• by María Robledo Montecel, Ph.D. and Josie Danini Cortez, M.A. • IDRA Newsletter • September 2001 •

Editor’s Note: Last year, the Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) conducted a research study with funding by the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Bilingual Education and Minority Languages Affairs (OBEMLA) to identify characteristics that contribute to the high academic performance of students served by bilingual education programs. The August 2001 issue of the IDRA Newsletter began a series of six articles describing this research study’s significant findings. The first installment provided an overview of the research design and methods. This second article features an overview of the schools’ demographics and the major findings pertaining to school indicators.

While there are many such schools and classrooms across this country, time and resources dictated that IDRA work with only 10 schools and use their lessons learned as a guide for developing criteria that others can use to assess their own programs. The following provides an overview of these schools’ demographics and the major findings pertaining to school indicators. There is also a profile of one of the schools as described by an IDRA researcher.

School Demographics

By design, the school demographics reflected a diverse landscape. Programs in eight elementary schools, one high school and one middle school participated in this research study. The student enrollment for the 10 schools ranged from 219 in the high school to 1,848 students in the middle school. By geographic location, there were six urban schools, three rural schools, and one reservation school.

There was also diversity in ethnic representation. Hispanic students ranged from 40 percent to 98 percent of students enrolled; Asian students made up 2 percent to 41 percent of the students enrolled; Russian students ranged from 12 percent to 32 percent of the students enrolled; and Native American students comprised 3 percent to 98 percent of the students enrolled. The number of limited-English-proficient (LEP) students ranged from 20 percent to 100 percent. Four of the 10 schools implemented dual language or two-way bilingual programs. The languages used for content area subjects included Spanish, English, Russian, and Navajo.

All of the schools were committed to maintaining the students’ primary language and culture while learning English. This commitment was evident in the school administration and staff, the majority of whom were proficient in two languages. Most of the office staff also were bilingual, allowing for open communication between the school personnel and the students and families.

