Testimony of IDRA presented for the Senate Education Committee, April 4, 2018. Presented by David Hinojosa, National Director of Policy

Chairman Taylor and Members of the Committee:

Thank you for allowing the Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) the opportunity to provide written testimony of its research and analysis on improving high quality educational opportunities for all Texas students. Founded in 1973, IDRA is an independent, non-profit organization that is dedicated to assuring equal educational opportunity for every child through strong public schools that prepare all students to access and succeed in college. Throughout its history, IDRA has conducted extensive research and analysis on a range of Texas and national educational issues impacting public school children, including school finance, school integration and school privatization options.

Based on its review of the research, IDRA recommends that the Texas Legislature:

1. Improve its support for building strong public schools by providing greater equitable educational opportunities for all students across the state;

2. Expand true parent choice and opportunity by considering a proposal for racially and economically diverse, district-operated charter schools that aim to ensure high quality, equal educational opportunities in a diverse learning environment.

3. Avoid expanding school privatization options, including privately-operated charter schools, vouchers and neo-vouchers, such as tax credits and opportunity tax scholarships, which research shows: (1) fail to deliver on the promise of better learning opportunities and student performance; (2) siphon limited resources from local community schools; (3) open up the potential for violating students’ civil rights; (4) hinder transparency and accountability; and (5) tend to lead to more schools being racially segregated.

A Roadmap to Equity: Creating Meaningful Educational Opportunity for All

Strong, recent research shows that increased funding has contributed to both improved student performance and lifetime outcomes, especially for underserved students (Jackson, 2016; Lafortune, 2016). Yes, money matters, and how that money is spent and on which children, also matters. Below is a research- and equity-based model that states can follow to ensure that all children access the meaningful educational opportunities they need to succeed in school and in life.

Texas is Off-track

Texas has established foundation standards and goals for all Texas schoolchildren, though some may need revisiting under the new graduation endorsement scheme as some students may not be prepared to go to college upon graduation. Texas also has identified several essential building blocks, though many are not set based on actual or estimated costs of today. However, Texas goes off-track from the Roadmap to Equity in most other areas:

- Texas fails to adopt strong principles of equity and meaningful opportunities to learn, and instead allows students’ zip codes to determine their quality of education;

- Texas fails to identify fair, stable revenue resources, and instead continues to rely on largely disparate property taxes while cutting other taxes;

- Texas fails to estimate costs of educational programs and services based on research, and instead relies on outdated, arbitrary weights, for example;

- Texas fails to equitably distribute funds to low- and mid-wealth school districts, and instead extends much greater opportunities to the students attending high-wealth school districts;

- Texas does not effectively monitor the distribution of funding, educational opportunities and expenditures to ensure students generating the funding access an excellent education in the classroom, and instead allows, for example, nearly 50 percent of funds for compensatory and bilingual education to be spent for other purposes;

- Texas fails to meaningfully review and revise its school finance system based on input from inclusive stakeholders, and instead relies on politicking and prior year revenues to dictate educational opportunity;

- Texas fails to ensure meaningful access and opportunity for all schoolchildren and instead ensures a system that perpetuates a dual system between the haves and the have-nots.

