “Before starting the bilingual program four years ago, the staff read the literature and visited exemplary schools in Oregon and around the country. It then decided to implement a late exit model. Last year, they asked a team [of researchers] to the school to assess the program and provide the staff with suggestions for improvement.”

At another school, a teacher stated: “We don’t have an early exit model. Students gradually transition. We work hard to make sure we teach concepts that will help them transition. They have content and concepts in their own language that help them be successful.”

Classroom Climate

The classrooms we studied strongly reflected the school climate. There were different styles but common intrinsic characteristics, such as:

- high expectations for all students,

- recognition and honoring of cultural and linguistic differences,

- students as active participants in their own education,

- parents and community members actively involved in the classrooms through tutoring, sharing experiences, reading, planning activities, etc., and

- heterogeneous grouping.

People we surveyed reported highly interactive and engaging classroom climates with a high percentage of time on task and consistent, positive student behavior.

An IDRA researcher noted: “For the most part, few of the classrooms were arranged with desks. If the classroom had desks, they were arranged in such a way that they made a table or a center for the group to work with. The students had very interesting discussions on different topics. The students are responsible for setting up the classroom. They set up the bulletin boards, and they decide or give input into the type of direction they want their discussions to follow.”

A Russian parent stated, “[The teachers] are really passionate about teaching our kids.”

Curriculum and Instruction

In the schools IDRA studied, the curricula were planned to reflect the students’ culture. All of the instruction we observed in the classrooms was meaningful, academically challenging, and linguistically and culturally relevant. Teachers used a variety of strategies and techniques, including technology, that responded to different learning styles.

Teachers and administrators reported their bilingual program was designed to meet the students’ needs with alignment between the curriculum standards, assessments and professional development. Teachers were actively involved in curriculum planning and met regularly, with administrative support, to plan.

At one school, an IDRA researcher reported: “Students start and finish in a mainstream classroom. The first and last periods of the day students are with the same teacher and their mainstream class. This gives the students a feeling of being core integrated into the entire school. This is different from other programs where ESL [English as a second language] students only are integrated during P.E., art and music.”

At another school, a researcher noted: “There is a day set aside for teachers to plan Russian and Spanish classes and to make sure they are in their native language but along the same theme. So all children are getting the same thing in their native language.”

Teacher Expectations

Teachers expected all students to succeed and were willing to do whatever it took to reach this goal. They valued diversity and drew on its strengths, creating an environment in the classroom and the school that was accepting, valuing and inclusive.

Teachers and administrators also reported a high commitment to their students’ educational success and cited this as a critical factor in academic achievement.

An IDRA researcher observed at one school: “All teachers are truly committed to preparing the students for high performance… Students are very aware that as they learn English, they need to follow certain paths that will lead them to college.”

A teacher stated: “During training, we learn about not watering down the curriculum. We expect the same things for all students.”

An observer reported: “I tried to press them [teachers and staff] to talk to me about ‘problem students,’ and no one saw any student as such.”

Program Articulation

There were common programs of instruction across grade levels that had been aligned with developmentally appropriate practices and student language proficiency levels in English and the students’ native language. This was accomplished in many schools through coordination and communication and through strong linkages across all levels (grades, principal and faculty, school and central office).

Teachers met frequently to plan collaboratively. This open and frequent communication, coupled with alignment across the curriculum and assessment resulted in a seamless, well-articulated curricular and instructional plan.

A teacher stated: “Action research [allowed us to look at] how we could bring our ESL and bilingual education students up to the level of all students. We collected state test data and found that not all students who fell through the cracks were ESL students but were actually Title I students. This resulted in grouping students and giving them additional support.”

At another school, an IDRA researcher observed: “There appears to be a great deal of coordination in the school. Teachers talk about ‘good’ faculty meetings that help them continue their mission. I thought this was quite unique – teachers actually praising faculty meetings.”