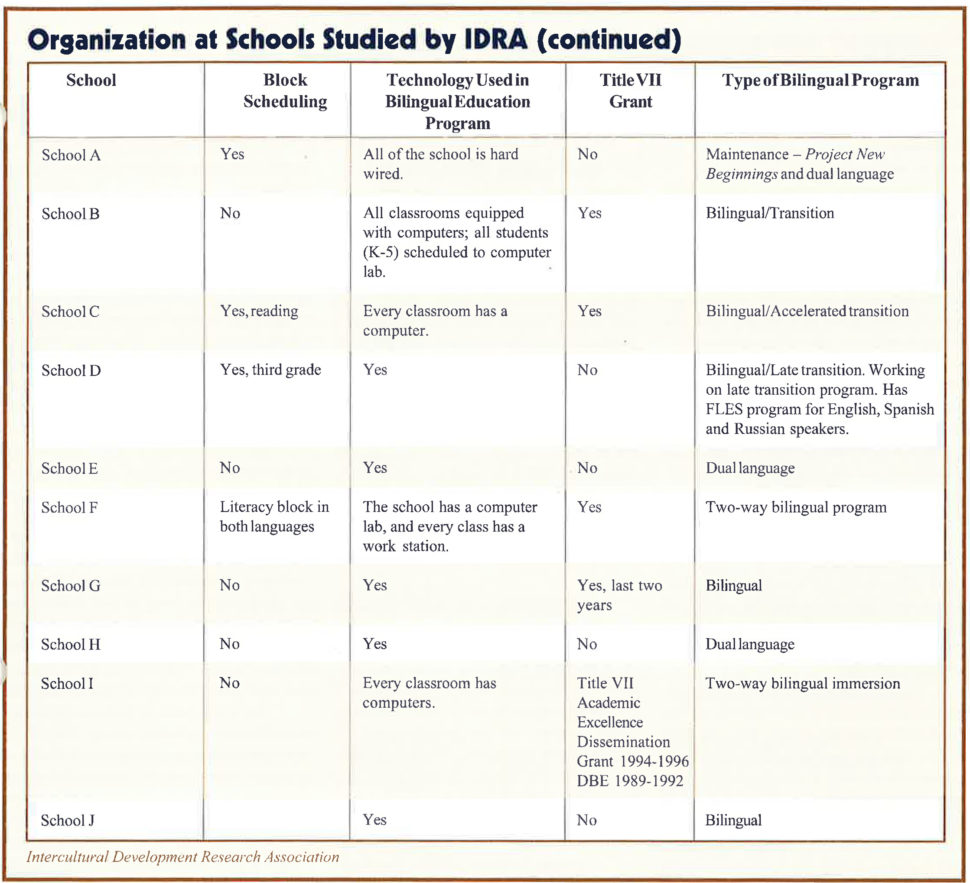

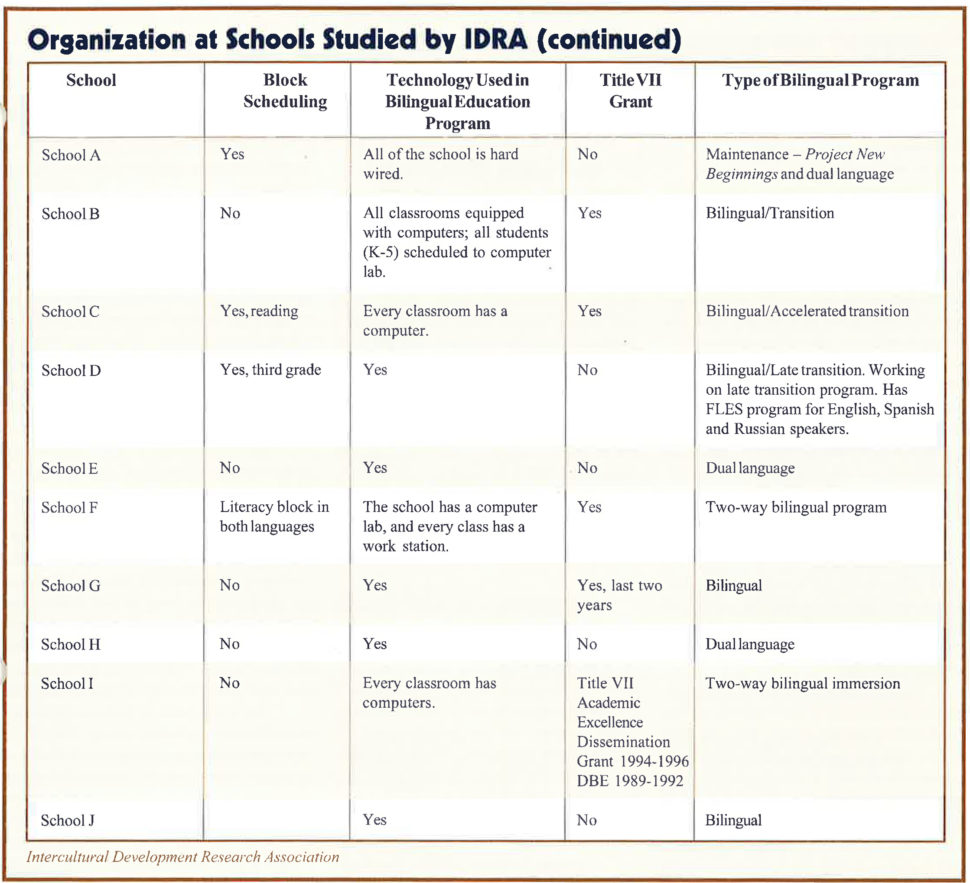

Five of the 10 schools had Title VII funds, including one in California, that had received an Academic Excellence Dissemination grant in 1994 to 1996.

