House Public Education Committee Should Promote Community-Based Approaches

IDRA Testimony on Interim Charge 1B: Monitoring Implementation of HB 22 and SB 1882 (85, R)

Submitted by Dr. Chloe Latham Sikes to the House Public Education Committee

September 29, 2020

Chairman Huberty and Honorable Members of the House Public Education Committee:

IDRA (Intercultural Development Research Association) is an independent, non-partisan, education non-profit committed to achieving equal educational opportunity for every child through strong public schools that prepare all students to access and succeed in college. Thank you for considering our testimony.*

In this testimony, we review the implications of HB 22 and SB 1882, including data showing the harms of the bills and how ineffective accountability systems can lead to misidentified campus needs and to poor outcomes for students and school communities.

House Bill 22 (85th Texas Legislature, Regular Session)

Public school accountability systems must function as a tool for the local community to hold their schools accountable and must not harm the very students that schools serve. HB 22 launched the A-F accountability system for Texas public schools based on three domains of student and school performance. The bill successfully reduced the performance domains from five to three yet maintains an overreliance on the STAAR test as a performance indicator across domains. This both heavily weights a single measure of student performance, which is not a holistic form of assessment, and exacerbates inequities in assessing student learning and ability across racial/ethnic groups, socioeconomic status, and designations as English learners or in special education.

Research shows that standardized tests, such as STAAR, perpetuate racial biases in their design and implementation that privilege white, middle-class students and disenfranchise students of color and those from lower-income households (McNeil, Coppola, Radigan, & Heilig, 2008; Valenzuela, 2005). For example, the methods for determining “passing” score levels for standardized tests rely on historical assumptions about the lower performance of students of color and from lower-incomes (Knoester & Au, 2017). Students who attend “low-scoring” schools often receive narrowed, test-centered curriculum that further stunts expansive critical inquiry and exploratory learning opportunities (Valenzuela, 2005), which perpetuates racial inequities in education (Pearman, 2020).

In addition, research shows that assigning overly simplistic A-F letter grades to school campuses and districts obscures any real assessment of actual student performance and campus improvement (Tanner, 2016). The letter grading accountability system relies heavily on standardized test score performance as a narrow measure of campus and district performance rather than holistic metrics that account for school climates, learning progress, student and family engagement, and social-emotional learning.

Assigning letter grades can lead to overreaching accountability consequences that punish schools that serve large proportions of students of color. In fact, the A-F rating system has been leveraged against school districts that serve large populations of students of color and from low-income households in order to institute state sanctions. For instance, Houston ISD received a B rating as a district, but received notice of state sanctions due to a single campus receiving an F rating (the district has more than 280 schools). In response to the campus’ low rating, the TEA Commissioner lowered the accreditation status of the entire district, which the state alleges provided the grounds for takeover actions. This sparked massive community outcry, controversy, and litigation at state expense (See Wilson & Sikes, 2020).

Senate Bill 1882 (85th Texas Legislature, Regular Session)

