Testimony of IDRA presented for the Senate Education Committee, July 21, 2017

Thank you for allowing the Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) the opportunity to provide written testimony of its research and analysis on school privatization, tax credit programs, and other “neo-vouchers.” In addition, IDRA addresses the other issues raised in SB 2 further below.

Founded in 1973, IDRA is an independent, non-profit organization that is dedicated to assuring equal educational opportunity for every child through strong public schools that prepare all students to access and succeed in college. Throughout its history, IDRA has conducted extensive research and analysis on a range of Texas and national educational issues impacting public school children, including school finance and school privatization options. For those reasons, we are testifying on SB 2.

Based on its review of the research, IDRA recommends that the Texas Legislature:

1. Improve its support for building strong public schools by providing greater equitable educational opportunities for all students across the state, including limiting facilities funding to traditional public schools and eliminating or modifying the hardship exemption;

2. Seriously reconsider avoiding school privatization options, such as vouchers and neo-vouchers, such as tax credits, which research shows: (1) fail to deliver on the promise of better learning opportunities and student performance; (2) siphon limited resources from local community schools; (3) open up the potential for violating students’ civil rights; (4) hinder transparency and accountability; and (5) tend to lead to more schools being racially segregated.

Narrow Neo-Vouchers, Such as Tax Credits, Act as Gateways for Broader Voucher Programs

The movement toward neo-vouchers – mechanisms of school privatization efforts, such as tuition tax credits, that transfer public education dollars to private schools – have had mixed results, at best, and have been empirically shown to harm targeted students, at worst. By proposing to serve a targeted group of students, neo-vouchers open the door for public dollars to be transferred to private schools with no federal mandates to serve children with disabilities and no accountability for their success (Müller & Ahearn, 2007).

In Florida, for example, the tax credit program started with 21,493 students and $118,100,000 in total scholarships in 2007-08. Less than 10 years later, 78,664 students participated in 2015-16 with $418,493,458 allocated. The tax credit cap will increase to $698,852,539 for 2017-18. (Fla. DOE, 2008; 2016).

In Indiana’s Choice Scholarship Program, 3,911 students participated in 2011-12 with $16,207,912 in total scholarships. Just four years later, 32,686 students participated in 2015-16 with $134,744,300 in total scholarships.

A multi-state legal review of neo-voucher programs targeting special education students found that states used special education neo-vouchers as a gateway to further a “universal choice” legislative agenda (Hensel, 2010; Falkenhagen, 2007). At least six states – Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Ohio, Oklahoma and Utah – have implemented targeted neo-voucher programs that have expanded to broader populations in the past 10 years. Twelve other states have attempted the same legislative trajectory. However, the review determined the programs to be widely ineffective, recommending, “Voucher programs should be rejected or approached with extreme caution in the future” (Hensel, 2010).

In sum, and as the remainder of the brief demonstrates, the lack of evidence on effective outcomes stemming from neo-voucher programs, over the course of several years and across states, raises serious questions about moving forward with these policies, particularly when our most underserved students are placed on the front line of the policy.

The Research on School Privatization

Providing public school students the very best, well-rounded equitable educational opportunities is at the core of our Texas public school system. Texas must strive to meet all students’ educational, social and psychological needs. While it may be tempting to explore options other than locally-controlled public schools rather than investing in them, the research strongly shows that the additional expense and cost of diverting precious resources is hardly worth it. As shown below, at best, the results are mixed, but that is in schools where there are several accountability and civil rights protections built into statute. The other privatization options, including those that are not targeted for children living in poverty and that have no accountability, operate more as private school subsidies for the very wealthy.

Research on Tax Credits, Vouchers and Other Privatization Measures

Tax credits are one of a handful of school privatization proposals shopped around in the states. The National Conference of State Legislatures reports that 17 states have adopted some form of tax credits into law as of January 2017.

Rigorous research on vouchers, tax credits and other school privatization models like charter schools shows that the effect of vouchers on student achievement and other outcomes is highly suspect at best. Below are some of the strongest studies in the field:

- A 2007 literature review of voucher and choice studies by the reputable RAND Corporation concluded that there was no definitive evidence that vouchers improved student performance (Gill, et al., 2007).

- A 2009 study by Rouse & Barrow on school vouchers and student achievement found relatively small achievement gains for students offered vouchers, most of which were not statistically different from zero. They further concluded that little evidence exists regarding the potential for public schools to respond to increased competition.

