• By José L. Rodríguez, M.A. • IDRA Newsletter • June- July 2009

The demands to meet adequate yearly progress (AYP) have administrators and teachers looking for specific panaceas to solve problems associated with the lack of success in meeting student needs, particularly within diverse student populations.

Research tells us that students who value themselves and who feel valued and respected by their teachers are more likely to become academically engaged and successful in school. This article describes how IDRA’s coaching and mentoring approach can transform teacher expectations.

Ruth Schoenbach, Cynthia Greenleaf, Christine Cziko and Lori Hurwitz’s (1999) “Dimensions of Classroom Life Supporting Reading Apprenticeship” provides a framework, in this case, to define mentoring activities. Each of these dimensions must be strengthened to embody the importance of valuing and respecting cultural and linguistic differences in a diverse classroom.

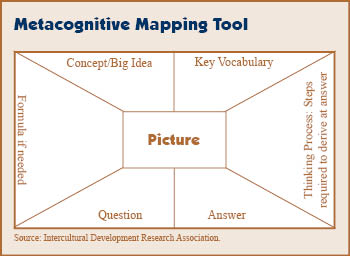

Staff at IDRA have developed a metacognitive mapping tool (see right) specifically designed to help English language learners focus on the use of graphics, key vocabulary, and thinking processes needed to decipher text or test questions.

Staff at IDRA have developed a metacognitive mapping tool (see right) specifically designed to help English language learners focus on the use of graphics, key vocabulary, and thinking processes needed to decipher text or test questions.

For several months, an IDRA consultant served as coach and mentor for one particular cohort of content area teachers. IDRA’s coaching and mentoring includes co-planning and co-teaching. Over time, the consultant established a relationship with the students and teachers. A safe environment was established. Students knew that, when the consultant was teaching, the class and everyone would be engaged in reading, writing, speaking and listening.

As the state testing dates come closer, it appears that teachers must think only about the test, leading them to focus on strategies to pass benchmark after benchmark to the exclusion of a rigorous curriculum.

For one particular school visit, the IDRA consultant prepared by completing a released version of the state test to experience what the students go through while taking the exam. The consultant – an English language learner himself – then analyzed and reflected on the questions. It had been a difficult task. Not only did students have to read and understand the question, they also viewed the illustrations with many questions and had to understand the images as well. There were several trouble spots that the consultant encountered. During the school visit, the consultant went into a classroom led by a teacher who had practically given up. She resisted trying new ideas. In her mind, only a few of her students would succeed anyway. The consultant relied on IDRA’s set of pedagogical principles, that permeate all IDRA activities, and particularly focused on IDRA’s Engagement-Based Sheltered Instruction (EBSI) model, to create a mentoring strategy.

Social Dimension of Classroom Life

According Schoenbach, et al. (1999), the social dimension is established by the teacher and students by creating an environment that is safe and conducive to learning. The social dimension enables students to practice what they are learning and to feel secure enough to make mistakes and struggle with the confusion that comes from not being able to understand the texts.

Teachers need to differentiate instruction by making modifications to ensure that their English language learners are actively engaged throughout the lesson regardless of their English language proficiency level (Villarreal, 2009).

In the classrooms at this particular school, the social dimension has been in place, and the students feel comfortable with everyone, including the IDRA consultant. No one is left out, and everyone participates in the lesson. Dr.

Abelardo Villarreal

</personname />(2009) states, “English language learners should be fully integrated into regular classroom instruction for at least 75 percent of the time.” At first, there were some students who did not want to participate. The consultant immediately identified them and assigned a role for them.

On the day of the site visit, students worked in small groups of three to four students each. Each group received a concept map and a picture from the sample state test. The students first were to list as many key words related to the picture that they could write down in two minutes. Students reviewed the list and identified the key concept or the big idea related to the key vocabulary. Each group then presented the key concept and the list to the rest of the class.