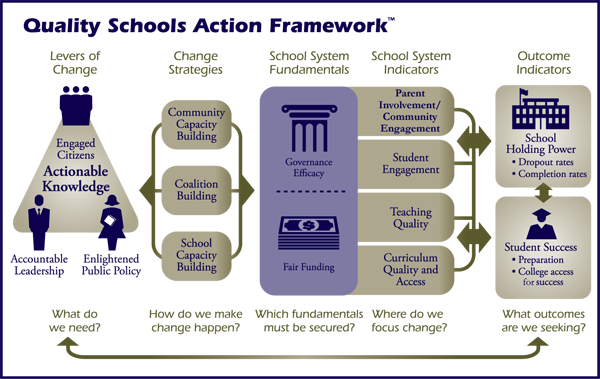

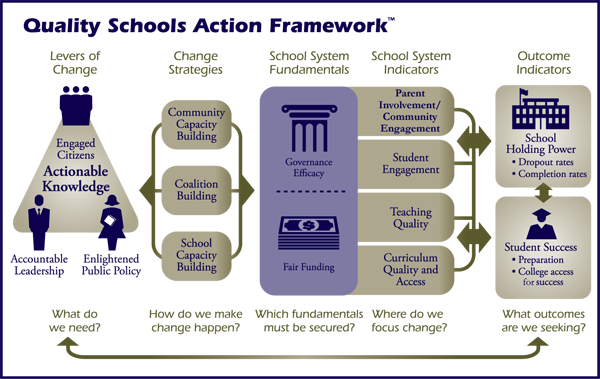

IDRA Quality School Action Framework: Building Excellent Schools

School finance is one incredibly important part of building excellent schools for all students. However, several other indicators, strategies and levers of chance also support equitable educational opportunity. Below is the Quality Schools Action Framework™ developed by IDRA (Robledo Montecel & Goodman, 2010) that may assist the Legislature in drafting future laws that could help the state achieve its public education mission of “ensuring that all Texas children have access to a quality education that enables them to achieve their potential and fully participate now and in the future in the social, economic, and educational opportunities of our state and nation” (Texas Education Code § 4.001).

Intercultural Development Research Association

A Modest Proposal:Racially and Economically Diverse District-Charter Schools

Rather than looking at efforts to increase the presence of privately-operated charters – even “successful” charters – the Legislature should look at the whole picture of what it takes to make great schools for all schoolchildren. Continuing to legislate according to the special interests’ latest reform measures has not yielded the results necessary – especially for students of color and low-income, at-risk and English learner children.

One example of a promising approach for the Senate to consider is legislation that would support the creation of diverse school district charter schools that integrate students along racial and economic lines in a college-going environment. These schools would capture the original intent of charter schools in 1998, which was to encourage local school districts to experiment with innovative ways of reaching students and to help “reinvigorate the twin promises of American public education: to promote social mobility for working-class children and social cohesion among America’s increasingly diverse populations” (Kahlenberg & Potter, 2014).

Texas could be a national leader in supporting these innovative schools and it could not come at a better time with race relations suffering across the nation and schools experiencing severe racial segregation. Furthermore, the academic performance of students would not be compromised as integrated schools have been found to benefit both minority and White students academically, socially and emotionally (Seigel-Hawley, 2012). And these schools could be created without running afoul of the Constitution (Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1; Ali & Perez, Office for Civil Rights Guidance, 2011).

The design of these schools would need to ensure that there are no gatekeeping exams and that each of the elements in the framework shown above are applied. Of course, this also would mean that the Legislature would need to ensure that the proposed schools, as well as all other public schools, are supported with equitable and adequate funding. This type of true public charter school would help silence the critics of certain charter schools that may be reinforcing racial and economic segregation, stripping control from local communities, “creaming” students, and inhibiting transparency of funding and accountability.

Narrow Neo-Vouchers, Such as Tax Credits, Act as Wedges for Broader Voucher Programs

The movement toward neo-vouchers – mechanisms of school privatization efforts, such as tuition tax credits and opportunity tax scholarships, that transfer public education dollars to private schools – have had mixed results, at best, and have been empirically shown to harm targeted students, at worst. By proposing to serve a targeted group of students, neo-vouchers open the door for public dollars to be transferred to private schools with no federal mandates to serve children with disabilities and no accountability for their success (Müller & Ahearn, 2007).