- A 2010 study by Witte, et al., of the Milwaukee voucher program found no difference in student performance (Witte, et al., 2012).

- A 2011 meta-analysis study of more than 30 studies (including the oft-cited 2011 Friedman Foundation Report) by the Center for Education Policy found that “the empirical evidence on vouchers is inconclusive and further found that any gains in student achievement are modest if they exist at all” (amicus brief, Schwartz v. Lopez, 2016).

- A 2012 review published by the National Education Policy Center of the Friedman’s Foundation report, The Way of the Future: Education Savings Accounts for Every American Family, found that the report’s assertion that injecting competitive market pressures into public school would improve the overall system baseless (Gulosino & Leibert, 2012). Using peer-reviewed evidence, the authors invalidated the report and found that school privatization options create and exacerbate social, economic and racial inequities.

- A 2014 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research of the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program concluded that, on average, FTC students neither gained nor lost ground in achievement in math and reading compared to students nationally. Data for non-FTC Floridian students were incapable of review because those public school students were not administered the national norm-referenced test (Figlio, 2014).

- A 2014 report from the National Center for Learning Disabilities, The State of Learning Disabilities: Facts, Trends, and Emerging Issues, found that little research exists on the success outcomes of students with learning disabilities attending private schools through mechanisms of “school choice,” such as tax credits (Cortiella & Horowitz, 2014).

- A 2014 report by the National Center for Learning Disabilities cited that little is known regarding charter schools’ provision of special education services as compared to traditional public schools and questioned the effectiveness of charters’ recruitment and retention strategies for students with learning disabilities (Cortiella & Horowitz, 2014).

- A 2015 research brief by the Texas Center for Education Policy surveyed voucher studies finding that the most-disadvantaged students do not access vouchers (Jabbar, 2015).

- A 2016 study by the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans found a statistically significant negative effect on student achievement in the first two years of Louisiana’s statewide expansion of the voucher program.

- A 2016 review by Dr. Clive Belfield (Teachers College, Columbia University) of the Milwaukee voucher program by the University of Arkansas questioned the methodology of the study and concluded that there is little consideration of how voucher programs might actually influence criminality.

- A 2016 review by Lubienski & Brewer of the “Gold Standard Studies” heralded by the Friedman Foundation found that these voucher studies have mixed results that show no “discernable or consistent impact on student learning.”

- A 2017 multi-state review of voucher programs by Carnoy with the Economic Policy Institute found that students in voucher programs scored significantly lower than traditional public school students on reading and math tests and found no significant effect of vouchers leading to improved public school performance.

These analyses are consistent with studies of vouchers and tax credits showing that these programs typically do not serve the lowest poverty groups compared to other groups (Jabbar, et al., 2015). Although vouchers and tax credits can be debated on several fronts, researchers from a 2007 study of vouchers by RAND and a 2015 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research have suggested key design safeguards for those states still wishing to proceed with one of those privatization options:

- Target vouchers to students who are considered at-risk.

- Require open admissions from participating private schools.

- Provide incentives for private schools to admit special needs students.

- Require participating private schools to set tuition at exactly the voucher value.

- Ensure all parents receive clear and timely information about voucher options.

Segregative Effect of Vouchers and Tax Credit Programs

Although school privatization advocates often allude to the expanded options available through vouchers and privatization programs, like tax credits, the research shows that these programs tend to increase racial segregation. The risk of racial segregation is especially potent where privatization laws do not have adequate protections built into the law (Mickelson & Southworth, 2008). This should be very concerning for policymakers because decreased racial segregation has been found to benefit both minority students and White students academically, socially and emotionally (Seigel-Hawley, 2012).

Studies finding segregative effects based on race and socioeconomic status include:

- A 2007 review of Florida’s voucher and tax credit programs by Harris, Herrington & Albee found strong evidence of increased school racial segregation.

- A 2007 study by Huerte & d’Entremont of Minnesota’s tuition tax credit program suggests that tuition tax credits did not significantly impact school competition, as lower-income families tended not to claim the credits as frequently as already higher-income families.

- A 2009 study by Meléndez of Arizona’s Education Tax Credit program concluded that it exacerbated educational inequities since students eligible for free and reduced-price lunch were significantly less likely to benefit from ETC usage and funding.

Charter Facilities

The Texas legislature created charter schools in 1995, in part, to improve student learning and to encourage different and innovative learning methods (TEC § 12.001). After 20 years of the Texas charter school “experiment,” the results show that student learning has not improved as a result of charter schools. According to the 2016 TEA accountability ratings:

- Nearly one out of every 10 charter operators (9.8 percent) received “Improvement Required” ratings compared to only one out of every 25 public school districts (3.8 percent).

