By Terrence Wilson, J.D., & Chloe Latham Sikes, M.A. • March 6, 2020 • See PDF version

School districts are more likely to be healthy when they are well-funded, attract and retain a diverse certified teacher workforce, engage families and communities meaningfully, and promote diversity and racial equity among students and staff. But, the practice of state officials taking control over school districts they believe are failing compromises the health of those districts and communities.

Struggling districts or school boards should be addressed through community-driven democratic processes and with state supports, not by removing local governance.

This issue brief reviews the historical background of state takeover policies and why they present problems for equitable education. We then discuss two legal case studies of public school districts that are currently in different phases of state takeovers, and the research on the state takeovers of local school districts as education policy reforms for student achievement. We conclude by presenting alternate policy recommendations that promote equity and student success.

Historical Overview of State Takeovers of Local School Districts

State laws authorizing takeovers began to appear in the 1970s and took off in the 1980s as much of the federal education oversight established in the 1960s was dissolved back to state control. A new focus on school accountability and standardized testing facilitated this shift. As of 2017, 33 states had passed laws to permit the state takeover of public school districts that did not meet the state’s accountability measures. Often, such districts are designated with a “turnaround” accountability status.

New Jersey enacted the first state takeover of a public school district in 1989 by taking over the Jersey City Public Schools. Since then, over 22 state governments and agencies have taken over more than 100 local public school districts across the country (Morel, 2018, p. 2).

Many state takeovers of school districts are justified as a response to low accountability ratings, which often rely on standardized testing performance, events, such as a natural disaster (in the case of New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina), or other district actions, including allegations of fiscal mismanagement. Many state laws confer power for the takeover to either the state education commissioner or state superintendent, the state board of education, or the local mayor. In Texas, for example, the law authorizes the commissioner of education to take over a school district under specific stipulations.

Why State Takeovers Are a Problem

While the reasons for a state takeover of a public school district often focus on declining academic achievement and fiscal mismanagement, studies show that state takeovers do not lead to increased academic achievement (Wong & Shen, 2005; Zimmer, Henry, Kho, 2017) and even further destabilize the school district (Harris, 2019; Morel, 2018). This turmoil can result in greater teacher and staff turnover in the district (Greenblatt, 2018), and exclusion of parent and community engagement in district decision-making (Morel, 2018).

For example, in the Detroit Public Schools, Michigan state officials placed the district under control of an emergency manager for 17 years (1999-2016) and left it arguably worse off than before. A report of the state’s management of the district found that there was an estimated $610 million in wasteful spending and rampant mismanagement of the district’s schools and educational services to students (DPS Report 2016).

Similarly, in Tennessee, public school districts that were controlled under a state turnaround strategy had the same or worse outcomes than reform strategies that maintained local control (Zimmer et al., 2017).

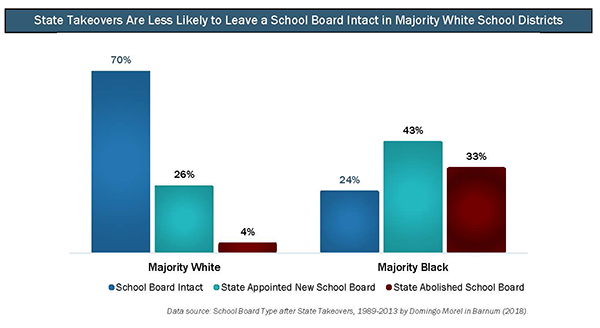

Moreover, state takeovers as a reform strategy tend to exacerbate racial segregation within a district community (Harris, 2019; Morel, 2018). About 85% of state takeovers across the country affect majority Black and majority Latino school districts (Morel, 2018). School districts governed by and serving a majority Black population are 11 times more likely to have the local school board abolished by the state than majority White-serving districts (Morel, 2018).

Sample Legal Cases

Two current cases of school districts under state control illustrate the harmful and lasting effects of state takeovers.

Houston Independent School District

On November 6, 2019, one day after the election of several new school board members, the Texas Commissioner of Education notified the Houston Independent School District (ISD) that it was slated for state takeover. The notification included the commissioner’s plans to abolish the elected school board to appoint a board of managers in its place. The state’s justification for the takeover hinged largely on the persistently low accountability rating of a single school campus, despite the overall district’s passing rating in the accountability system (the district has more than 280 schools). In response to the campus’ low rating, the commissioner lowered the accreditation status of the entire district, which the state alleges provided the grounds for takeover actions.

The Houston Federation of Teachers and other plaintiffs filed a lawsuit in federal court and requested a preliminary injunction to stop the state agency from taking over the district. Among other claims, the plaintiffs argued the commissioner’s takeover so soon after an election violated the Voting Rights Act and the district’s right to due process. The federal court denied the injunction and dismissed the plaintiff’s federal claims, but the teacher and voter groups were successful in a lower state court. In January 2020, they won an injunction against the state’s appointment of a board of managers. The district court judge decided that the commissioner’s actions against Houston ISD exceeded the authority given to him under the Texas Education Code. At the time of writing, the case is scheduled to be tried in June of 2020.