In Florida, for example, the tax credit program enrolled 21,493 students and awarded $118 million in total scholarships in 2007-08. Less than 10 years later, 107,095 students participated in 2017-18 with up to $698 million allocated. The tax credit cap will increase to $698,852,539 for 2017-18. (Florida Office of Program Policy Analysis & Gov’t Accountability, 2008; FLDOE, 2018)

In Indiana’s Choice Scholarship Program, 3,911 students participated in 2011-12 with $16,207,912 in total scholarships. Just four years later, 32,686 students participated in 2015-16 with $134,744,300 in total scholarships.

A multi-state legal review of neo-voucher programs targeting special education students found that states used special education neo-vouchers to drive a wedge and further a “universal choice” legislative agenda (Hensel, 2010; Falkenhagen, 2007). At least six states – Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Ohio, Oklahoma and Utah – have implemented targeted neo-voucher programs that have expanded to broader populations in the past 10 years. Twelve other states have attempted the same legislative trajectory. However, the review determined the programs to be widely ineffective, recommending, “Voucher programs should be rejected or approached with extreme caution in the future” (Hensel, 2010).

In sum, and as the remainder of the testimony demonstrates, the lack of evidence on effective outcomes stemming from neo-voucher programs, over the course of several years and across states, raises serious questions about moving forward with these policies, particularly when our most underserved students are placed on the front line of the policy.

The Research on School Privatization

Providing public school students the very best, well-rounded equitable educational opportunities is at the core of our Texas public school system. Texas must strive to meet all students’ educational, social and psychological needs. While it may be tempting to explore options other than locally-operated public schools rather than investing in them, the research strongly shows that the additional expense and cost of diverting precious resources is hardly worth it. As shown below, at best, the results are mixed, but that is in schools where there are several accountability and civil rights protections built into statute. The other privatization options, including those that are not targeted for children living in poverty and that have no accountability, operate more as private school subsidies for the very wealthy.

Research on Tax Credits, Vouchers and Other Privatization Measures

Tax credits are one of a handful of school privatization proposals shopped around in the states. The National Conference of State Legislatures reports that 17 states have adopted some form of tax credits into law as of January 2017.

Rigorous research on vouchers, tax credits and other school privatization models like charter schools shows that the effect of vouchers on student achievement and other outcomes is highly suspect at best. Below are some of the strongest studies in the field:

- A 2007 literature review of voucher and choice studies by the reputable RAND Corporation concluded that there was no definitive evidence that vouchers improved student performance (Gill, et al., 2007).

- A 2009 study by Rouse & Barrow on school vouchers and student achievement found relatively small achievement gains for students offered vouchers, most of which were not statistically different from zero. They further concluded that little evidence exists regarding the potential for public schools to respond to increased competition.

- A 2010 study by Witte, et al., of the Milwaukee voucher program found no difference in student performance (2012).

- A 2011 meta-analysis study of more than 30 studies (including the oft-cited 2011 Friedman Foundation Report) by the Center for Education Policy found that “the empirical evidence on vouchers is inconclusive and further found that any gains in student achievement are modest if they exist at all” (amicus brief, Schwartz v. López, 2016).

- A 2012 review published by the National Education Policy Center of the Friedman’s Foundation report, The Way of the Future: Education Savings Accounts for Every American Family, found that the report’s assertion that injecting competitive market pressures into public school would improve the overall system baseless (Gulosino & Leibert, 2012). Using peer-reviewed evidence, the authors invalidated the report and found that school privatization options create and exacerbate social, economic and racial inequities.

- A 2014 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research of the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program concluded that, on average, FTC students neither gained nor lost ground in achievement in math and reading compared to students nationally. Data for non-FTC Floridian students were incapable of review because those public school students were not administered the national norm-referenced test (Figlio, 2014).

- A 2014 report from the National Center for Learning Disabilities, The State of Learning Disabilities: Facts, Trends, and Emerging Issues, found that little research exists on the success outcomes of students with learning disabilities attending private schools through mechanisms of “school choice,” such as tax credits (Cortiella & Horowitz, 2014).