School Organization

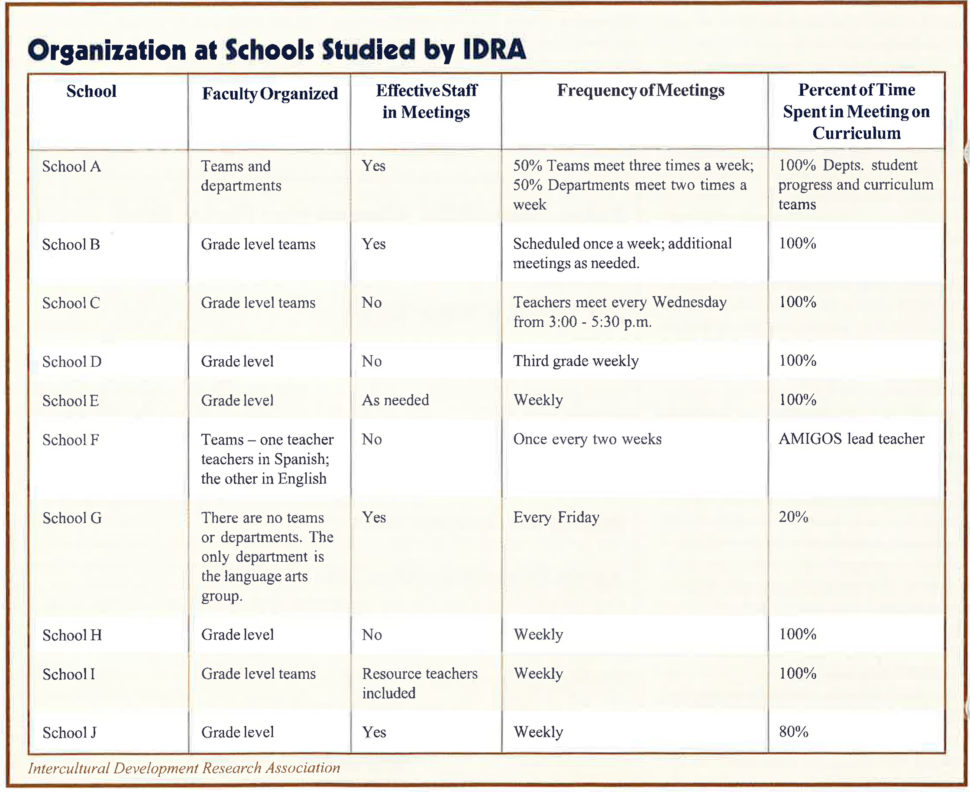

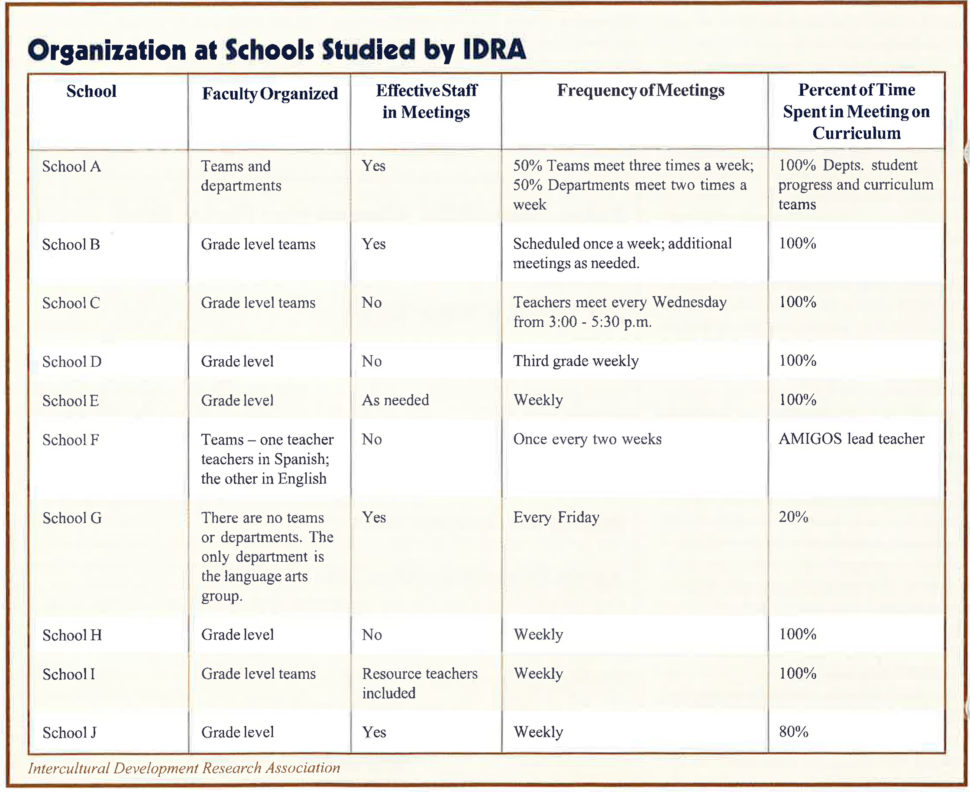

Schools generally organized themselves by grade level teams with both vertical and horizontal alignment and accountability evident. Faculty met frequently, some as often as three times a week. There was support by the administration for these regularly scheduled meetings, with the principals often planning the agendas, in most cases, with input from the teachers and staff.

Six out of the 10 schools included elective staff in their meetings, allowing for easier integration and alignment. Most of the time at the meetings was spent on curriculum and instruction, with staff using student data to inform curriculum and instruction decisions. Teachers were also provided regular planning time.

There was open and easy communication between the principals and teachers at these schools. Teachers reported frequent discussions with their principals via e-mail, meetings (formal and informal), open-door policies, and principals visiting the classrooms daily.

All of the schools had technology in classrooms. The extent of use varied by school (see boxes below).

School Indicators

The 10 schools participating in this study had similar profiles, including:

- High poverty – Nine of the 10 schools had at least half of their students eligible for the free or reduced-price lunch program, a poverty indicator.

- High average attendance – All of the schools had high attendance (86 to 98 percent).

- High percentage of their students participating in the bilingual education programs – Most of the schools had at least one-third of their enrolled students being served by bilingual education programs – one school served all of its 219 enrolled students.

- Low retention rate – Most of the schools had low retention rates. Four schools retained 1 percent or less of their students.

- Low annual dropout rate – Nine of the 10 schools had a 0 percent annual dropout rate.