Little Rock School District

The Little Rock School District has been under state control since 2015. The Arkansas State Board of Education initially dissolved the school board and appointed the Arkansas Education Secretary to run the district due to six school campus’s persistently low accountability ratings (the district has almost 50 schools). The schools in question served student populations that are predominately Black, which led to concerns about racial segregation in the state’s reform actions.

Advocates opposed to the takeover argued that it violated students’ constitutional rights under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (which allows people to sue the government for civil rights violations) due to the disproportionate racial impact of the takeover on students of color in the district. However, a federal judge ruled that discriminatory effects alone are insufficient to show discriminatory intentions.

Now, five years later, the state is handing control back to the local level in worse shape than when the district was taken over. English and math scores have not improved in the five years of state control, and eight campuses – up from the original six– now are labelled “underperforming.” Moreover, a proposed transition plan would have maintained state control over campuses that largely serve Black students and handed local community control back over to campuses that serve a greater proportion of White students.

Given Little Rock’s infamous school desegregation legacy, the state takeover and the patchwork transition plan that falls along racial lines alarmed the district community members and led to community and teacher resistance. The community is now in the throes of deciding how to make a successful transition that does not further fragment, or segregate, the district.

Policy Recommendations

IDRA promotes family and community engagement, supportive funding, a diverse and certified teacher workforce, racial and socioeconomic integration, and culturally-relevant practices as critical components to school district and campus health. Based on research, IDRA recommends the following alternatives to state takeover policies.

- States should adopt community-based turnaround efforts – instead of state takeovers or private partnerships – that support holistic, wraparound services to support schools that face multiple challenges. Evidence shows that community-based approaches enable grassroots changes to educational improvements.

- States should explore options that treat local districts as the democratic entities that they are intended to be. In the event of corruption or malpractice, districts can hold special elections to remove individuals from school boards. In the case of multiple special elections, a community advisory committee can help restructure and retrain new board members and district administrators.

- Families can join coalitions across school districts to advocate for new strategies and appropriate implementation that support their schools, maintain local governance and incorporate communities in district decision-making.

References

Barnum, M. (2018). “When states take over school districts, they say it’s about academics. This political scientist says it’s about race and power,” Chalkbeat. https://chalkbeat.org/posts/us/2018/06/12/state-takeovers-book/

Brantley, M., & Miller, L. (2020, March 2). “Little Rock School District Reports Mass Teacher Sickness Today,” Arkansas Times. https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2020/03/02/little-rock-school-district-reports-mass-teacher-sickness-today

Breen, D. (November 13, 2019). “As LSRD Approaches Five Years of State Control, Its Future is Still Uncertain,” KUAR NPR. https://www.ualrpublicradio.org/post/lrsd-approaches-five-years-state-control-its-future-still-uncertain

Bureau of Legislative Research. (September 10, 2019). Holding Arkansas Schools Accountable – Ensuring an Adequate and Equitable Education for All Students. https://237995-729345-1-raikfcquaxqncofqfm.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Handout-C1_AccountabilityReport-05.pdf

Doe v. Arkansas Dept. of Educ. (E.D. Ark. 2016) (Order No. 4:15-cv-623-DPM). Little Rock Order dismissing constitutional challenge to state takeover.

Greenblatt, A. (2018). “The problem with school takeovers,” Governing. https://www.governing.com/topics/education/gov-school-takeovers-newark-new-jersey.html

Harris, A. (2019, October). “An attempt to resegregate Little Rock, of all places,” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2019/10/little-rock-still-fighting-school-integration/600436/

Houston Indep. Sch. Dist. v. Tex. Educ. Agency (W.D. Tex. 2019). Houston Federal District Court Case.

Houston Indep. Sch. Dist. v. Tex. Educ. Agency. (459th Judicial District, Travis County, Texas, Cause No. D-1-GN-19-003695). Houston State District Court Order Granting Injunction.

Millar, L. (October 3, 2019). “LSRD ‘grades’ and the many flaws in the state’s education accountability system and how it’s being applied,” Arkansas Times. https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2019/10/03/lrsd-grades-and-the-many-flaws-in-the-states-education-accountability-system-and-how-its-being-applied)

Morel, D. (2018). Takeover: Race, Education, and American Democracy. Oxford University Press.

Pitchford, G.K. (November 8, 2019). Review of Detroit Public Schools During State Management 1999-20016. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6549951-Review-of-Detroit-Public-Schools-During-State.html#document/p1

Texas Education Code, §39A.001. Accountability Interventions and Sanctions, Interventions and Sanctions for School Districts. https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/ED/htm/ED.39A.htm#39A

Wong, K., & Shen, F.X. (2005). “When Mayors Lead Urban Schools: Assessing the Effects of Takeover.” In W. Howell (Ed.) Besieged. The Brookings Institution.

Zimmer, R., Henry, G.T., & Kho, A. (2017). “The Effects of School Turnaround in Tennessee’s Achievement School District and Innovation Zones,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(4), 670-696. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3102/0162373717705729