- A 2014 report by the National Center for Learning Disabilities cited that little is known regarding charter schools’ provision of special education services as compared to traditional public schools and questioned the effectiveness of charters’ recruitment and retention strategies for students with learning disabilities (Cortiella & Horowitz, 2014).

- A 2015 research brief by the Texas Center for Education Policy surveyed voucher studies finding that the most-disadvantaged students do not access vouchers (Jabbar, 2015).

- A 2016 study by the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans found a statistically significant negative effect on student achievement in the first two years of Louisiana’s statewide expansion of the voucher program.

- A 2016 review by Dr. Clive Belfield (Teachers College, Columbia University) of the Milwaukee voucher program by the University of Arkansas questioned the methodology of the study and concluded that there is little consideration of how voucher programs might actually influence criminality.

- A 2016 review by Lubienski & Brewer of the “Gold Standard Studies” heralded by the Friedman Foundation found that these voucher studies have mixed results that show no “discernable or consistent impact on student learning.”

- A 2017 multi-state review of voucher programs by Carnoy with the Economic Policy Institute found that students in voucher programs scored significantly lower than traditional public school students on reading and math tests and found no significant effect of vouchers leading to improved public school performance.

These analyses are consistent with studies of vouchers and tax credits showing that these programs typically do not serve the lowest poverty groups compared to other groups (Jabbar, et al., 2015). Although vouchers and tax credits can be debated on several fronts, research (in part from a 2007 study of vouchers by RAND and a 2015 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research) has suggested key design safeguards for those states still wishing to proceed with one of those privatization options:

- Target vouchers to students who are considered in at-risk circumstances.

- Maintain civil rights protections.

- Mandate an accountability system that parallels public school accountability.

- Require open admissions from participating private schools.

- Provide incentives for private schools to admit special needs students.

- Require participating private schools to set tuition at exactly the voucher value.

- Ensure all parents receive clear and timely information about voucher options.

Segregative Effect of Vouchers and Tax Credit Programs

Although school privatization advocates often allude to the expanded options available through vouchers and privatization programs, like tax credits, the research shows that these programs tend to increase racial segregation. The risk of racial segregation is especially potent where privatization laws do not have adequate protections built into the law (Mickelson & Southworth, 2008). This should be very concerning for policymakers because decreased racial segregation has been found to benefit both minority students and White students academically, socially and emotionally (Seigel-Hawley, 2012).

Studies finding segregative effects based on race and socioeconomic status include:

- A 2007 review of Florida’s voucher and tax credit programs by Harris, et al., found strong evidence of increased school racial segregation.

- A 2007 study by Huerte & d’Entremont of Minnesota’s tuition tax credit program suggests that tuition tax credits did not significantly impact school competition, as lower-income families tended not to claim the credits as frequently as already higher-income families.

- A 2009 study by Meléndez of Arizona’s Education Tax Credit program concluded that it exacerbated educational inequities since students eligible for free and reduced-price lunch were significantly less likely to benefit from ETC usage and funding.

Charter Schools

The Texas legislature created charter schools in 1995, in part, to improve student learning and to encourage different and innovative learning methods (TEC § 12.001). After 20 years of the Texas charter school “experiment,” the results show that student learning has not improved. According to the 2017 TEA accountability ratings:

- Nearly one out of every 11 charter operators (8.9 percent) received “Improvement Required” ratings compared to only one out of every 25 public school districts (3.8 percent) – and 6.1 percent of charter operators were not rated compared to only 0.2 percent of public school districts.

- More than one out of every five charter campuses (21.1 percent) failed to achieve the “met standard” or the “alternative standard,” or were “not rated” compared to fewer than one out of every 10 public school campuses (9.6 percent).

These results are relatively consistent over the last three years (Texas Education Agency, 2017). A study by IDRA in 2017 found far higher dropout rates and far lower graduation rates for students in charter schools compared to traditional public schools. (Johnson, 2017).

