• by Paula Johnson, M.A. • IDRA Newsletter • September 2017 •

Numerous studies have confirmed the positive effects of preschool programs on future student achievement (NEA, 2017). Data from the latest census, however, reveals that only 64.2 percent of all 3-, 4- and 5-year-old children are being enrolled in preprimary programs (NCES, 2016).

Numerous studies have confirmed the positive effects of preschool programs on future student achievement (NEA, 2017). Data from the latest census, however, reveals that only 64.2 percent of all 3-, 4- and 5-year-old children are being enrolled in preprimary programs (NCES, 2016).

Studies have found many long-term benefits of preprimary education across three broad categories: (1) academics, (2) social skills and (3) attitudes toward school (Bakken, et al., 2017). In this article, I present the long-term academic and societal effects of high-quality early childhood programs, elements of high-quality programs, current enrollment trends among preschool-age children, barriers to enrollment and implications for public policy toward increasing participation.

Benefits of Early Childhood Education Programs

Researchers find preschool attendance is associated with increases in cognitive outcomes, such as school progress, high school graduation rates and post-secondary enrollment. They also show decreases in grade repetition and dropout rates (Barnett, 2008; Bakken, et al., 2017).

Gains in standardized test scores are a significant outcome in many research studies on preprimary education. A growing number of studies associate high-quality early childhood program participation with improved scores on tests taken at older grade levels (Bivens, et al., 2016). Early childhood programs also are credited with improving children’s social development, and reducing disruptive behaviors and the number of juvenile arrests (Bakken, et al., 2017; Bivens, et al., 2016).

The National Institute for Early Education Research endorses preschool programs that have been shown to benefit economically disadvantaged children and resulted in these long-term outcomes. Moreover, it has been found that students from all socio-economic backgrounds benefit from early childhood education (Barnett, 2008). Research also has attributed commitment to schooling, higher adult employment rates and earnings, and reduced adult crime and incarceration to participation in early learning programs (Schweinhart, 2013).

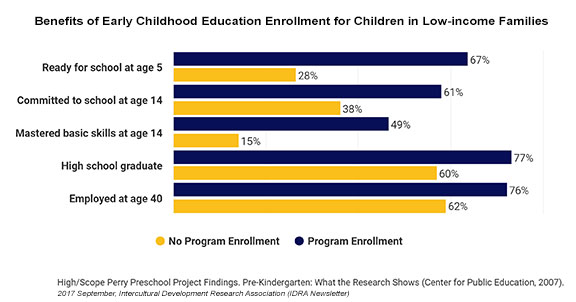

The High/Scope Perry Preschool Project found gains in student achievement as a result of participation in early childhood education programs (see chart below). The project revealed improved outcomes in each of five areas. Most notably, being school-ready by the age of 5 and having mastered basic skills at 14 showed the greatest impact. Students participating in preprimary education programs were 239 percent (2.4 times) more likely to be properly prepared for kindergarten. Even more impressive, students enrolled in prekindergarten centers were 325 percent (3.25 times) more likely to meet middle school requirements – an indicator for high school success. (Center for Public Education, 2007)

Defining High Quality

Early childhood programs must be staffed with adults well-versed in the social-emotional aspects and appropriate introduction of academic content of child development. Given the cultural diversity of students, it is important to note several characteristics that programs should strive for. For example, one exemplary school district has identified five key elements of an effective early childhood program: (1) Adults who are competent in the social-emotional aspects of child development as well as developmentally appropriate introduction of academic content; (2) Respect for the language and culture of the home; (3) Use of native language to support language and concept development; (4) Developmentally appropriate activities; and (5) Communication with and support for families (Montemayor, et al., 2016).

It is essential for early learning programs to nurture both the cognitive and social-emotional development of children to be successful (Bivens, et al., 2016). High-quality preschool centers require professionalized staff with credentialed teachers who achieve continuing professional development and engage in mentoring relationships (Barnett, 2008; Bivens, et al., 2016).

Research by IDRA showed how a seamlessly integrated instructional program with preschool and public school teachers can prevent children from encountering reading difficulties when they enter school. In IDRA’s Reading Early for Academic Development (READ) project, funded by the U.S. Department of Education, participating students’ standardized mean score on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III moved from 79 to 92 (Rodríguez, 2006).

Additionally, a quality curriculum is required to support student’s progress and guarantee that they are well-prepared to enter formal schooling environments (Barnett, 2008; Montes, 2016).Comprehensive programs like IDRA’s Semillitas de Aprendezaje combine a strong professional development component while building students’ literacy development through bilingual instruction (Montes, 2016). The curriculum reflects elements of Ellen Galinsky’s seven essential life skills every child needs to thrive as life-long learners and to take on life’s challenges. It also incorporates the Head Start early childhood competency indicators through literacy center activities that focus on listening and understanding, speaking and communicating, phonological awareness, comprehension, book knowledge and use, and print knowledge and emergent writing. (See Page 7.)

