• by Albert Cortez, Ph.D. • IDRA Newsletter • February 2009

In July of 2007, Judge William Wayne Justice heard a complaint from plaintiffs who questioned the adequacy of the Texas’s compliance monitoring of state-mandated bilingual education and English as a second language (ESL) programs at the secondary school level. Judge Justice is the district federal judge who retained oversight of the court case that addressed the vestiges of past discrimination against Mexican Americans in Texas. In the case, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) and Multicultural Education and Training Advocates (META) asserted that the new Texas Performance Based Monitoring Assessment System (PBMAS) fails to adequately monitor districts’ compliance with state bilingual and ESL program requirements. More specifically the plaintiffs charged that the PBMAS fails to incorporate mechanisms to ensure that school districts are not under-identifying students as limited-English-proficient and that it aggregates LEP student data across three to 11 grade levels in a manner that masks LEP student under-performance at the secondary level.

Judge Justice ruled in July of 2007 that the existing state compliance monitoring system does comply with state and federal requirements. However, a year later on July 24, 2008, he issued a revised court order granting the plaintiff’s motion to require the Texas Education Agency (TEA) to “monitor, enforce and supervise programs for limited-English-proficient students in Texas so as to ensure that those students receive appropriate educational programs and equal educational opportunities.”

In this ruling, the district federal court found that the state of Texas failed to establish a monitoring system that addressed the needs of students of limited English proficiency by: (1) failing to establish oversight procedures that would help identify districts who may have been substantially under-reporting numbers of LEP student enrolled; (2) aggregating student achievement data in a way that masked secondary level schools’ under-performance; and (3) was operating a program that ‘failed’ secondary level LEP students in Texas and was ineffective in closing the gap in achievement between LEP and non-LEP students.

This is the latest in a series of rulings issued by Judge Justice in U.S vs. Texas and is specifically related to the 1981 ruling in which the court held that the state had “violated the equal protection clause and Section 1703(f) of the Equal Educational Opportunities Act by failing to take appropriate action to address the language barriers of LEP students and by failing to remove the disabling vestiges of past de jure discrimination against Mexican American students” (Texas [LULAC], 506 F. Supp. At 428-34).

Later in 1981, the state of Texas adopted and implemented Senate Bill 477, which required school systems to establish bilingual or ESL programs for students identified as LEP. This included on-site monitoring requirements and the implementation of bilingual programs at the elementary level and ESL programs at the secondary level.

In 2003, the Texas legislature modified its procedures for monitoring school district compliance with state mandates, opting to transition into an electronic-based, data-driven monitoring system that abandoned on-site monitoring in favor of “performance based oversight procedures” that relied almost exclusively on the state comprehensive district and school level databases. As part of that effort, the state adopted the PBMAS to monitor the performance of districts’ special population programs. Three major data-related flaws identified by the Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) in the new PBMAS included:

-

lack of a review process of districts where identification of LEP students tended to fall well below the levels of districts with similar numbers of language-minority students;

-

lack of procedures for reviewing cases where parent requests that students be exempted from bilingual or ESL participation notably exceeded statewide averages; and

-

aggregating elementary- and secondary-level ELL performance data in a way that masked under-achievement of LEP students in middle and high school.

Data Aggregation Hides Under-Performing Secondary Schools

In this third area, IDRA analyses revealed major flaws in the PBMAS procedures used to trigger corrective action in programs serving LEP populations. This monitoring process involved “averaging” LEP student performance in individual subject areas (reading, math, etc.) across all grades tested in that subject.

This meant that LEP student scores in reading/language arts and math (which are assessed in grades 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11) are all added together, from which the percent of all LEP students who meet state passing standards is then computed.

An obvious problem with the process is that programs for LEP students differ radically at the elementary and secondary levels in Texas. And the cross-level averaging process tends to co-mingle that data. More importantly, as plaintiffs argued, the PBMAS’s cross-grade level calculations tend to mask secondary level LEP under-achievement by lumping together the lower performing secondary level ESL performance data with the higher elementary level bilingual education performance measures.

To demonstrate this masking effect, IDRA disaggregated the elementary and secondary level data and uncovered a total of 250 underachieving secondary-level schools that were imbedded in school districts found to be performing at acceptable levels when rated under the aggregated PBMAS approach. Judge Justice agreed that the state’s cross-school level aggregation of LEP data resulted in masking secondary level program under-performance.

Procedures Overlook Under-Identification and High Rates of Parent Denials

The court also ruled that existing TEA oversight procedures overlooked LEP under-identification. Since the PBMAS relies primarily on Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills results and dropout data, the absence of students who were unidentified due to flaws in school district identification procedures would be overlooked in such a system. Likewise, the numbers of parent denials were not included in the data considered in PBMAS, making cases where school district denial levels notably exceeded state trends invisible to that system.