It is during these presentations that students get to experience and practice active listening. The IDRA consultant then asked the students to generate questions related to the key concept and the picture that they thought might be good test questions. One student stated, “We never get opportunities to write questions for a test, we only answer them.”

Personal Dimension of Classroom Life

The personal dimension described by Schoenbach, et al. (1999) enables students to use a wide range of metacognitive and cognitive strategies to make sense of the text.

The students felt empowered to write down their questions and to stand up in front of the class and explain why they generated such a question and give an answer with confidence and a sense of pride. The IDRA consultant then took the sample test questions and had the students read the questions that corresponded to their pictures. The students were amazed that the test questions were very similar to the questions they came up with. During the process of generating questions, the students were using a variety of cognitive strategies that they had already learned from past experiences.

The third dimension of the model described below focuses on adding cognitive strategies to their expanding repertoire. The metacognitive concept map that the IDRA consultant provided for the students is another tool to use while taking a test or in general learning. Students can jot down the steps of the map on the margins or on a piece of scrap paper.

One student pointed out that now she would have to “really pay close attention to the pictures in the test because they can be tricky.”

Cognitive Dimension of Classroom Life

The cognitive dimension enables students to use different strategies to skim through the text or simply view a picture and identify the big idea or key concept being taught. Students and the teacher monitor for comprehension to see if learning is occurring by having students paraphrase or summarize what has been taught.

It was gratifying to see the teacher glance over and smile at the IDRA consultant as if saying, “I’ve taught them well!” It was interesting to observe the students’ problem solving to ensure that their questions captured the essence of the picture and that the questions would match the objective being taught.

Students were successfully engaged in the activity. Josie Danini Cortez states: “Successful engagement means there is no escape, no excuse, no exit for any student. It means that as a teacher, administrator, faculty member or counselor, it is your job to convince each and every student that he or she matters, that they have something valuable to contribute to their school and their community” (2009).

After the activity, the students felt as if they had contributed to their own education and to the instruction.

Knowledge-building Dimension of Classroom Life

The fourth dimension is the knowledge-building dimension where the students build their understanding of the content and expand their schemata. Through the activity that the IDRA consultant was conducting, the students were using their prior knowledge to participate in meaningful conversations that were relevant and helped them understand the world around them. The students were now able to understand their text because they were helping each other and contributing to their own knowledge rather than depending on a teacher-led lecture.

Metacognitive Dimension of Classroom Life

The fifth dimension is the heart of the model. All of the other dimensions are tied together with the metacognitive conversation dimension, “an ongoing conversation in which teacher and student think about and discuss their personal relationships to reading, the social environment and resources of the classroom, their cognitive activity, and the kinds of knowledge required to make sense of the text” (Schoenbach, et al., 1999).

The “Dimensions of Classroom Life Supporting Reading Apprenticeship” model was clearly observable in the classroom demonstration lesson. The combination of the model coupled with the EBSI model are beneficial for language development in sheltered instruction classrooms.

After the demonstration lesson, the teachers met with the IDRA consultant for a debriefing meeting. They were impressed at how much the students knew about the content. The teachers agreed that they learned that they must allow their students to contribute to their own knowledge by encouraging more meaningful conversations in their classrooms.

The English language learners were able to practice their second language in a safe environment. Their teachers had an opportunity to see that their English language learners do know and understand the concepts being taught. They just need an opportunity to use the language they are acquiring in a meaningful manner that is safe for them.

Resources

Cortez, J.D. “Engaging Ourselves to Engage Our Students,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, March 2009).

Schoenbach, R., and C. Greenleaf, C. Cziko, L. Hurwitz. Reading for Understanding: A Guide to Improving Reading in Middle and High School Classrooms (San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey-Bass, 1999).

Villarreal, A. “Ten Principles that Guide the Development of an Effective Educational Plan for English Language Learners at the Secondary Level – Part II,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, February 2009).

José L. Rodríguez, M.A., is a former education associate in the IDRA Field Services. Comments and questions may be directed to him via e-mail at feedback@idra.org.

[©2009, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the June- July 2009 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]