• IDRA Newsletter • September 2005

Excerpt from the IDRA publication, Minority Women in Science: Forging the Way

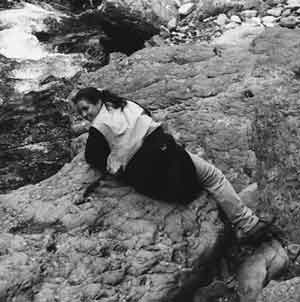

I was raised for the most part in Albuquerque, New Mexico. We had a ranch in Santa Rosa where we raised cattle to sell in a small meat market in Albuquerque. We spent a lot of time at the ranch, both for work and pleasure. We were always outside, riding horses, playing in the mud and hiking around the hills. I loved being at the ranch because it was so beautiful and fun. I loved riding horses and looking for pretty rocks. We were exposed to a lot of wildlife at a young age, and it made me appreciate how beautiful and diverse life is. I knew that I wanted to do something working with animals and wildlife.

I was raised for the most part in Albuquerque, New Mexico. We had a ranch in Santa Rosa where we raised cattle to sell in a small meat market in Albuquerque. We spent a lot of time at the ranch, both for work and pleasure. We were always outside, riding horses, playing in the mud and hiking around the hills. I loved being at the ranch because it was so beautiful and fun. I loved riding horses and looking for pretty rocks. We were exposed to a lot of wildlife at a young age, and it made me appreciate how beautiful and diverse life is. I knew that I wanted to do something working with animals and wildlife.

My parents got divorced when I was in middle school, and that period of my life was very difficult. I had a hard time focusing on school, and my grades definitely suffered. I did not know how to deal with my family breaking up. My older brother was so supportive of me and really helped me get through junior high and deal with what was happening at home.

I went to public schools through the eighth grade, then attended a private high school in Albuquerque. I had a wonderful science teacher in eighth grade who made science really fun and exciting. In high school, however, the school encouraged its graduates to pursue careers in business or engineering, rather than science. By this time, some of the hurt from my parents’ divorce had gone away, and I enjoyed my life at school much more. I was doing better academically, but I was not interested in business, unlike many of my classmates. My high school prepared me to go to college, but I did not know at the time that I would pursue science.

I went to New Mexico State for my undergraduate program. I did not know at first what I wanted to study. I knew I wanted to work with animals, maybe as a veterinarian. A friend suggested that I take a biology course, and I was amazed that I could have a career doing what I love: working outdoors with animals and wildlife. I received my Bachelor of Science degree in wildlife science. I am currently in a graduate program to get a master’s degree in wildlife science at New Mexico State University.

My brother and my father have always been supportive of my interest in and pursuit of science. My mother, on the other hand, has always thought that I should get married, stay home and have children. It was important to have the support of members of my family to challenge myself in school and to pursue science.

While my family and culture have supported my pursuit of science, it seems as though society assumes that only White men can become scientists, and that since I am neither White nor male, I should not even bother trying. I have to turn these negative prophecies into fuel to keep myself going. I am strong-willed, and when someone tells me I cannot do something, it is extra incentive to work twice as hard to prove them wrong.

These types of attitudes and barriers come up in school and at work. For example, many people are shocked at my interest in reptiles and amphibians. They do not believe a woman can handle picking up snakes and lizards. Sometimes others assume that I am not strong or intelligent, and these misguided assumptions have led them to look to other people, usually men, to get a certain job done. While this discrimination is wrong and hurtful, I have learned just to work hard in order to prove them wrong.

The most hurtful thing about discrimination is that it can make you doubt yourself. If someone else tells me that I cannot do something, there is a small voice in the back of my mind that agrees. If I just keep working hard, not only do I prove to others that I can do it, but more importantly, I also prove it to myself.

Sometimes discrimination can be subtle as well as overt. Some people have told me that I got admitted into school and got a job in science as an affirmative action “let-in,” just because I am Hispanic and because I am a woman. I set them straight immediately and retort, “I’m sure it has nothing to do with my 4.0 grade point average, four years of work experiences, and awesome references.” The important thing for me in combating discrimination or bias has been my conviction that I can succeed because of my talents and intelligence.

Sometimes it is helpful to have mentors along the way that provide guidance in terms of work or personal life. While my father and brother have been supporters, I have had mentors that I can go to for advice on my career or with questions about science in general. They taught me to be proud of who I am and helped me figure out how to attain my goals.

My mentor is an expert in the field of herpetology (the scientific study of reptiles and amphibians as a branch of zoology). I met him at a wildlife society conference in Arizona and have worked with him and others in the field since then. He supported me in my interest in studying reptiles and amphibians. What makes him great is that he makes learning fun and interesting (Yes, I am still learning even outside of school). I never feel dumb asking him a question. Finding a mentor can happen just by chance as mine did, or it can be through more formally designed programs. Many colleges have mentoring programs for students interested in science or math or many other disciplines. A little help can make a big difference.

As a wildlife biologist, I spend the majority of my time outside doing incredibly interesting research on wildlife. It is amazingly fun and very hard work. The bulk of my research centers on reptiles and amphibians, for example to determine population fluctuations. This means that we try to determine what makes the populations of certain species go up and down. We capture the animals, we measure, weigh and mark them, and then we release them in order to track their movements. Other research projects include detecting levels of contaminants (insecticides) in various mammals and conducting song bird surveys.

I have worked with endangered species such as the Mexican spotted owl, the Northern goshawk and the Southwestern willow flycatcher (birds). When one animal or species is lost forever (extinction), it has a significant impact on the food chain. An animal that feeds on the species that has become extinct has to find another food source, and the food that the extinct animal used to eat becomes overabundant. This is in addition to other changes in the environment and ecosystem that result when animals or plants become extinct.

What I love best about my job is that I am always outside in the sun with interesting wildlife. My coworkers also enjoy being outside doing research, and it is invigorating to be around people that love what they do.

While I love my work, I also enjoy traveling home to visit my family and friends. I like watching movies and hanging out with friends. In the spring and summer, I enjoy fly fishing. Most of my interests outside of work are related to work, since they involve being outdoors. How wonderful that my work life matches so perfectly with my personal interests.

This story was reprinted from Minority Women in Science: Forging the Way – Student Workbook published by IDRA.

Comments and questions may be directed to IDRA via e-mail at contact@idra.org.

[©2005, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the September 2005 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]