- Nearly one out of every four charter campuses (29.9 percent) failed to achieve the “met standard” or the lower “alternative standard,” or were not rated compared to fewer than one out of every 10 public school campuses (10.5 percent).

These results are relatively consistent over the last four years (See 2016 TEA Accountability State Summary, https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/account/2016/statesummary.html).

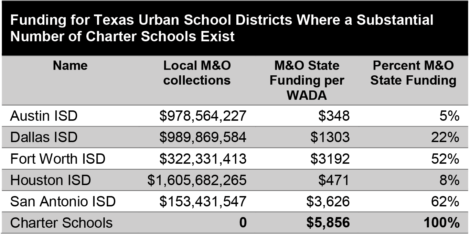

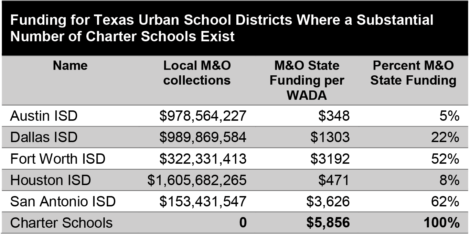

In spite of the dismal performance of charters, over the last 10 years, the Texas Legislature has increased its funding for charter operators from $200 million to over $2 billion. Because charter operators have no local tax bases, the state must provide 100 percent of funding for maintenance and operations (M&O). This contrasts to the state providing only between 5 percent and 62 percent of funding for Texas urban school districts located in the cities where a substantial number of charter schools exists (estimates based on TEA spreadsheet produced September 2016).

Recommendation:Based on these analyses and other studies of charter school performance, SB 2’s allocation of $60 million for charter schools does not appear to be a wise investment.

Facilities Funding for Traditional Public Schools

While investment in charter school facilities and funding is off target, the State could wisely increase funding for traditional public school facilities. A study by IDRA’s Jose A. Cardenas School Finance Fellow examining the factors contributing to expanded state investment in equitable public school facilities in five states, including Texas, found that the state’s share of facilities funding among the lowest in the country (Rivera, 2017; available at http://budurl.com/IDRAsffFR).

According to a 2016 report, Texas’ state share of capital outlay was only 9 percent ($12.21 billion), between 1992-93 and 2012-13, compared to a national average of 18 percent (Filardo, 2016). This lack of investment results “primarily from highly variable local property wealth and not subject to recapture, the amount local districts can individually raise varies substantially. Second, the State of Texas has historically been tax-averse and collects less tax revenue per capita than many other states and less than any other case study state (Lee, et al., 2015), which affects the state’s ability to spend on programs.”

In addition, equity differences between high-property wealth and low-property wealth remain a critical challenge for the state. According to the IDRA study, “In 2016, the lowest quintile of school districts by property wealth taxed themselves an average of 23 pennies, resulting in $45.40 of total I&S revenue per student per penny of tax effort. However, the fourth quintile of school districts w[as] able to tax themselves at approximately the same rate (22 pennies) and raise $61.74 per student per penny of tax effort.” Consequently, the increase in EDA funding for school districts from $35/ADA to $40/ADA under SB 2 could not expected to result in much of a difference.

Recommendation: The $60 million cap on new monies also will not make much of an impact, especially given the tremendous need by aging schools and fast growth school districts. Instead, the state should consider increasing EDA to at least $60/ADA and removing the cap on new monies.