- Low percentage of migrant students – More than half of the schools did not serve migrant students. Of the five that did, three served less than 10 percent. However, in one school, two out of five students were migrant. 03

- LEP student representation in gifted and talented programs – Most of the schools with gifted and talented or advanced placement programs had LEP students fully participating.

- Low LEP student representation in special education programs – Most of the schools had few LEP students in their special education programs.

Example of a Successful Bilingual Education Program

Each bilingual education program is part of a school with its own unique context and special characteristics that are clearly evident. These characteristics or “indicators of success” are described in the following profile of one school, providing a firsthand look at the inner workings of a successful program and school.

Heritage Elementary School, Woodburn, Oregon

Woodburn, Oregon, billed as the “City of Unity,” prides itself on its cultural diversity. Here, Anglos, Hispanics and Russians come together in a unique blend of local and extended heritage. Woodburn has developed a cosmopolitan blend of cultures not normally found in cities of its size – an area of only four square miles.

Woodburn is located in northeast Oregon, approximately halfway between Salem and Portland, in the midst of lush, fertile farmland. Employment opportunities range from food processing to construction of manufactured housing to professional services, resulting in a relatively affluent community. Historically, farming has contributed greatly to Woodburn’s economic health, and large farms and orchards still put their stamp on this area.

Heritage Elementary School is an attractively designed new school, only three years old, and stands in a neighborhood of well kept middle- to upper-class homes. It is adjacent to the middle school.