In spite of the dismal performance of charters, over the last 10 years, the Texas Legislature has increased its funding for charter operators from $200 million to over $2 billion. Because charter operators have no local tax bases, the state must provide 100 percent of funding for maintenance and operations (M&O). This contrasts to the state providing only between 5 percent and 62 percent of funding for Texas urban school districts located in the cities where a substantial number of charter schools exists (estimates based on TEA spreadsheet produced September 2016). The State should, instead, reinvest its resources in sustaining and improving traditional public schools as detailed further above.

| Funding for Texas Urban School Districts Where a Substantial Number of Charter Schools Exist | |||

| Name | Local M&O collections | M&O State Funding per WADA | Percent M&O State Funding |

| Austin ISD | $978,564,227 | $348 | 5% |

| Dallas ISD | $989,869,584 | $1303 | 22% |

| Fort Worth ISD | $322,331,413 | $3192 | 52% |

| Houston ISD | $1,605,682,265 | $471 | 8% |

| San Antonio ISD | $153,431,547 | $3,626 | 62% |

| Charter Schools | 0 | $5,856 | 100% |

IDRA thanks this committee for the opportunity to testify and stands ready as a resource. If you have any questions, please contact IDRA’s National Director of Policy, David Hinojosa, at david.hinojosa@idra.org or 210-444-1710, ext. 1739.

References

Ali, R., & Pérez, T.E. Guidance on the Voluntary Use of Race to Achieve Diversity and Avoid Racial Isolation in Elementary and Secondary Schools (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division and U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, December 2011). http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/guidance-ese-201111.html

Belfield, C. (April 2016). Review of the School Choice Voucher: A “Get Out of Jail” Card? (Boulder, Colo.: National Education Policy Center. http://nepc.colorado.edu/thinktank/review-school-choice

Brief for Nevada State Education Association and the National Education Association as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, Schwartz v. López, 15-OC-00207-1B (2016) (no. 69611), Doc 2016-10539.

Carnoy, M. (February 28, 2017). School Vouchers Are Not a Proven Strategy for Improving Student Achievement (Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute). http://www.epi.org/files/pdf/121635.pdf

Cortiella, C., & S.H. Horowitz. Horowitz. (2014). The State of Learning Disabilities: Facts, Trends, and Emerging Issues (New York, N.Y.: National Center for Learning Disabilities). https://www.ncld.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/2014-State-of-LD.pdf

Education Research Alliance for New Orleans. (April 20, 2016). Is There Choice in School Choice? (New Orleans, La.: Education Research Alliance for New Orleans). http://educationresearchalliancenola.org/publications/is-there-choice-in-school-choice

Figlio, D.N. (August 2014). Evaluation of the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program Participation, Compliance and Test Scores in 2012-13 (University of Florida Northwestern University and National Bureau of Economic Research). https://www.stepupforstudents.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/ftc_research_2012-13_report.pdf

Florida Department of Education (FLDOE) (Feb. 2018) Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program, Quarterly Report, Office of Independent Education and Parental Choice. http://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/7558/urlt/FTC-Feb-2018-Q-Report.pdf

Florida Office of Program Policy Analysis & Gov’t Accountability (Dec. 2008), The Corporate Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program Saves State Dollars, Report No. 08-68. http://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/5423/urlt/OPPAGA_December_2008_Report.pdf.

Gill, B., & Timpane, P.M., Ross, K.E., Brewer, D.J., Booker, K. (2007). Rhetoric Versus Reality – What We Know and What We Need to Know About Vouchers and Charter Schools (Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation). http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1118-1.html

Gulosino, C., & Liebert, J. (2012). Review of “The Way of the Future: Education Savings Accounts for Every American Family” (Boulder, Colo.: National Education Policy Center). http://nepc.colorado.edu/thinktank/review-ESA

Harris, D.N., & Herrington, C.D., Albee, A. (January 1, 2007). “The Future of Vouchers: Lessons from the Adoption, Design, and Court Challenges of Florida’s Three Voucher Programs,” Educational Policy, Vol 21, Issue 1. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0895904806297209?journalCode=epxa

Hensel, W. F. (2010). Vouchers for students with disabilities: The future of special education. JL & Educ., 39, 291.

