• By María “Cuca” Robledo Montecel, Ph.D. • IDRA Newsletter • September 2009

If the past decade is prologue to the next, it is difficult to know if we will have both the clarity and urgency that is needed to do the hard work of sustainable change. On the one hand, the last decade has seen a shift toward an expectation that schools “bring all students to high standards of academic proficiency” (Mosher and Smith, 2009). Also, more Americans now believe that education beyond high school is a necessity, with a large shift toward that belief occurring since the year 2000 (Lumina, 2009).

On the other hand, there is much evidence that the last decade has seen a widening of the economic and education gaps and that the “pressure for reform has increased but is not yet the reality” (Fullan, 2007).

Today and over the next several years, the grip of the economic crisis and the din of competing priorities may put education in a holding pattern that is interrupted only to wish for a return to the good ole days that in reality weren’t so good for much of the population; to bemoan the next school, district, state or national report card; or to pine for the next magic silver bullet.

Thankfully, there is another option. We can pursue shared prosperity by keeping our eyes on the goal of quality education for every child in every school understanding that education matters, community voices matter in education, and much is known about what to do.

Education Matters to Shared Prosperity

Robust research evidence indicates that the quality of education affects economic opportunity for individuals and outcomes for society across generations. Data from the Economic Mobility Project (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2009) underscore the connection between education and economic opportunity and the key role that educational opportunity plays in getting a fair chance at the American Dream.

There is also strong evidence that education matters to individuals and to society in other critical areas, including health, longevity and the vitality of civic life. Goals for the Common Good: Exploring the Impact of Education identifies critical areas linked to educational attainment, synthesizes research findings, and provides links to an online Common Good Forecaster (American Human Development Project, 2009).

However, disparities and gaps in educational opportunity and outcomes continue to divide Americans based on class and color. The average low-income high school senior has the same reading level as the average middle-class eighth grader, and the percentage of high-poverty schools that are high-performing is 1.1 percent compared to 24.2 percent of low-poverty schools that are high-performing (Kahlenberg, 2008). If you are Black or Latino, you are more likely to attend a high-poverty, segregated, under-funded school that is unable to graduate students and is unable to prepare students for college or today’s competitive job market (Alliance for Excellent Education, 2009; Alliance for Excellent Education and the College Board, 2009).

Community Voices Matter in Education

Education matters to the individual and to society. But the quality of education provided in a local school system affects the local community in important ways. To examine the impact of educational quality on the local community, RAND researchers focused on a substantial body of literature and found strong evidence of: (1) effects on housing values in the school attendance area with an increase of 1 percent in reading or math scores associated with a 0.5 percent to 1 percent increase in property values; (2) effects on crime rates with a one-year higher educational level in a community associated with a 13 percent to 27 percent lower incidence of murders, assaults, car thefts and arson; and (3) effects on tax revenues with increased earnings and sales, and higher property tax revenues from residences and businesses. There also was evidence that educational quality in the community is associated with greater civic participation in that community, including more voter participation, more tolerance and acceptance of free speech, more involvement in community arts and culture, and higher newspaper readership (Carroll and Scherer, 2008).

Maintaining urgency and clarity in sustainable educational reform depends in large measure on community will and informed engagement at the local community level. Schools, after all, belong to the community, and change is too important to be left to schools alone. Community engagement that is based on active participation by both the school and the community produces results for students (Petrovich, 2008; Mediratta, et al., 2008; Levin, 2008). IDRA work in building and informing school-community teams demonstrates success in these partnerships and coalitions (Rodríguez and Scott, 2007; Montemayor, 2008; IDRA, 2008).

The Harlem Children’s Zone has established a cluster of community programs to serve neighborhood families and their children from birth to college graduation (Shulman, 2009). This “unique, holistic approach to rebuilding a community” is generating dramatically improved student achievement and parent engagement as well as positive financial impact to the neighborhood (HCZ web site).

Community buy-in and oversight stemming from shared understandings and data about the why, the how, and the results of school change is a critical but largely untapped change strategy in school reform efforts. For example, community teams can use data about their local dropout and graduation rates, disaggregated by subgroups, and data on the related school factors of parent involvement, student engagement, curriculum access and teaching quality in order to develop comprehensive plans of action to graduate all students (Robledo Montecel, 2007).

Much Is Known About What to Do

There is a growing sense around the country that real, long-lasting change is urgent, indispensable and possible. The U.S. Department of Education is working with others to frame and fund an agenda that includes setting benchmarked standards, developing data systems to track growth and tailor instruction, boosting the quality of teachers and principals, and turning around the lowest-performing schools. Forty-six states have signed on to create benchmarked K-12 standards that prepare students for the 21st Century global knowledge-based economy.

Foundations also are focusing their strategies and leveraging their investments on education reform by setting goals and funding the detailed work that will achieve those goals. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation will invest $500 million over the next five years in learning how to improve and measure teacher quality. The Lumina Foundation is focused on assuring that, by 2025, the proportion of Americans with higher education credentials increases to 60 percent from the current 39 percent.