Hardship Exemption

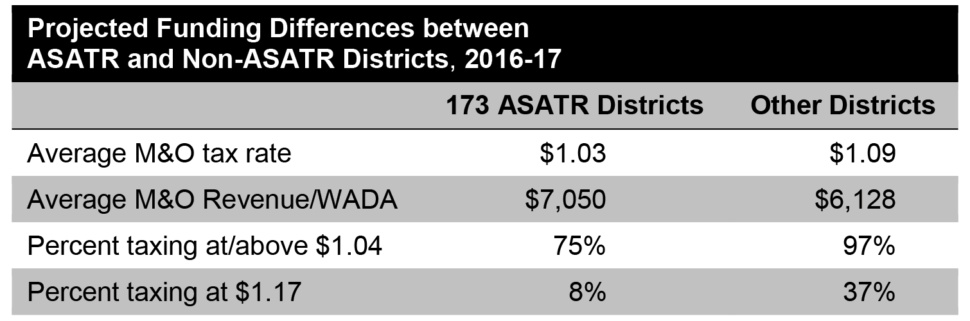

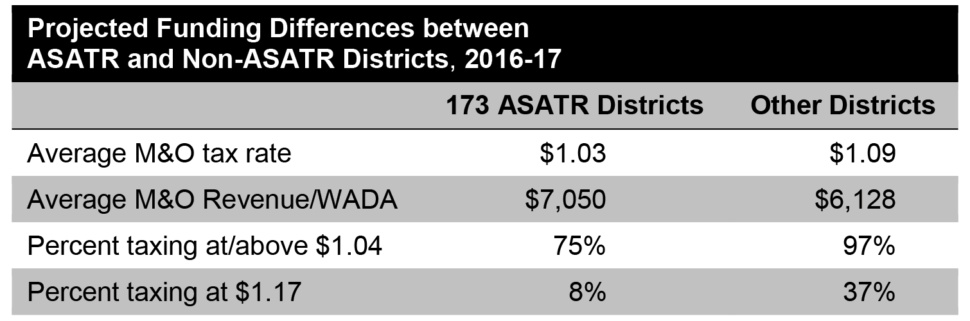

The “hardship exemption” noted in SB 2 also is troublesome for equity. Additional State Aid for Tax Relief (ASATR) is a hold-harmless measure that has exceeded its temporary purpose. The hardship exemption will merely be “ASATR-lite,” operating as the next iteration of the hold-harmless measure.

Several remaining ASATR districts continue to benefit greatly from ASATR payments, operating as tax havens. IDRA and doctoral candidate Madeline Haynes analyzed projected data in TEA spreadsheets produced in the fall of 2016 for TLEC. Key findings of the analysis of ASATR funding show the following:

- Estimated total amount of ASATR for 2016-17: $220,262,853

- The number of districts receiving ASATR has fallen from a high of 1,022 in 2007 to 173 projected in 2016-17.

- 102 of the 173 ASATR districts are ranked in the two highest deciles of property wealth/WADA and they are projected to receive $120,609,260 compared to only eight districts in the lowest two deciles receiving $6,542,080.

- Districts receiving ASATR range from $4.92 in ASATR/WADA to $5,007.43 ASATR/WADA. The mean is $814 ASATR/WADA.

- Tax rates also range significantly for ASATR districts, from $0.71 to $1.17.

- The property wealth/WADA ranges significant for districts receiving ASATR, from $4,657/WADA to 14,554/WADA.

Recommendation: To avoid continuing inequities, IDRA recommends that the state eliminate all hold-harmless measures. In the alternative, if the “hardship exemption” transition program continues, it should prioritize lowest wealth districts with less revenue first, rather than the current pro rata share. In addition, it should not be available for those school districts that received ASATR and generated revenue well in excess of the statewide average M&O yield per penny.

IDRA thanks this committee for the opportunity to testify and stands ready as a resource. If you have any questions, please contact IDRA’s National Director of Policy, David Hinojosa, at david.hinojosa@idra.org or 210-444-1710, ext. 1739.

References

Belfield, C. (April 2016). Review of the School Choice Voucher: A “Get Out of Jail” Card? (Boulder, Colo.: National Education Policy Center. http://nepc.colorado.edu/thinktank/review-school-choice

Brief for Nevada State Education Association and the National Education Association as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, Schwartz v. López, 15-OC-00207-1B (2016) (no. 69611), Doc 2016-10539.

Carnoy, M. (February 28, 2017). School Vouchers Are Not a Proven Strategy for Improving Student Achievement (Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute). http://www.epi.org/files/pdf/121635.pdf

Cortiella, C., & S.H. Horowitz. Horowitz. (2014). The State of Learning Disabilities: Facts, Trends, and Emerging Issues (New York, N.Y.: National Center for Learning Disabilities). https://www.ncld.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/2014-State-of-LD.pdf

Education Research Alliance for New Orleans. (April 20, 2016). Is There Choice in School Choice? (New Orleans, La.: Education Research Alliance for New Orleans). http://educationresearchalliancenola.org/publications/is-there-choice-in-school-choice

Figlio, D.N. (August 2014). Evaluation of the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program Participation, Compliance and Test Scores in 2012-13 (University of Florida Northwestern University and National Bureau of Economic Research). https://www.stepupforstudents.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/ftc_research_2012-13_report.pdf

Filardo, M. (2016). State of Our Schools: America’s K-12 Facilities 2016 (Washington, D.C.: 21st Century School Fund).