Key Criteria

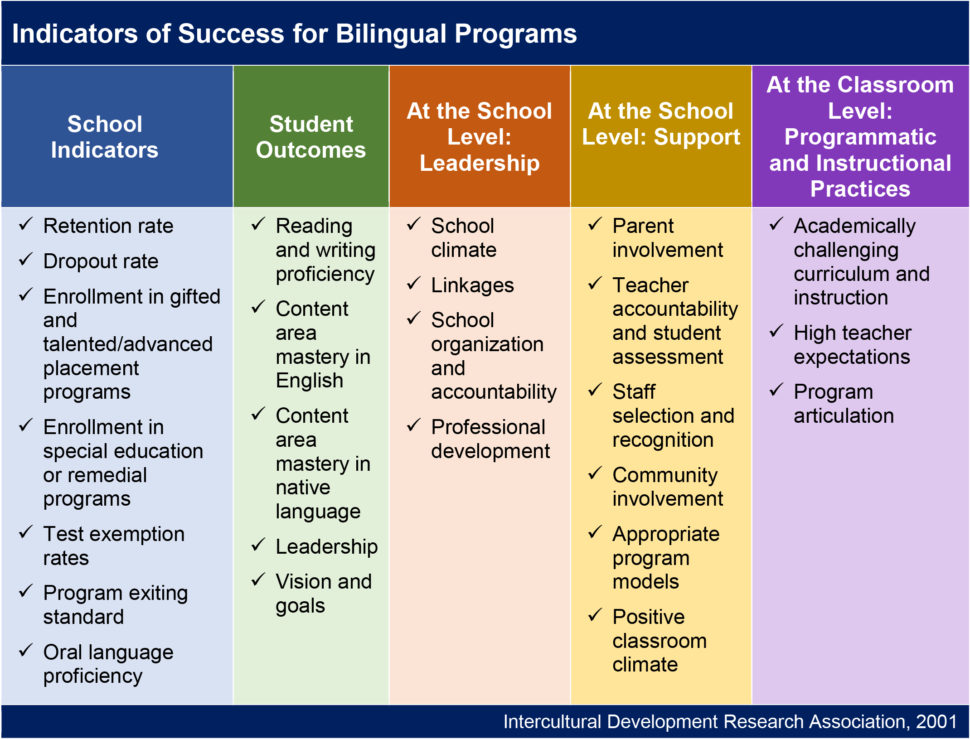

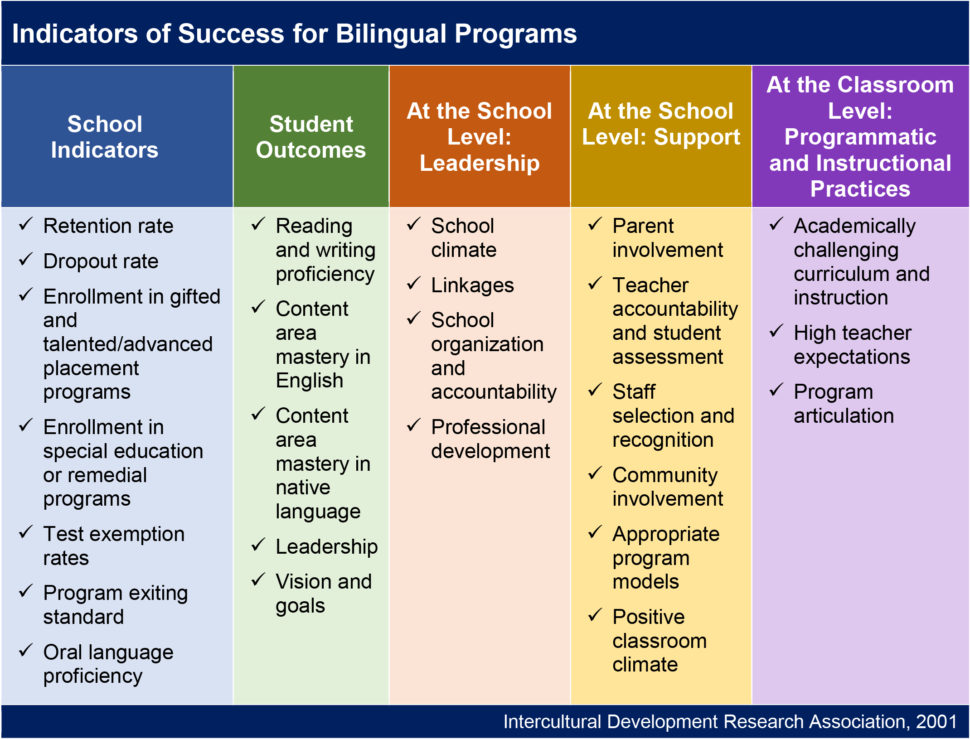

IDRA’s study resulted in a set of criteria for identifying promising and exemplary practices in bilingual education. At the classroom level, programmatic and instructional practices included the following.