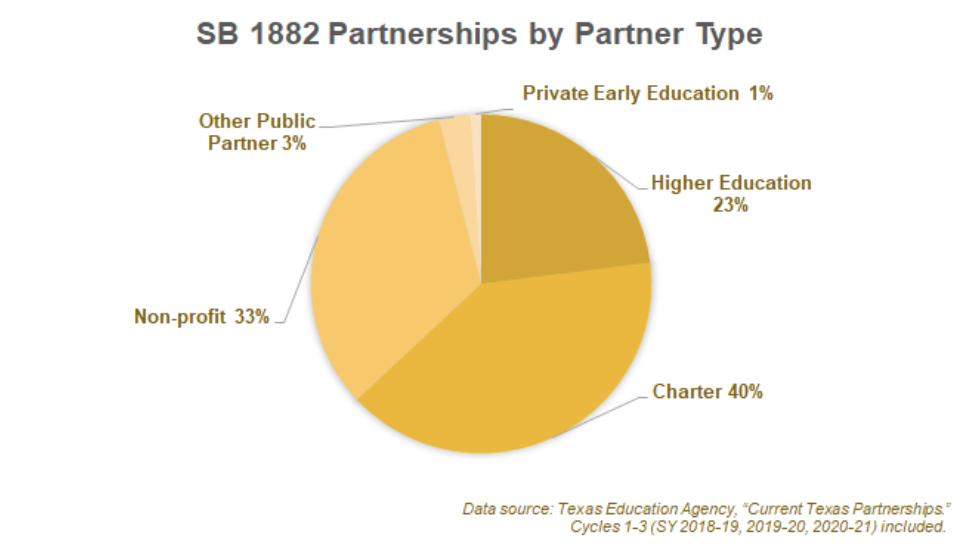

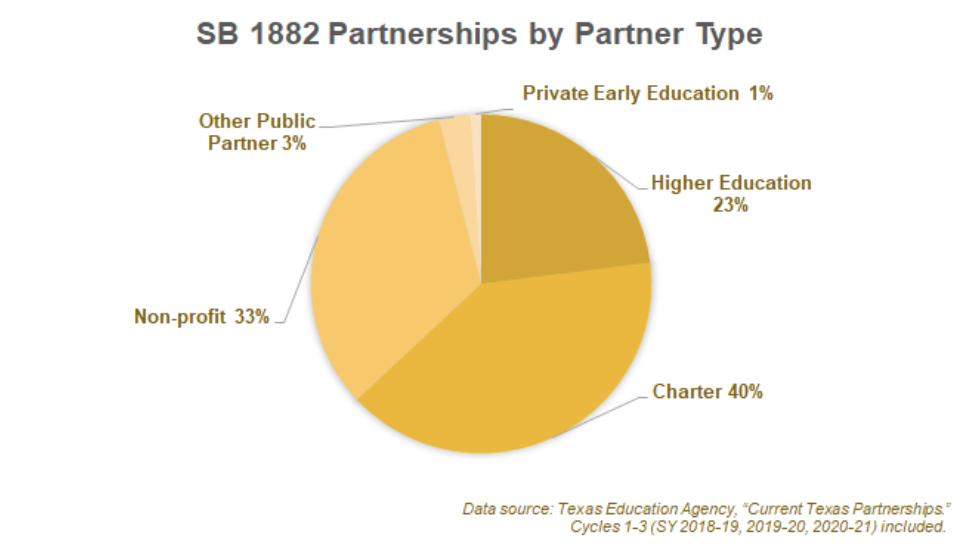

SB 1882 was designed to allow school districts to create partnerships between campuses and non-profit organizations, charter networks or institutions of higher education in order to facilitate school turnaround plans for schools rated in need of improvement in the state accountability system. These partnerships were fraught from the start because of the potential for privately-managed organizations, such as private charter management organizations, to assume authority of a campus’s operations and governance without substantial community input through the partnerships.

As school districts across the state have entered into 1882 partnerships, we are seeing the creation of a patchwork of private-public partnerships in districts with schools under different contracts with different operating partners. Research demonstrates that the success of private-public partnerships in schools depends on the nature of their agreements, the ensured level of public accountability (Horsford, Scott, & Anderson, 2019), and family engagement (NEA, 2011; Preston, Goldring, Berends, & Cannata 2012). But the law does not require 1882 partnerships to ensure the recommended levels of accountability and family engagement. This can result in an 1882 partner altering the academic focus of a public school campus without two-way family engagement. This narrow intervention can fail to identify and exacerbate existing issues in a district, including lack of financial and material resources, management issues that could be resolved locally, or the need for enhanced community supports in health, employment, transportation and food security.

New rules from the Texas Education Agency published in March 2020 expanded the Commissioner of Education’s authority in 1882 partner application decisions and changed the application rules to grant even further control to the operating partners over public school campuses. The original law and new rules have several implications:

- More charter organizations and private educational management organizations could enter into various 1882 partnerships control public school funds. New rules require that partners have independent governing boards from the school district and maintain full control of the school campus budgets.