Unprecedented successes in unexpected places are defying the perception that achievement gaps are inevitable (Chenoweth, 2007). For example, IDRA led a group of middle school teachers, a principal, counselor and social worker to create a small professional learning community, in conjunction with IDRA’s Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program, focused on the academic success of students who were considered at risk of dropping out of school. Both teaching quality and student engagement improved, transforming student results (Montemayor and Cortez, 2007).

High-poverty urban schools are improving demonstrably by using additional monies coming to them by court order to good effect. In

New Jersey

, poor schools that received an infusion of funds as a result of the Abbott vs. Burke case are demonstrating improved student achievement (Anrig, 2009). In

Texas

, student achievement on national tests improved in 2008 due in part to a decade of improved and equitable funding that had been provided to

Texas

schools (Cortez, 2009).

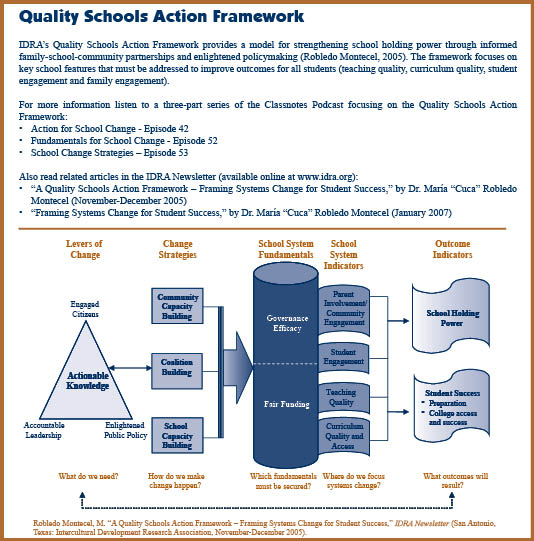

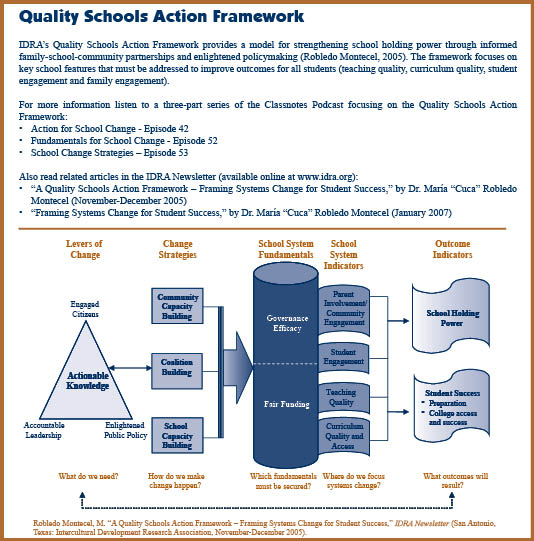

For the last four years, IDRA has utilized the Quality Schools Action Framework (Robledo Montecel, 2005) as a frame for our work in educational reform (see box below). The Quality Schools Action Framework brings together what we know about educational change efforts. The framework:

- is empirical, experiential and practical.

- is results oriented and tracks expected outcomes both on (a) student metrics of success at many levels including college, and (b) school metrics of success focused on the school’s ability to keep students in school and learning through to graduation.

- focuses attention and action, singularly and in tandem, on the four system indicators that are key to success: parent and community engagement, student engagement, quality teaching, and curriculum quality and access.

- points to governance efficacy and fair funding as crucial fundamentals that interact with indicators and outcomes.

- highlights change strategies that build individual and collective capacity within and across school and community.

- couples capacity-building with active coalitions that have an urgent agenda to produce results for students.

- positions knowledge-building and utilization as a core feature of accountable leadership, enlightened policy, and engaged citizens.

- uses knowledge, information, evidence and outcome data not only as “rear mirror” assessments but also as integral to informing present and future strategy.

A number of our partner schools and coalition organizations have used the framework and the companion online portal to assess baselines, plan and implement strategy, and monitor progress in educating all students to high quality (Posner, 2009).

Our experience with the framework so far is that it is a useful tool in many ways: to conceive, design and manage change at the school or district level; to encourage thoughtful and coherent selection of best practices that are grounded in the reality of the schools and their communities; to focus on particular strategies and/or instructional approaches (e.g., bilingual education) without losing track of the contexts that matter (e.g., teaching quality, school/district leadership, funding); to inform evidence-based community collaboration and oversight in productive ways; and to inform meaningful comparisons across campuses and districts.

As a “change model,” the Quality Schools Action Framework also may prove useful in making the link between benchmarked standards and sustainable school reform that ties desired outcomes to indicators of quality at the local level.

Lisbeth Schorr (2009) has eloquently stated that the “search for silver bullets is giving way to an understanding that, to make inroads on big social problems, reformers must mobilize multiple, interacting strategies that take account not only individual needs but also the power of context.” It is at the local level, with schools and communities working together, that the power of context can be a source of genuine and long-lasting change that benefits every student in every school with a quality education.

