• by Albert Cortez, Ph.D., Josie Danini Cortez, M.A., and María Robledo Montecel, Ph.D. • IDRA Newsletter • September 2002 •

Arizona is losing almost one-third of its high school students from public school enrollment. Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) recently conducted a study of dropout-related issues in the state of Arizona, examining the numbers, costs, and programs that have been identified as effective in addressing the dropout issue. This article presents an overview of the study and key findings.

In October 2001, IDRA was selected by the Arizona Minority Education Policy Analysis Center (AMEPAC), a division of the Arizona Commission on Higher Education, to develop a commissioned paper focusing on the issue of dropouts in Arizona.

AMEPAC had a long-standing interest in the dropout issue, recognizing that non-graduation of substantial portions of the Arizona minority student population adversely impacted higher education enrollment prospects and had serious implications for many aspects of the Arizona economy.

Committed to helping inform public policy discussions on the issue, AMEPAC requested that IDRA assess the extent of the dropout problem in Arizona, develop estimates of the cost of dropouts to the state, identify existing dropout prevention programs, and develop a set of recommendations to address the issues identified.

Methods Used

In a 1986 study, IDRA developed a model for estimating the number and cost of dropouts in the state of Texas. The model was developed as part of a research project funded by the Texas Department of Community Affairs (TDCA), which later evolved into the Texas Department of Commerce, in collaboration with the Texas Education Agency (TEA). Using state- and county-level enrollment data, IDRA generated estimates of the number of students lost from enrollment (attrition), developing estimates for the overall high school student population, as well as for sub-groups of students by gender and race-ethnicity.

The original Texas model also provided estimates of the costs associated with dropping out, including costs related to job training and adult education, crime and incarceration, unemployment and job placement, and lost wages and related lost tax revenue.

The model has been used annually to estimate the costs of dropouts in Texas since 1986, with formulas adjusted to incorporate inflation experienced for each of the years of the study. With insights from years of experience in Texas, IDRA used similar procedures to develop attrition and cost estimates for Arizona.

In order to conduct its analyses, IDRA requested assistance from the Arizona Department of Education. The department was very cooperative in facilitating the acquisition of state- and county-level student enrollment data and prior dropout reports compiled by the state agency.

Major research strategies used in IDRA’s Arizona dropout study included:

- Reviewing Arizona Department of Education dropout studies and related data sets;

- Assessing costs of dropouts using available related data sources and conducting secondary analyses;

- Conducting attrition analyses using IDRA attrition estimation procedures;

- Reviewing related national dropout research; and

- Examining data on effective programs within and outside Arizona.

IDRA reviewed available data, tabulated attrition estimates, and interviewed staff of the Arizona Department of Education. IDRA also met with a cross section of Arizona’s public school educators, higher education leaders, business representatives, and Arizona Commission of Higher Education commissioners and staff. From this data, IDRA developed a report, “Arizona Dropouts: The Scope, the Cost and Successful Strategies to Address the Issue.” The report was published by AMEPAC.

Major Findings

Among the major findings in the report were the following:

- Arizona has a significant dropout problem with an estimated overall attrition rate of 33 percent.

- Arizona Department of Education procedures for calculating rates are better than procedures used in some other states.

- Caution is required in reviewing annual report data due to lack of data from some schools.

- Though some students indicate that they plan to drop out, most are identified as “status unknown.”

- The largest number of pupils who drop out do so in high school.

- As in most states, Arizona’s minority pupils drop out at higher rates than White pupils.

- Arizona loses hundreds of millions in lost wages and taxes because of its high dropout rates.

- Few Arizona dropout prevention programs have been rigorously evaluated.

Arizona’s Dropout Counting and Reporting Procedures

Reviews of department of education dropout reports, interviews with department of education staff, and work with the state’s student enrollment reports revealed that the department has made some effort to determine and validate the extent of school holding power throughout the state.

As part of its data collection and reporting process, the state requests that schools submit data on the enrollment status of their pupils. These procedures include instructions for reporting students’ status by specific categories, including a code for students whose status is unknown.

The Arizona Department of Education counts as dropouts students whose status is unknown, a procedure that provides a more accurate estimate of dropouts than one that excludes such pupils or treats them as a separate category of pupils that could be excluded from local or state dropout calculations.

Another strength of the department’s process is the decision to include in the dropout counting procedure students who have obtained or are in the process of acquiring a GED. In many states and at the national level, GED enrollees and graduates are not counted as dropouts – leading to inaccurate dropout counts.