The school serves three language groups: Hispanic Spanish-speakers, Russian-speakers and English-speakers. Hispanic students are predominately of Mexican or Mexican-American origin, and most are classified as migrants because their parents are local farmworkers (having moved to Woodburn from Texas or California) who sometimes go north to Washington to pick fruit. Many workers have begun to settle in Woodburn and are no longer classified as migrants, but new migrant farmworkers continue to replace those who have been reclassified.

Most of the Russian students are recent immigrants and are members of a sect known as Old Believers, which was formed more than 700 years ago when the Russian Orthodox church split from the Greek Orthodox church. Portions of the sect spent many years in exile in China, Turkey and Argentina before coming to Woodburn to settle in the 1950s. They speak an old dialect of Russian and follow many traditional customs that separate them from mainstream American society. Also, many are migrant workers in the fishing and timber industries who migrate to and from Alaska.

The Heritage Elementary School building is clean and bright. Pictures of parents, teachers and students as well as examples of students’ work decorate the hallways. When IDRA researchers visited, the principal exhibited her pride both in the teachers and students. She spoke very openly about the program and its continual development.

A third grade teacher believes the building is one of the best support services available for students learning English. She remarked, “We label everything on the walls in Russian, Spanish and English – hallways, classrooms and administrative offices.”

Inside the classrooms, posters and student work grace the walls. Most of these use both English and another language. There are also a large number of books in every classroom, both in the native language and English. In one class, there are more than 40 books that have been translated from English to Russian by a group of involved parents.

Most classrooms have listening centers, a reading corner and a computer station. Student desks are arranged in groups of four or five, and the teacher moves among the groups. Moreover, teachers interact with each other frequently regarding instructional topics and methods.

One teacher cited the sharing of ideas and thoughts among the staff as being the most important professional development activity. “Curriculum planning and mapping here at the school helps us to see that we are all going in the same direction,” she said.

Students are enthusiastic and participate in the lessons, some teacher-directed and others independent. Although teachers encourage the students to speak in their home language during the morning sessions, they are not prohibited from communicating in English if they want to. Thus, students can often be heard conversing in both English and their home language.

Heritage Elementary School conducts several bilingual education programs simultaneously. The late-exit program serves 342 English-learners (57 percent) from kindergarten through third grade who had low English student language assessment scores when they entered school. Even though these students will officially exit the program at the end of the third grade, the plan allows for all of them to continue in a bilingual program through fifth grade. The program was begun four years ago and has added a grade each year, having reached third grade this year.

Students with higher English language assessment scores upon initial entry are placed in mainstream classrooms and can be pulled out of class for English as a second language (ESL) support in grades two through five. In grades four and five students can receive pull-out native language support or support from bilingual educational assistants within the mainstream classrooms.

Until recently, Oregon did not require that bilingual teachers obtain a bilingual endorsement; nevertheless, five teachers from Heritage Elementary School are currently working toward one. Of the total staff, 35 percent speak Spanish and 19 percent speak Russian. Of the classified staff, 50 percent speak Spanish and 29 percent speak Russian. Of the three native language classrooms observed (one Russian and two Spanish), all three teachers and one aide were fluent in the respective language.

Heritage Elementary School has drawn on the research of prominent bilingual educators in designing and evaluating its program. Before starting the program four years ago, the staff read the literature and visited schools with exemplary practices in Oregon and around the country. They then decided to implement a late-exit model. Last year, they asked a research team to the school to assess the program and provide the staff with suggestions for improvement.

The school has both a Spanish-English bilingual and a Russian-English bilingual program. In addition, for English proficient students, it offers Spanish and Russian as a foreign language for an average of 90 minutes per week.

The design of the bilingual program specifies the amount of time devoted to each of the three components: an ESL component called English language development, instruction in the native language, and sheltered English techniques. Initial reading instruction is provided in the native language, with English literacy usually delayed until third grade. The content areas are provided initially in the native language with a carefully planned introduction into each grade of specified subjects using sheltered English techniques.

