• by Karmen Rouland, Ph.D., Susan Shaffer and Phoebe Schlanger • IDRA Newsletter • June-July 2017 •

Editor’s Note: The IDRA EAC-South provides technical assistance and training to build capacity of local educators to serve their diverse student populations. The IDRA EAC-South is one of four regional equity assistance centers and serves Region II, which covers Washington, D.C., and 11 states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia. IDRA is working with staff at the Southern Education Foundation and the Mid-Atlantic Equity Consortium to develop local capacity in the region among the 2,341 school districts and 29,632 schools with over 1 million educators and 16 million students. More information is available at http://www.idra.org/eac-south/.

We collect data on students in all aspects of learning and teaching and throughout all parts of school operations. Data can indicate what teachers are teaching and what students are learning and can inform how we can improve teaching and other factors that influence learning.

We collect data on students in all aspects of learning and teaching and throughout all parts of school operations. Data can indicate what teachers are teaching and what students are learning and can inform how we can improve teaching and other factors that influence learning.

But collecting data does not always translate into using data. When data uncover low performance in schools, we hesitate to analyze it for underlying causes of achievement problems.

Educational equity gaps for all students persist, and an uncertainty looms about whether students are on-track for graduation and college entry. According to the most recent America’s Promise Alliance report, the national high school graduation rate is 83.2 percent (DePaoli, et al., 2017), an increase over the last five years. The remaining 16.8 percent, however, represent millions of students who do not graduate. In addition, gaps in graduation rates remain for students of color, students with disabilities, English learners and low-income students (DePaoli, et al., 2017).

We recommend using data to uncover truths about students’ academic performance and college trajectory, keeping in mind the following principles.

We recommend using data to uncover truths about students’ academic performance and college trajectory, keeping in mind the following principles.

- Principle 1: Measuring Equity Matters. Analyze the issues from an equity perspective by disaggregating data and examining outcomes for subgroups of students. Create SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, timely) and an action plan to monitor strategies to improve or sustain them.

- Principle 2: Honest Data Inquiry Matters. Acknowledge hard truths regarding outcomes. Members of the data team, including parents and community members, should work together to discuss reasons for the undesirable results by using the strategies and tools discussed in this article.

- Principle 3: Parents and Community Members’ Participation Matters. Parents and community members can become data gatherers and analysts as they conduct surveys, interviews and online research. Partnerships with parents and community organizations can help increase access to programs and strategies for improvements in student outcomes (Steinberg & Almeida, 2010).

Research suggests that students who are on track academically at the end of their ninth grade year are three times more likely to graduate from high school than students who are off track (Allensworth, 2013). Factors associated with being on track for graduation and postsecondary success are credit accumulation and course performance, attendance, and behavior (Hazel, et al., 2014; Hoover & Cozzens, 2016; Steinberg & Almeida, 2010).

Students need access to educators who have high expectations for their academic success and rigorous curriculum in order to develop skills, such as comprehension, computation and critical thinking, necessary for postsecondary success (Hazel, et al., 2014).

This article walks through three strategies for using data to help ensure that students are on track for high school completion, college entry, and college completion and success. The strategies include the following.

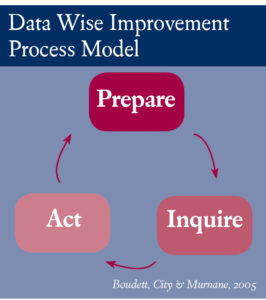

Prepare: Organize a team, determine the data you need and locate the data

The first step of any data-driven decision-making model is to organize a team that will be responsible for collecting and analyzing data. Data teams can take on many configurations: grade-level teachers, a mix of teachers and administrators, and/or guidance counselors, other support staff, parents and community members (Peery, 2011).

The first step of any data-driven decision-making model is to organize a team that will be responsible for collecting and analyzing data. Data teams can take on many configurations: grade-level teachers, a mix of teachers and administrators, and/or guidance counselors, other support staff, parents and community members (Peery, 2011).

The school or district’s student information system (SIS) or statewide longitudinal data system (SLDS) are reliable sources of student data. For data on college enrollment and persistence, teams can use the National Center for Education Statistics Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) and the National Student Clearinghouse data.