While many of the Arizona Department of Education dropout counting and reporting processes are better than those in other states, two areas were identified as in need of improvement.

The first involved lack of data submission by some schools, a factor that led to the statewide reports suffering from missing data. Review of state reports did not make it clear how many schools had failed to submit their dropout data.

A second weakness in data submitted was an inability to conduct audits to verify the numbers that were submitted. Both of these issues were being addressed in legislation adopted by the state in 2001.

The more serious limitation of Arizona’s dropout reporting was its preference for calculating annual dropout rates rather than longitudinal, or cohort, dropout rates – considered a better measure of school holding power.

Though the state did conduct occasional graduation rate studies, lack of a comprehensive student tracking system hampered such efforts. A new student record system is expected to help the state develop improved cohort dropout rates in the future.

Attrition Rates in Arizona

To develop an estimate of Arizona school holding power, IDRA conducted an attrition study using procedures it developed and uses to estimate dropouts in Texas. IDRA’s attrition formula compares ninth grade enrollments with subsequent 12th grade enrollments for the same group. It provides the number and percentage of students who were enrolled in a particular year who are no longer “in the state system” three years later.

Using Arizona Department of Education enrollment figures, IDRA developed attrition estimates for the freshman classes of 1996, 1997, and 1998. The box below summarizes the statewide attrition rate for the three years analyzed.

In Arizona, the overall high school attrition rate was estimated at 21,233 pupils, or 32.8 percent, for the graduation class 1998; 21,422 pupils, or 32.8 percent, for the graduating class of 1999, and 21,472 pupils, or 31.8 percent, for the graduating class of 2000.

Attrition rates varied extensively by racial and ethnic group. Native American students, Hispanic students and African American students had much higher attrition rates than White students or Asian students.

Attrition rates for Native American students ranged from 48.3 percent for the class of 2000 to 45.3 percent for the class of 1998. Attrition for Hispanic students ranged from 44 percent for the class of 1999 to 42.7 percent for the class of 2000.

The “within group” attrition percentages were highest for Native American students, but because Hispanic students make up a larger proportion of the overall population of students in Arizona, they accounted for the larger number of students lost to attrition. Hispanic students comprised 8,629 of a total of 21,321 students lost to attrition for the 12th grade class of 1998; 8,824 of 21,465 students lost from the class of 1999; and 8,924 of the 21,551 students lost from the class of 2000.

Cost of Dropouts to Arizona

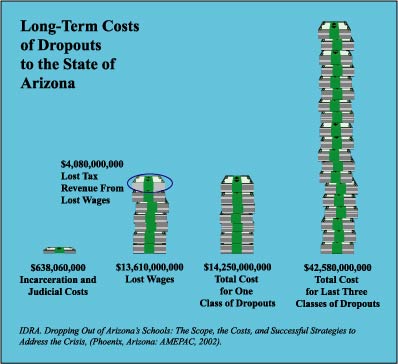

Using its Texas study as a starting point, IDRA developed cost estimates for incarceration, lost wages and lost tax revenue that would result from the loss of the estimated number of pupils derived from our attrition estimates. Those costs are outlined below.

Total annual costs attributable to one class of dropouts were estimated at $214.9 million. Cumulative costs over the working lifetime of that one group of dropouts totaled $14.25 billion. Adding all costs for the 64,117 students lost from the three classes analyzed yielded a staggering $42.58 billion in lost revenues.

By contrast, for every $1 Arizona spent on keeping those same pupils in school up to and through graduation would have yielded the state $66 in savings, not even considering how much more might have been gained if even 10 percent of those students lost had gone on to college.

Dropout Prevention and Recovery Efforts

In 1986, IDRA’s landmark research study canvassed Texas for dropout prevention and recovery programs. A survey of all Texas school districts, community colleges, universities, service delivery areas and community-based organizations found the following:

- Ninety percent of the dropout programs in Texas reported having no evaluation data. (Program staff were often confused, embarrassed or even defensive when asked for evaluation data or reports.) Furthermore, program personnel lacked information about the type of data needed to adequately evaluate a dropout prevention and recovery program.

- No individual in any of the institutions surveyed was charged with coordinating program efforts.

- No standardization or uniformity in data collection methodology existed. Nor did there exist any centralized or accessible information on programs in the state much less across the country.

The same situations remain in Texas and can be found in Arizona almost two decades later – there is no one individual accountable for ensuring that students remain in school in a meaningful way and no centralized repository for programs and models that work to keep students engaged and valued in schools.