Program Model

Teachers and community members participate in the selection and design of a bilingual/ESL program model that is consistent with the characteristics of the LEP student population. The program model is grounded in sound theory and best practices associated with an enriched, not remedial, instructional model. Administrators and teachers believe in the program, are well versed on the program, are able to articulate and comment on its viability and success, and demonstrate their belief.

Classroom Climate

The classroom environment communicates high expectations for all students, including LEP students. Teachers seek ways to value cultural and linguistic differences and fully integrate them into the curriculum.

Curriculum and Instruction

The curriculum reflects and values the students’ culture. The curriculum adheres to high standards. Instruction is meaningful, technologically appropriate, academically challenging, and linguistically and culturally relevant. It is innovative and uses a variety of techniques that respond to different learning styles.

Teacher Expectations

Teachers expect all students, including LEP students, to achieve at high standards and are willing to do whatever it takes to reach this goal. They value diversity and know how to create an environment that is accepting and inclusive.

Program Articulation

There is strong evidence of a common program of instruction that is properly scoped, sequenced and articulated across grade levels and has been aligned with developmentally appropriate practices and student language proficiency levels in English and the students’ first language.

Example of a Successful Bilingual Program

The above are five of the indicators that IDRA found in the research sites. They comprise the final of five dimensions for assessing a school’s success in educating English-language learners:

- School indicators,

- Student outcomes,

- Leadership,

- Support, and

- Programmatic and instructional practices.

One example of such a successful program is found at River Glen Elementary School in San José, California.

River Glen Elementary School, San José, California

River Glen Elementary School (kindergarten through grade six) is a public school of choice – parents apply and students are selected through a lottery process. Students in kindergarten, first and second grades are taught completely in Spanish.

All students receive increased amounts of English instruction each school year so that by the fifth grade, students spend half of their day in Spanish instruction and the other half in English instruction. At the end of the fifth grade, students understand, speak, read and write in both Spanish and English and meet high academic standards in all subjects.

River Glen Elementary School is a public school of choice in another way – the principal and staff chose to promote and nurture bilingualism despite California’s Proposition 227, which ended bilingual education instruction in most of the state’s schools. River Glen Elementary School applied for and received a waiver to continue its two-way bilingual immersion program despite the anti-bilingual sentiment in the state.

The program’s goals are to:

- promote high levels of oral language proficiency and literacy in both Spanish and English,

- establish a strong academic base in two languages, and

- develop cross-cultural understanding between students.

The program has been granted exemplary status by the state of California.

The school’s underlying philosophy for its program design is valuing bilingualism and the benefits accrued. The program is designed so that strong emphasis on Spanish instruction in the early grades benefits both English and Spanish language groups.

For Spanish-language speakers, this early emphasis on their home language enables them to “expand their vocabulary and build literacy in their first language; study a highly academic curriculum in their first language; successfully transfer Spanish reading and writing skills to English in later grades; acquire high levels of self-esteem by becoming bilingual and playing a supportive role for their English-speaking classmates.”

English-language speakers benefit from “extensive exposure to Spanish, accelerating their absorption and usage of the language to achieve early Spanish literacy; a highly academic curriculum, taught in a second language; the ability to transfer Spanish reading and writing skills to English language reading and writing after the second grade; the confidence to speak Spanish, resulting from the self-esteem and pride they gain because they are bilingual.”

During the school site visit, the IDRA researcher noted a very positive school climate. The principal and teachers were proud of their work, and it showed. As a matter of course, the school is opened to visitors once a month.

The school building was clean and attractively decorated. All of the information posted around the school was in Spanish and English. Everyone was friendly and made visitors feel welcome and comfortable. The friendliness and collegiality among staff was also evident. Parents, teachers and staff assistants were very comfortable with each other.

Many of the classrooms had about 30 students with a teacher and assistant in each classroom.

In one classroom, students debated the pros and cons of living longer than normal. In another, students discussed whether or not they would take it if they had the opportunity to make more money.

Students are provided with challenging course materials in both English and Spanish. Teachers use only Spanish or English during instruction. They do not translate but instead use other second language acquisition techniques and strategies to make the language and content understandable.