Gill, B., & Timpane, P.M., Ross, K.E., Brewer, D.J., Booker, K. (2007). Rhetoric Versus Reality – What We Know and What We Need to Know About Vouchers and Charter Schools (Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation). http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1118-1.html

Gulosino, C., & Liebert, J. (2012). Review of “The Way of the Future: Education Savings Accounts for Every American Family” (Boulder, Colo.: National Education Policy Center). http://nepc.colorado.edu/thinktank/review-ESA

Harris, D.N., & Herrington, C.D., Albee, A. (January 1, 2007). “The Future of Vouchers: Lessons from the Adoption, Design, and Court Challenges of Florida’s Three Voucher Programs,” Educational Policy, Vol 21, Issue 1. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0895904806297209?journalCode=epxa

Huerta, L. A. & d’Entremont, C. (2007). “Education Tax Credits in a Post-Zelman Era: Legal, Political and Policy Alternative to Vouchers?,” Educational Policy, January/March 21(1), 73-109.

Jabbar, H., Holme, J., Lemke, M.A., LeClair, A.V., Sanchez, J., Torres, E.M. (2015). Will School Vouchers Benefit Low-Income Families? Assessing the Evidence (Austin, Texas: Texas Center for Education Policy, University of Texas at Austin). https://www.edb.utexas.edu/tcep/resources/TCEP%20Graduate%20Seminar%20DRAFT%20Vouchers%20Memo.pdf.

Lee, C., Pome, E., Beleacov, M., Pyon, D., & Park, M. (2015). State Government Tax Collections Summary Report: 2014 Economy-Wide Statistics Brief: Public Sector (Washington, D.C.: United States Census Bureau). http://www2.census.gov/govs/statetax/G14-STC-Final.pdf

Lubienski, C., & Brewer. T.J. (June 29, 2016). “An Analysis of Voucher Advocacy: Taking a Closer Look at the Uses and Limitations of ‘Gold Standard’ Research,” Peabody Journal of Education, Vol. 91, Issue 4, pp 455-472. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0161956X.2016.1207438

Meléndez, P.L. (2009). “Do Education Tax Credits Improve Equity?,” dissertation (The University of Arizona). http://arizona.openrepository.com/arizona/bitstream/10150/194044/1/azu_etd_10499_sip1_m.pdf

Mickelson, R.A., & Bottia, M., Southworth, S. (2008). School Choice and Segregation by Race, Class, and Achievement (Boulder, Colo.: National Education Policy Center). http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/school-choice-and-segregation-race-class-and-achievement

Müller, E., & E. Ahearn. (April 2007). Special Education Vouchers: Four State Approaches (Alexandria, Va.: National Association of State Directors of Special Education). http://nasdse.org/DesktopModules/DNNspot-Store/ProductFiles/190_954be661-ad13-4984-86ee-27ebbae0e49b.pdf

Rivera, M. (2017). What about the Schools? Factors Contributing to Expanded State Investment in School Facilities (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association). http://budurl.com/IDRAsffFR

Robledo Montecel, M., & Goodman, C. (2010). Courage to Connect – A Quality Schools Action Framework (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association). http://www.idra.org/change-model/courage-to-connect/

Rouse, C. E., & Barrow, L. (2009). “School Vouchers and Student Achievement: Recent Evidence, Remaining Questions,” Annual Review of Economics, 1(1), 17-42. http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.economics.050708.143354

Siegel-Hawley, G. How Non-Minority Students Also Benefit from Racially Diverse Schools, Research Brief (Washington, D.C.: National Coalition on School Diversity, October 2012). http://www.school-diversity.org/pdf/DiversityResearchBriefNo8.pdf

Witte, J.F., & Wolf, P.J., Carlson, D., Dean, A. (February 2012). Milwaukee Independent Charter Schools Study: Final Report on Four-Year Achievement Gains (School Choice Demonstration Project, Department of Education Reform, University of Arkansas, 201 Graduate Education Building). Fayetteville, Ark. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED530068.pdf

The Intercultural Development Research Association is an independent, non-profit organization led by María Robledo Montecel, Ph.D. Our mission is to achieve equal educational opportunity for every child through strong public schools that prepare all students to access and succeed in college. IDRA strengthens and transforms public education by providing dynamic training; useful research, evaluation, and frameworks for action; timely policy analyses; and innovative materials and programs.