Huerta, L. A. & d’Entremont, C. (2007). “Education Tax Credits in a Post-Zelman Era: Legal, Political and Policy Alternative to Vouchers?,” Educational Policy, January/March 21(1), 73-109.

Jabbar, H., Holme, J., Lemke, M.A., LeClair, A.V., Sanchez, J., Torres, E.M. (2015). Will School Vouchers Benefit Low-Income Families? Assessing the Evidence (Austin, Texas: Texas Center for Education Policy, University of Texas at Austin). https://www.edb.utexas.edu/tcep/resources/TCEP%20Graduate%20Seminar%20DRAFT%20Vouchers%20Memo.pdf.

Johnson, R. (2017). “Annual Dropout and Longitudinal Graduation Rates in Texas Charter Schools, 2009-2016,” Texas Public School Attrition Study, 2016-17 (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association). http://www.idra.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Annual-Dropout-and-Longitudinal-Graduation-Rates-in-Texas-Charter-Schools-2017-by-IDRA.pdf

Kahlenberg, R.D., & H. Potter. “The Original Charter School Vision,” New York Times (August 30, 2014). http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/31/opinion/sunday/albert-shanker-the-original-charter-school-visionary.html?_r=0

Lubienski, C., & Brewer. T.J. (June 29, 2016). “An Analysis of Voucher Advocacy: Taking a Closer Look at the Uses and Limitations of ‘Gold Standard’ Research,” Peabody Journal of Education, Vol. 91, Issue 4, pp 455-472. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0161956X.2016.1207438

Meléndez, P.L. (2009). “Do Education Tax Credits Improve Equity?,” dissertation (The University of Arizona). http://arizona.openrepository.com/arizona/bitstream/10150/194044/1/azu_etd_10499_sip1_m.pdf

Mickelson, R.A., & Bottia, M., Southworth, S. (2008). School Choice and Segregation by Race, Class, and Achievement (Boulder, Colo.: National Education Policy Center). http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/school-choice-and-segregation-race-class-and-achievement

Müller, E., & E. Ahearn. (April 2007). Special Education Vouchers: Four State Approaches (Alexandria, Va.: National Association of State Directors of Special Education). http://nasdse.org/DesktopModules/DNNspot-Store/ProductFiles/190_954be661-ad13-4984-86ee-27ebbae0e49b.pdf

Parents Involved in Cmty. Sch. v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, 551 U.S. 701, 789 (2007) (Kennedy, J., concurring).

Robledo Montecel, M., & Goodman, C. (2010). Courage to Connect – A Quality Schools Action Framework (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association). http://www.idra.org/change-model/courage-to-connect/

Rouse, C. E., & Barrow, L. (2009). “School Vouchers and Student Achievement: Recent Evidence, Remaining Questions,” Annual Review of Economics, 1(1), 17-42. http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.economics.050708.143354

Siegel-Hawley, G. (October 2012). How Non-Minority Students Also Benefit from Racially Diverse Schools, Research Brief (Washington, D.C.: National Coalition on School Diversity). http://www.school-diversity.org/pdf/DiversityResearchBriefNo8.pdf

Texas Education Agency. (November 14, 2017). Accountability System State Summary, District Ratings by Rating Category (Including Charter Operators) (Austin, Texas: Texas Education Agency). https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/account/2017/State_Summary_Nov_2017.html

Witte, J.F., & Wolf, P.J., Carlson, D., Dean, A. (February 2012). Milwaukee Independent Charter Schools Study: Final Report on Four-Year Achievement Gains (School Choice Demonstration Project, Department of Education Reform, University of Arkansas, 201 Graduate Education Building). Fayetteville, Ark. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED530068.pdf