Teachers also exchange classes with each other at the kindergarten through second grade levels during the English portion of the day so that students learn to identify a particular teacher with a particular language, increasing the likelihood they will use the specific language in particular contexts.

Teachers provide direction and counsel to their students but always allow for student input and ownership.

The bilingual program is an integral part of the school. All of the teachers are expected to speak Spanish fluently. The IDRA observer reported: “‘Proud to be Bilingual’ should be the key phrase to describe River Glen Elementary School. Everyone there, from the teachers to the parents, recognize that bilingualism is a valuable asset. They are very proud of their stance on bilingual education, despite the state’s controversial Proposition 227.”

River Glen Elementary School teachers have courageously defended their advocacy of bilingual education despite opposition from the state, from many community members and from their own teacher union.

Every classroom has a computer that students use throughout the day. The computer software in kindergarten through second grade is in Spanish. Students in the upper grades have a choice of the mode and language of instruction.

Teachers at River Glen Elementary School must be certified in bilingual education. There is very little turnover at the school.

All of the teachers commented on the high level of good and open communication with each other and with their principal. They usually meet on a weekly basis to plan, always focusing on instruction. The principal and teachers implement a structured curriculum where every teacher at every grade level knows exactly what is expected of them. This approach allows for any new teachers to become acclimated to the school and receive the necessary information and support.

Teachers usually participate in staff development at the beginning of each year. The focus of the last sessions was the issue of standards. School district and state academic standards are met or exceeded at each grade level.

All of the teachers have high expectations for their students. Students are expected to achieve at or above the state standards.

One teacher said: “We have our high expectations, but it is our colleagues who are pushing us to maintain and stay focused. I know if I lag behind, the teacher next year will come and talk to me and see what it is I am teaching.”

Student performance is assessed in a variety of ways from timed tests to portfolios to folders that students keep at their desks. They also hold themselves accountable for the success of each and every student.

During the classroom observations, IDRA representatives reported that each teacher knew the exact status (task and skill level) of every student. Student progress was constantly monitored with the teachers in the lower grades keeping a running record of the student’s progress. In the upper grades, almost all of the student work was posted on walls or displayed in some form.

Family involvement is an important contributor to the program’s success. While parents are not necessarily bilingual, they must be supportive of bilingualism. They must also be willing to make a long-term commitment to the program to allow enough time for their children to succeed.

The IDRA researcher reported: “The school is successful because of the commitment and integrity that the teachers have toward the bilingual program at their school. They attribute their success to the clear and focused program that is articulated throughout the campus and to the support that the principal provides.”

How I Am

One student at River Glen Elementary School wrote the following poem illustrating the sentiment found throughout this program and the recognition and celebration of culture, ethnicity and languages.

En el espejo

cuando me miro

en el espejo

como me gusta

asi como soy.Soy morenito

Me falta un diente

Y toda la gente

Me dice chulito.Como me gusta

Como me gusta

Como me gusta

asi como soy.

In the mirror

when I see myself

in the mirror

how I like

how I am.I’m dark-skinned

I’m missing a tooth

And everyone

Calls me cute.How I like

How I like

How I like

How I am.

Resources

River Glen Elementary School. “Project Two-Way, Title VII Academic Excellence Project, River Glen Elementary School Two-way Bilingual Immersion Program, Literacy in Two Languages,” informational brochure (San José, California: River Glen Elementary School, nd).

Robledo Montecel, M., and J.D. Cortez. “Successful Bilingual Education Programs: Indicators of Success at the School Level,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, November-December 2001).

Robledo Montecel, M., and J.D. Cortez. “Successful Bilingual Education Programs: Indicators of Success at the School Level Part II,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, January 2002).

Robledo Montecel, M., and J.D. Cortez. “Successful Bilingual Education Programs: Criteria for Exemplary Practices in Bilingual Education,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, August 2001).

Robledo Montecel, M., and J.D. Cortez. “Successful Bilingual Education Programs: Student Assessment and Outcomes,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, October 2001).

Robledo Montecel, M., and J.D. Cortez. “Successful Bilingual Education Programs: 10 Schools Serve as Models,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, September 2001).

María Robledo Montecel, Ph.D., is the IDRA executive director. Josie Danini Cortez, M.A., is the IDRA production development coordinator. Comments and questions may be directed to them via e-mail at feedback@idra.org.

[©2002, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the February 2002 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]