• by Melivia Mujia • IDRA Newsletter • August 2019 •

How is it that we don’t hear the same concern from many adults complaining of poorly-run schools? Mostly, it’s not their fault. When a student has opinions regarding the schools, they are quick to be shut down by faculty. Their voices are silenced before anyone else can hear. Students are taught to have an opinion, but when it is opposing the general outlook, it usually is not liked.

But my school, South San Antonio High School, is different. When saw I injustices regarding LGBTQ issues, student counseling and disciplinary actions, I formed a student club to fight back. We reached out to Fiesta Youth, a non-profit organization that serves LGBTQ teens, young adults and their allies in San Antonio. With the principal’s approval, they provided information and gave sensitivity training to staff and faculty about LGBTQ issues so teachers could be aware of their hurtful comments and so they would respect the pronouns of a transitioning girl being picked on by faculty.

Then we saw a trend in students dealing with depression and anxiety. Our school counselors weren’t sufficiently trained to help. We talked to Communities In Schools. They provided social workers and therapists to help students transition from high school into college and help them with the issues they faced, whether financial, domestic or educational.

We also brought up the idea of getting a teen center for students to have a safe space where we would have counselors specifically there to help students if they had any issues regarding anxiety, depression or bullying. We realized there aren’t sufficient mental health facilities in our part of town. The closest places students could go to were downtown, which can be two hours away by bus. We worked with our city councilman for three years to get a $10 million grant for wrap-around services. We’re still working on that project.

We saw there was a noticeable number of students who were getting detention and suspension in an endless cycle. We researched groups in our community, and we set a goal to get help. We found El Joven Noble, an indigenous-based, youth leadership development program. We worked with them to take action for students to be able to provide community service and develop stronger self-awareness and confidence, so they wouldn’t be stuck in the school-to-prison pipeline.

It may be racism, environmentalism, LGBTQ and gender equity, human rights or social justice – each can be a focus of important student activism. Although the civil rights movement began more than half a century ago, racism and a lack of diversity continue to be issues on campuses across the country. And the concept of “going green” by enacting environmentally-friendly and sustainable policies has been discussed on hundreds of campuses in recent years. Generally, the wide-ranging concept of social justice that is concerned with any mistreatment of an individual by society may, for students, relate to mistreatment by the school administration.

The benefits of students becoming activists are that they learn how to speak publicly, do research, form their identities, and even learn how government and school policies work. They can learn how to organize events, get in touch with important people, and create strong bonds to continue to bring awareness to their issues.

Activism is a way for students to apply academic skills in a real-life context, proving that they have a well-rounded education. Research shows that students’ strong sense of engagement or attachment to their school leads to a decrease in the likelihood of their school failure and dropping out.

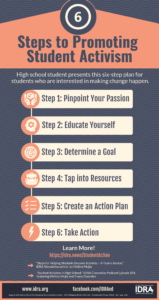

Step 1: Pinpoint Your Passion

Whether it’s fighting for LGBTQ equality, researching immigrant rights resources or helping beautify the school, the most important thing is to identify a cause that makes you get up in the morning believing you can make things better.

Step 2: Educate Yourself

Depending on your interest, there likely is an existing related organization. Before you go right in, do a little research to make sure you fully understand the issue. To be unbiased with information, try reading some position papers from groups from opposing viewpoints. Once you have a firm grip on the issue, you can see if you can commit to a strategy for change or need to adopt a different approach.

Step 3: Determine a Goal

When you start making others aware of the injustice you’ve identified, what action are you hoping to encourage? Listing short, intermediate and long-term goals keeps you organized and shows supporters you’ve thought things out. The club at my school keeps a spreadsheet that lists different topics with goals for each week, month, semester and year.

Step 4: Tap into Resources

Activists looking for strength in numbers should start on their school campus, preferably by reaching out to a faculty or staff member who will advise you. But don’t shy away from contacting national groups. Many have toolkits filled with media strategies and organizational plans.

Step 5: Create an Action Plan

Think about the objectives that need to be in place to achieve that goal. Then develop detailed action steps to complete the objectives and meet your goals. In the spreadsheet our club created, we list the different skills each student has, and we choose committees based on that. For example, the students on our writing committee write all the emails and papers we need.

Step 6: Take Action

Common methods of student activism are Internet activism, petitions, media outreach, boycotting, protests, school board presentations, sit-ins, demonstrations, occupations and civil disobedience. Sometimes you can make change just by alerting school leaders of an issue and offering possible solutions.

![]()

![]()

Melivia Mujia is a recent high school graduate from San Antonio and served as an IDRA summer intern.

[©2019, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the August 2019 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]