In 1997, Olatokunbo S. Fashola and Robert E. Slavin reviewed dropout prevention programs across the country and determined that only two, the IDRA Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program and Upward Bound, had rigorous evaluations that provided evidence of effectiveness (1998).

Another serious problem is the lack of research on school factors that contribute to students dropping out before graduating from high school. Most reports inaccurately conclude that student deficiencies (poor grades, lack of motivation, absenteeism, etc.) are the cause for dropouts, or they cite “family background factors” such as poverty, less educated parents, single-parent families, family mobility, English language proficiency, and race-ethnicity.

As a result, the programmatic responses are based on “fixing” the student rather than seeing what school characteristics contribute to a student leaving school – characteristics such as the lack of quality teaching, low expectations for certain students, lack of professional development, a lack of resources, non-credentialed teachers, and a lack of leadership.

A review of the types of programmatic responses clearly shows that the deficit model prevails. Many programs are add-ons to the school with no institutional changes, or they take the student out of the traditional school setting to an alternative one that focuses on the “at-risk” factors.

What Works in Dropout Prevention

IDRA’s research on strategies for reducing the dropout rate, based on a review of the research of effective dropout prevention strategies and IDRA’s experience over the last three decades, shows the following components are vital to successful dropout prevention:

- All students must be valued.

- There must be at least one educator in a student’s life who is totally committed to the success of that student.

- Families must be valued as partners with the school, all committed to ensuring that equity and excellence is present in a student’s life.

- Schools must change and innovate to match the characteristics of their students and embrace the strengths and contributions that students and their families bring to the classroom.

- School staff, especially teachers, must be equipped with the tools needed to ensure their students’ success, including the use of technology, different learning styles and mentoring programs. Effective professional development can help provide these tools.

These components are also grounded in seven philosophical tenets that IDRA developed over the many years of our work in dropout prevention:

- All students can learn.

- The school must value all students.

- All students can actively contribute to their own education and to the education of others.

- All students, parents and teachers have the right to participate fully in creating and maintaining excellent schools.

- Excellence in schools contributes to individual and collective economic growth, stability and advancement.

- Commitment to educational excellence is created by including students, parents and teachers in setting goals, making decisions, monitoring progress and evaluating outcomes.

- Students, parents and teachers must be provided extensive, consistent support in ways that allow students to learn, teachers to teach and parents to be involved.

Fulton provides a series of evaluative questions that can help educators decide if a model or program is appropriate and effective for their students (Williams, 1999).

They should ask:

- What well-documented evidence or results in student achievement exist;

- Tough questions about suggested reforms and those already in place;

- The intended goals of a strategy, and how one knows if they are achieved;

- How to measure progress throughout the program’s implementation and assess its impact;

- How to identify and apply corrective measures, if needed;

- How long to allow a program to operate before deciding whether to continue, expand, or abandon it;

Fulton also recommends using a combination of strategies that include well-researched approaches as well as cutting-edge ones. Whatever strategies are used, they should be part of a comprehensive, long-term plan that improves student achievement.

This plan must be firmly grounded in “valuing” principles and with the expectation that all students will not only learn but will achieve and graduate from high school. No dropout prevention program, even the most effective ones, will accomplish this.

What is needed is a paradigm shift in schools – from “dropout prevention” to “graduation.” Every student must be seen as a high school graduate, instead of someone at risk of dropping out.

When this shift occurs, educators develop and implement comprehensive, long-term plans that are geared to educate and graduate every child beginning at pre-kindergarten. With this in place, there is no need for a “dropout prevention or recovery program;” every school is expected to hold on to their students and graduate them, with the skills needed to succeed in the 21st century.

Resources

Fashola, O. and R. Slavin. Show Me the Evidence! Proven and Promising Programs for America’s Schools (Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Corwin Press, Inc., 1998).

IDRA. Dropping Out of Arizona’s Schools: The Scope, the Costs, and Successful Strategies to Address the Crisis, commissioned by the Arizona Minority Education Policy Analysis Center (Phoenix, Arizona: AMEPAC, 2002).

Williams, T.L. The Directory of Programs for Students At Risk (Larchmont, New York: Eye on Education, 1999).

Albert Cortez, Ph.D., is the director of the IDRA Institute for Policy and Leadership. Josie Danini Cortez, M.A. is the IDRA production development coordinator. María Robledo Montecel, Ph.D., is the IDRA executive director. Comments and questions may be directed to them via e-mail at feedback@idra.org.

[©2002, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the September 2002 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]