Preschool Family Landscapes

An important goal of preschool programs is to narrow the achievement gaps that occur between students from diverse races and ethnicities and family incomes. This gap begins to appear before students enter kindergarten and can widen as soon as age 5 or 6 (Bivens, et al., 2016).

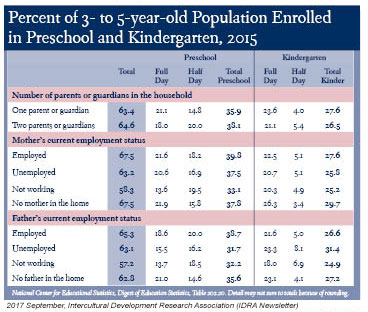

The United States is home to nearly 12 million 3- to 5-year-old children. Approximately 7,681,000 children in this age range are enrolled in some form of preprimary program. Enrollment is divided between preschool (37.4 percent) and kindergarten (26.8 percent). Most students (63.5 percent) are enrolled in full-time programs in either type of setting. (NCES, 2016)

Though most studies seek to investigate the benefits of a comprehensive preschool program for children from low-income families, data collected from the census do not provide parents’ income (see box above). Reports only indicate the employment status and number of guardians in the home to convey the economic circumstances of a child’s family. The percentages in the table indicate comparable participation across families, however, at 64.2 percent enrollment, there is a clear need for increased participation for all preschool-age children.

Barriers to Enrollment and Implications for Public Policy

Like educational gaps in achievement, there continues to be an investment gap in educational activities for preschool-age children due to disparities in income. Although there is a greater number of parents from lower-income households spending on these programs, the investment gap between high-income and low-income families continues to grow larger due to the rise in income inequality (Bivens, et al., 2016).

Limited access to high-quality preprimary learning centers has proven to be an added obstacle for parents seeking preschool education programs for their children (Barnett, 2008; Bivens, et al., 2016).

Public investment in quality prekindergarten education programs for children from poor families improves the education and health of the future workforce and produces significant social outcomes. In addition, such endeavors not only afford academic and social-emotional advantages, but they also increase future employment opportunities and earnings (Bivens, et al., 2016). Policies that establish a national investment of this nature would move us closer to equitable educational opportunities for the next generation.

For decades, early childhood education has been encouraged to promote increased academic success in later primary and secondary grades for students from families with limited financial resources. Unfortunately, inequitable access and opportunity block preprimary participation for many students from poor and even mid-income families.

Public investment in high-quality early childhood education produces significant effects on student achievement, in-grade retention, socialization, high school graduation and future income (Bakken, et al., 2017; Barnett, 2008). These studies provide evidence that early childhood programs greatly serve the social and academic needs of children as they enter the education system. Communities and school districts, working together, can ensure that cost, quality and access are no longer factors that dissuade parents from enrolling their young children in preschool programs. The benefits outweigh the cost and offer brighter futures for our youth.

Resources

Bakken, L., Brown, N. & Downing, B. (2017). “Early Childhood Education: The Long-Term Benefits,” Journal of Research in Childhood Education.

Barnett, W.S. (2008). Preschool Education and Its Lasting Effects: Research and Policy Implications (Boulder and Tempe, Ariz.: Education and the Public Interest Center & Education Policy Research Unit).

Bivens, J., García, E., Gould, E., Weiss, E., & Wilson, V. (2016). It’s Time for an Ambitious National Investment in America’s Children (Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute).

Center for Public Education. (March 2007). Pre-Kindergarten: What the Research Shows (Alexandria, Va.: Center for Public Education).

Montemayor, A.M., Casas, C., Medrano, B.A. & Gonzalez, A. (April 2016). “Bilingual Early Childhood Education – Capitalizing on the Language and Culture of the Home and Introducing English,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association).

Montes, F. (April 2016). “Three Signs that Your Pre-K Might Need a Make Over,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association).

NEA. (2017). Research on Early Childhood Education, web page (Washington, D.C.: National Education Association).

NCES. (2016). Digest of Education Statistics, Table 202.20 (Washington, D.C.: National Center for Educational Statistics).

Rodríguez, J.L. (May 2006). “Quality Professional Development Creates ‘Classrooms of Excellence,’” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association).

Schweinhart, L.J. (December 2013). “Long-term Follow-Up of a Preschool Experiment,” Journal of Experimental Criminology, 9(4), 389-409.

Paula Johnson, M.A., is an IDRA education associate. Comments and questions may be directed to her via email at paula.johnson@idra.org.

[©2017, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the September 2017 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]