- Challenges to transparency and public oversight will grow because of the patchwork of partnerships and varying contract arrangements over the operations, campus governance and funding of 1882-contracted campuses.

- Funding inequities within districts will rise between charter-managed and district-managed schools because 1882-contracted campuses receive the greater of charter or district-level funds. Charter schools on average receive more funds based on a flat statewide rate instead of specific district rates.

- School districts could enter into more multi-year district contracts with private partners without supporting evidence of academic improvements.

While the state is only in Cycle 3 of the SB 1882 partnerships, it is clear that the bill has opened the door for private management of public schools.

Recommendations

IDRA recommends that several local and systemic changes be made for public school accountability and improvement:

- Districts should adopt community-based approaches that evidence shows support school improvements, such as community schools.

- The broad discretion of the Commissioner in Texas Education Code, Chapter 39, to enact state sanctions, such as the appointment of a conservator or board of managers of a public district should be reduced. Instead, TEA should be instructed to promulgate rules and provide resources that promote school supports and community-based approaches that support responsible local school board governance and teaching and learning best practices.

- The legislature should replace the A-F accountability system in favor of opportunity-to-learn metrics that identify specific areas for support – such as in-district resource allocation, college preparedness, and teacher quality – instead of relying on overly-punitive and ineffective responses to school district needs. Removing the stick of state sanctions can encourage districts to engage in the longer-term, sustainable community partnerships and authentic family engagement that has been shown to improve outcomes for students, rather than enter consequential contracts with outside organizations.

IDRA is available for any questions or further resources that we can provide. Thank you for your consideration. For more information, please contact Chloe Latham Sikes, Ph.D., IDRA Deputy Director of Policy, at chloe.sikes@idra.org.

*Portions of the SB 1882 testimony appear in the May 2020 IDRA Newsletter article, “Implications of SB 1882 Patchwork of Partnerships.” A full reference list on that topic can be found via the link.

Additional Resources

Knoester, M., & Au, W. (2017). Standardized testing and school segregation: like tinder for fire?, Race Ethnicity and Education, 20(1), 1-14. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288684876_Standardized_testing_and_school_segregation_like_tinder_for_fire

Latham Sikes, C. (May 2020). Implications of Texas SB 1882 Patchwork of Partnerships, IDRA Newsletter. https://www.idra.org/resource-center/implications-of-texas-sb-1882-patchwork-of-partnerships/

McNeil, L.M., Coppola, E., Radigan, J., & Heilig, J.V. (2008). Avoidable losses: High-stakes accountability and the dropout crisis. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 16(3), 1-48. https://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/view/28

Pearman, F. (2020). Collective Racial Bias and the Black-White Test Score Gap, Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis working paper. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED605972.

Tanner, J. (November 2016). The A-F Accountability Mistake. The Texas Accountability Series. Austin, Texas: The Texas Association of School Administrators. http://www.futurereadytx.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/A-F-mistake.pdf

Texas Education Agency. (2020). Current Texas Partnerships. Austin, Texas: Texas Education Agency. https://txpartnerships.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Current-Texas-Partnerships-2020-2021.pdf

Valenzuela, A. (Ed.). (2005). Leaving Children Behind: How” Texas-Style” Accountability Fails Latino Youth. Albany, N.Y.: Suny Press.

Wilson, T., & Latham Sikes, C. (2020). Another Zero-Tolerance Failure – State Takeovers of School Districts Don’t Work. San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association. https://www.idra.org/resource-center/another-zero-tolerance-failure-state-takeovers-of-school-districts-dont-work-issue-brief/

The Intercultural Development Research Association is an independent, non-profit organization led by Celina Moreno, J.D. Our mission is to achieve equal educational opportunity for every child through strong public schools that prepare all students to access and succeed in college. IDRA strengthens and transforms public education by providing dynamic training; useful research, evaluation, and frameworks for action; timely policy analyses; and innovative materials and programs.