Program’s Inability to Close the Achievement Gap

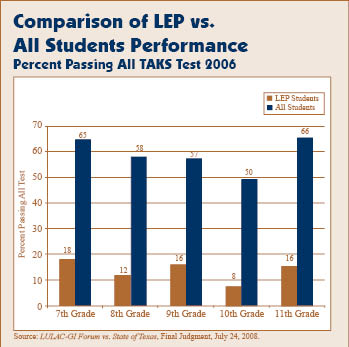

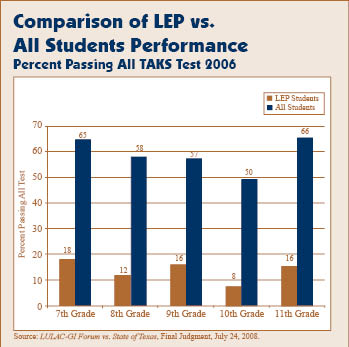

In addition to his rulings related to monitoring and oversight, another facet of the judge’s major findings focused on the state ESL program’s inability to close the achievement gap among LEP and non-LEP students. Using the state’s own TAKS data, the judge noted that large, persistent and significant gaps in achievement between LEP and non-LEP students proved that the PBMAS was flawed and “not equality based.”

In presenting that finding, the court clarified that LEP program performance expectations should be designed to reduce the gap in achievement between LEP and non-LEP students and not merely on whether LEP students had performed at some arbitrarily-decided level designated in the PBMAS. The court then went on to cite the LEP and non-LEP performance levels by grade level and subject area, noting the extent of gap in each. Of particular concern to the court were the large achievement gaps between LEP and non-LEP students who were enrolled in grades seven through 12. The court concluded: “Secondary LEP students in bilingual education fail terribly under every metric. [They] drop out at a rate at least twice that of the all-students category… are retained at rates consistently double that of their peers… [and] perform worse then their peers by a margin of 40 percent or more on the TAKS all-tests category.”

The judge concluded that the “totality of the data establishes causation,” noting: “The court holds that sufficient evidence of student failure can establish that educational agencies have not met their obligation to overcome language barriers. The failure of secondary LEP students under every metric clearly and convincingly demonstrates student failure, and accordingly, the failure of the ESL program in Texas.”

Responding to state arguments that other mechanisms compensated for gaps in the PBMAS, the judge concluded that other monitoring mechanisms, including the No Child Left Behind Act and the Texas school accountability system, do not sufficiently compensate for the flaws of the PBMAS as it relates to LEP students.

In his concluding points, the judge stated: “Defendants must soon rectify the monitoring failures and begin implementing a new language program for secondary students.” Reflecting intent to be non-prescriptive, however, the court noted that “as a non-binding option, the secondary program could consist of a variation of the current ESL program with substantially enhanced remediation.”

Based on his review of all relevant evidence, the court required the state of Texas to modify its monitoring system to:

-

assess possible under-identification in specific school districts;

-

ensure that monitoring teams overseeing local district operations, include personnel who are certified in bilingual or ESL programs; and

-

disaggregate elementary and secondary LEP data for PBMAS purposes.

Additionally the court ordered the state to revise the existing secondary LEP program to reduce the achievement gap differential between LEP and non-LEP pupils. To expedite compliance, the court ordered that the state develop a plan to address the issues raised no later than January 31, 2009.

The Texas Response

Rather than acknowledging the documented shortcomings of its monitoring and secondary program operations, the state of Texas, through the Attorney General’s Office, chose to challenge the court’s findings and signaled its intent to appeal the ruling in August of 2008. The state subsequently filed a request to the court asking it to reconsider its latest ruling and to stay its order that the agency develop a plan for addressing the court decision by January 31. In its brief, the state argued that complying with the requirements would require legislative action and appropriation of additional revenue – both actions not under the purview of the state education agency.

Plaintiff attorneys submitted briefs opposing the request for a modified order and the related staying of the standing court order. The federal district court reviewed the briefs and rejected the state of Texas’ request, finding that the agency and the commissioner did in fact have authority to implement at least some of the changes required. The court also proposed that if implementation of the plan that is developed by the state requires additional resources or legislative authority, those issues can be dealt with at that time.

As of this writing, the state of Texas has submitted its appeal to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals for the Western District. It is unknown at this time how long the court may take to respond to a request for a stay of Judge Justice’s order and a review of his judgment in the case.

In the interim, state legislators have indicated that an examination and possible reform of existing policies might be considered in the upcoming session, with two senate leaders currently involved in drafting language that addresses the court’s concerns related to program monitoring and secondary-level LEP program quality. Whether the state of Texas initiates some reforms or is forced to take more decisive action will be more evident in the next few months as the Texas legislature reconvenes and the court of appeals issues its own ruling on the case.

Albert Cortez, is director of IDRA Policy. Comments and questions may be directed to him via e-mail at feedback@idra.org.

[©2009, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the February 2009 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]