Resources

Alliance for Excellent Education and College Board. Facts for Education Advocates: Demographics and the Racial Divide (Washington, D.C.: Alliance for Excellent Education, copublished with College Board, 2009). https://34.231.97.227/wp-content/uploads/Facts_For_Education_Adv_Oct2008.pdf, https://all4ed.org/reports-factsheets/facts-for-education-advocates-an-overview-copublished-with-the-college-board/

Alliance for Excellent Education.Students of Color and the Achievement Gap (Washington, D.C.: Alliance for Excellent Education and College Board, 2009).

American Human Development Project. Goals for the Common Good: Exploring the Impact of Education (American Human Development Project and United Way, 2009).

http://measureofamerica.org/file/common_good_forecaster_full_report.pdf http://www.measureofamerica.org/forecaster/

Anrig, G. Educational Strategies That Work (New York, N.Y.: The Century Foundation, March 2009).

Carroll, S.J., and E. Scherer. The Impact of Educational Quality on the Community: A Literature Review (Santa Monica, Calif: The RAND Corporation, 2008).

Chenoweth, K. It’s Being Done: Academic Success in Unexpected Schools (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Education Press, 2007).

Cortez, A. The Status of School Finance Equity in Texas– A 2009 Update (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, 2009).

Duncan, A. “Partners in Reform,” remarks before the National Education Association recognizing the 45th anniversary of the enactment of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination in public schools (Washington, D.C.: U.S.Department of Education, July 2, 2009). http://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/2009/07/07022009.html http://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/2009/07/07022009.pdf

Fullan, M. The New Meaning of Educational Change, fourth edition (New York, N.Y.: Teachers College Press, Columbia University, 2007) pg. 6.

Intercultural Development Research Association. Capacity Building Evaluation for the Rio Grande Valley Grantees, unpublished report memorandum to The Marguerite Casey Foundation (January 15, 2008).

Kahlenberg, R.D. Can Separate Be Equal? The Overlooked Flaw at the Center of No Child Left Behind (New York, N.Y.: The Century Foundation, 2008).

Levin, B. How to Change 5000 Schools. A Practical and Positive Approach for Leading Change at Every Level (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Education Press, 2008).

Lumina Foundation for Education. Lumina Foundation’s Strategic Plan: Goal 2025 (Indianapolis, Ind.: 2009).

Mediratta, K., and S. Shah, S. McAlister, D. Lockwood, C. Mokhtar, N. Fruchter. Organized Communities, Stronger Schools: A Preview of Research Findings (Providence,

R.I.: Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University, 2008).

Montemayor, A.M. “Authentic Consultation – NCLB Outreach Leadership and Dialogues for Parents, Students and Teachers,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, June-July 2008).

Montemayor, A.M., and J.D. Cortez. “Valuing Youth – Reflections from a Professional Learning Community,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio,Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, March 2007).

Mosher, F.A., and M.S. Smith. “The Role of Research in Education Reform from the Perspective of Federal Policymakers and Foundation Grantmakers,” in The Role of Research in Educational Improvement (John D. Bransfor, Deborah J. Stipek, Nancy J. Vyie, Louis M. Gomez, and Diana Lam, eds.) (Cambridge,Mass.: Harvard Education Press, 2009) pg. 19.

Petrovich, J. A Foundation Returns to School: Strategies for Improving Public Education (New York: Ford Foundation, 2008).

The Pew Charitable Trusts. The Economic Mobility Project (Philadelphia, Pa.: The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2009).

Posner, L. “Actionable Knowledge: Putting Research to Work for School Community Action,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio,Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, August 2009).

Posner, L., and H. Bojorquez. “Knowledge for Action – Organizing School-Community Partnerships Around Quality Data,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, January 2008).

Robledo Montecel, M. “Graduation for All Students – Dropout Prevention and Student Engagement Strategies and the Reauthorization of the No Child Left Behind Act,” testimony before the Committee on Education and Labor, U.S. House of Representatives, in a hearing on “NCLB: Preventing Dropouts and Enhancing School Safety” (April 23, 2007).

Robledo Montecel, M. “A Quality Schools Action Framework,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, November-December 2005).

Rodríguez, R.G., and B. Scott. “Expanding Blueprints for Action – Children’s Outcomes, Access, Treatment, Learning, Resources, Accountability,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, May 2007).

Schorr, L. “Innovative Reforms Require Innovative Scorekeeping,” Education Week (August 26, 2009).

Shulman, R. “Harlem Program Singled Out as Model: Obama Administration to Replicate Plan in Other Cities to Boost Poor Children,” Washington Post (August 2, 2009).

María “Cuca” Robledo Montecel, Ph.D., is the president and CEO of IDRA. Comments and questions may be directed to her via e-mail at feedback@idra.org.

[©2009, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the September 2009 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]