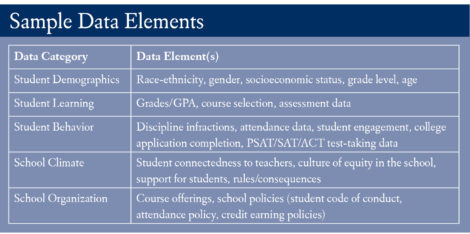

Most districts or states create data dashboards and data tools for educators to report patterns on certain topics. To ensure that educators have a robust picture of each student’s experience, data teams must collect data from several categories, such as student demographics, student learning, student behavior, school climate and school organization (Bambrick-Santoyo, 2010; White, 2011). For each category, teams must collect quantitative and qualitative data. The chart on Page 7 contains examples of each data category.

Once they have collected the data, teams should create a data inventory chart and ensure that the team has access to the data. Several examples of data inventory charts and other protocols may be found online at https://datawise.gse.harvard.edu/courses-and-materials.

Inquire: Dig deep and ask questions of student data

After creating and cataloguing data inventories, data teams should take a deep-dive to analyze data and conduct a root cause analysis to determine cause and effect relationships. One task is to conduct a SWOT analysis, where educators reflect on the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats associated with student data pertaining to the question, “Are my students on track for high school completion, college entry, and college completion/success?” If students are not on track for timely high school graduation, ask why.

Data teams can conduct SWOT analyses for individual students, student cohorts and student subgroups examining factors related to high school graduation and college-going. Evaluating this data creates knowledge through comparisons, relationships, patterns and trends, and it reveals inequities.

Download the one-page tool: Asking Questions of Student Data

Act: Create an action plan and monitor implementation of selected strategies

During the third and final phase of a “Data Wise Improvement Process,” data teams create action plans and develop a monitoring plan (Boudett, et al., 2005). Teams should incorporate SMART goals discussed above to ensure that strategies to improve or sustain outcomes are implemented with fidelity. In the action plan, list the task or action, responsible parties, targeted date for completion, and resources needed.

For many years, the research on data use and literacy tended to focus on the use of data for instructional improvement (Grissom, et al., 2017; New, 2016). While important (Boudett, et al., 2005), the goal of education is not just the completion of high school. As educators, we must prepare students to be college and career-ready. The policies and standards in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) and the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) make this imperative.

Resources

Allensworth, E. (2013). “The Use of Ninth-Grade Early Warning Indicators to Improve Chicago Schools,” Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 18(1), 68-83. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10824669.2013.745181

Bambrick-Santoyo, P. (2010). Driven by Data: A Practical Guide to Improve Instruction (San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass). http://www.uncommonschools.org/our-approach/thought-leadership/driven-by-data-book-paul-bambrick-santoyo

Boudett, K.P., City, E.A., & Murnane, R.J. (Eds.). (2005). Data Wise: A Step-By-Step Guide to Using Assessment Results to Improve Teaching and Learning (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Education Press).

DePaoli, J.L., Balfanz, R., Bridgeland, J., Atwell, M., & Ingram, E.S. (May 3, 2017). Building a Grad Nation: Progress and Challenge in Raising High School Graduation Rates – 2017 Annual Update (Washington, D.C.: America’s Promise Alliance). http://gradnation.americaspromise.org/report/2017-building-grad-nation-report

Grissom, J.A., Rubin, M., Neumerski, C.M., Cannata, M., Drake, T.A., Goldring, E., & Schuermann, P. (2017). “Central Office Supports for Data-Driven Talent Management Decisions: Evidence from the Implementation of New Systems for Measuring Teacher Effectiveness,” Educational Researcher, 46(1), 21-32. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3102/0013189X17694164?journalCode=edra

Hazel, C.E., Pfaff, K., Albanes, J., & Gallagher, J. (2014). “Multi-level Consultation with an Urban School District to Promote 9th Grade Supports for On-Time Graduation,” Psychology in the Schools, 51(4), 395-420. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pits.21752/full

Hoover, J., & Cozzens, J. (2016). “Dropout: A Study of Behavioral Risk Factors Among High School Students,” The International Journal of Educational Organization and Leadership, 23(4), 13-23.

New, J. (November 15, 2016). Building a Data-Driven Education System in the United States (Washington, D.C.: Center for Data Innovation). http://www2.datainnovation.org/2016-data-driven-education.pdf

Peery, A. (2011). The Data Teams Experience: A Guide for Effective Meetings (Englewood, Colo.: Lead + Learn Press).

Steinberg, A., & Almeida, C.A. (2010). “Expanding the Pathway to Postsecondary Success: How Recuperative Back-On-Track Schools are Making a Difference,” New Directions for Youth Development, 2010(127), 87-100.

White, S.H. (2011). Beyond the Numbers: Making Data Work for Teachers and School Leaders (2nd ed.) (Englewood, Colo.: Lead + Learn Press).