From the beginning of the program at the kindergarten level, students spend a portion of each day with English speakers. Russian and Spanish speakers are also grouped together for English language development. The staff reported that this accelerated their English acquisition because both kinds of students were forced to use English to communicate with each other. Students remain in the program through at least the fifth grade.

IDRA researchers noted that all the instruction is uniformly of high quality and reflects best practices recommended for mainstream and second language-learners. Students often work in cooperative, heterogeneous groups or with partners. Student-to-student and teacher-to-student interactions are frequent, meaningful and focused on instructional tasks. Activities are hands-on, and teachers use a large variety of materials: bilingual books of many genres and types as well as visual, audiovisual and art materials.

Many students were observed receiving individual or small group assistance from additional teachers, bilingual educational assistants and parents. This extra help is provided inside their classrooms or in quiet, cozy corners in the halls outside.

All students, English-learners and native English-speakers, are integrated in one of the morning and afternoon homerooms. This gives everyone an opportunity to mix with each other as a group and begin and end each day together.

One teacher interviewed believes this arrangement has contributed to the success of the school’s program. She noted: “Students start and finish in a mainstream classroom. The first and last periods of the day, students are with the same teacher and their mainstream class. This gives students a feeling of being more integrated into the entire school.”

Throughout the day, English-learners are divided into language groups and placed in an ETP instructional model (late-exit, early-exit, literacy center, or mainstream classroom depending on each student’s language capability) and are taught in their native language of Russian or Spanish.

Language capability is assessed by administering a home language survey. The ETP coordinator makes the appropriate assessment to determine the particular English learning level of each child. Students are also given the Oregon student language assessment and the Woodcock-Muñoz language tests before being placed in an instructional model. Additionally, kindergarten and first grade students are given the Brigance Screen to measure basic language skills, and teachers use various classroom assessment methods to determine how students are progressing during the year.

Although the school is moving toward a late-exit program, presently only those in kindergarten through second grade are in such a program. Third, fourth and fifth graders are in an early-exit program, having made the transition into English. Other students are identified as mainstream English, and some students are placed in literacy centers. Sheltered English techniques are used to help students who have not mastered English by the end of fifth grade.

The school also has an English Plus program, through which parents can opt to have their children continue to learn their native language. Students can also learn a third language through English Plus – English, Spanish or Russian.

Heritage Elementary School’s bilingual education practices are deemed exemplary in large part because of its support of native language development and retention. According to a Russian parent: “Many students have grandparents who don’t speak English. The kids are very interested in speaking to their grandparents, so they are motivated to learn. The children are not embarrassed to speak Russian in school, because they use it at home and in their neighborhood.”

This integration of community culture and school lifestyle makes an enormous impression on the parents and stimulates them to contribute to their children’s school and become involved in their children’s success.

Although the state of Oregon requires that by third grade students are transitioned to English, the school continues to create avenues for supporting the students in their native language while they learn English.

Also important is the staff’s organization of the classwork for these students, such as in the English language development classes, where students who are native Spanish-speakers are mixed with native Russian-speakers. A Russian parent affirmed the effectiveness of this arrangement: “Half of the Spanish class and half the Russian class are intermingled where they must learn English.”

Also vital to this school’s success is the high level of involvement of parents, despite many of them leading migrant lifestyles. Russian and Hispanic parents state that volunteering is second in importance only to the teachers’ involvement in assuring the success of the bilingual program.

Heritage Elementary School exhibits three of the most important elements of successful bilingual education practices: (1) a dedication to providing the most successful learning and development programs to the students; (2) teachers and staff who truly care about the students and are passionate about teaching, and (3) parents who become involved and volunteer in educational activities.

Organization at Schools Studied by IDRA

María Robledo Montecel, Ph.D., is the IDRA executive director. Josie Danini Cortez, M.A., is the production development coordinator. Comments and questions may be directed to her via e-mail at feedback@idra.org.

[©2003, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the September 2001 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]