By Morgan Craven, J.D. and Chloe Latham Sikes, Ph.D. • IDRA Newsletter • November-December 2022 •

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often called “the nation’s report card” is a federally-administered assessment given to a sample of students across the country. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reports the results, and last month released the 2022 scores for fourth and eighth grade students in reading and mathematics. These scores were the first released since 2019 and can be seen as one indicator of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and remote schooling on student learning.

The results show disturbing declines in reading and math across the country, with notable differences across student groups, including in Texas. Coupled with other critical information sources – like student, family and teacher surveys and other metrics of student learning and success – the NAEP scores support the need for additional investments in student learning, particularly for systemically-marginalized students disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and schooling disruptions (U.S. Department of Education, 2021). The scores also lead to important questions about student outcomes and how schools can better support all learners.

Policymakers, educators and researchers should continue to focus on the impact of investing resources into targeted interventions for systemically-marginalized students, data monitoring of COVID-19 relief and enhanced school-family-student engagement practices.

National and Texas NAEP Results

As anticipated given the three-year disruption to schools and student learning due to COVID-19, reading and math scores declined overall nationally. Since 2019, average math scores declined by 5 points among fourth graders and 8 points among eighth graders across the nation. This is the largest decline since the test was first administered in 1990.

Average reading scores declined by 3 points for fourth and eighth graders in the same time period. (NCES, 2022)

A closer look at disaggregated scores shows that these patterns are not evenly applied across all student groups. For example, while scores declined consistently across most racial groups in eighth grade math, there was not a statistically significant decline in the scores of eighth grade students of color in reading. Even with these differences, it is important to remember that overall score differences continue to reflect disproportionate educational opportunities for students of color compared to their white peers.

Learning progress in middle school, particularly in eighth grade, is indicative of high school preparedness and eventual college readiness (Allensworth et al., 2014). We examined the Texas eighth grade reading and math scores by race-ethnicity and emergent bilingual (English learner) status to see how students in middle school at the start of the pandemic fared as they now enter high school.

While we know that students experienced disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 based on their race and ethnicity, those patterns are not as clear cut in the data.

All Texas students experienced declines in math achievement according to NAEP.

Though math scores for white, Black and Latino students have been steadily falling for the past 10 years, there was a more dramatic drop between 2019 and 2022. The largest drop occurred in Asian and Pacific Islander students’ math scores, falling 10 points between the pre- and post-COVID testing years.

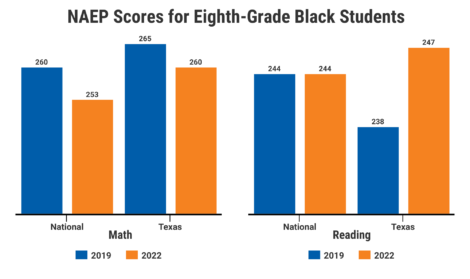

White students’ scores fell 9 points, students of two or more races fell by 6 points, Latino students’ scores fell by 7 points, and Black students’ scores fell by 5 points. The drop among groups resulted in narrowed racial gaps in scores.

Reading scores did not take the same dip as math scores though they still reveal the impact of learning disruptions during the pandemic. Interestingly, Black and emergent bilingual students made gains in their eighth grade reading scores between 2019 and 2022. Both groups also performed better in Texas than their national counterparts in reading.

What the Results Can Tell Us

While these scores do not provide a full picture of student achievement or learning disruptions over the past three years, they do offer two considerations for educators as they continue to develop and deliver learning recovery practices and to lawmakers considering ongoing investments in COVID-19 educational recovery.

First, investments in educational resources pay off. NAEP scores and questionnaires show that a greater percentage of higher-scoring eighth graders reported having more consistent access to learning resources than their lower-scoring peers. Such resources include digital devices like laptops, high-speed Internet access, school supplies, and real-time virtual learning with teachers (NCES, 2022).

Systemic inequities that impact access to these resources, like the digital divide and inequitable school funding, heightened the harms of the pandemic and have long contributed to unequal educational opportunities for communities of color and with low incomes.

Second, while test scores offer a useful snapshot of student learning, they do not offer explanations nor guidance toward learning recovery and student success. As learning recovery continues, federal, state and local actors should invest in evaluation systems to determine the factors that contribute to declines and gains in assessment scores and ensure they support effective programs and initiatives.

According to the NAEP, historically- and systemically-marginalized students, including Black, Latino and emergent bilingual students, experienced less dramatic declines and even some gains across the NAEP results.

While these results should not be seen as definitive and should be viewed alongside state-level assessments, these results could give us important information about state and school district outreach strategies, digital inclusion efforts, and adaptive learning initiatives and how those efforts may have made a dent in long-standing educational equities, as measured by the assessment.

This variance in NAEP results demonstrates that policymakers, practitioners and researchers should continue to focus on the impacts of investing resources into targeted interventions for systemically-marginalized students, data monitoring of COVID-19 relief and recovery efforts and enhanced school-family-student engagement practices.

Additionally, more research must be conducted on the results of the significant federal investments in education from the pandemic emergency relief distributed to states through the Elementary and Secondary Schools Emergency Relief (ESSER) fund. A deep examination of state and district relief fund priorities and investments could help to illuminate and bolster successful learning recovery strategies.

Given the limits of any single assessment, states and school systems should consider other metrics of student opportunity and success, such as safe school climates, sound asset-based pedagogies, student-family engagement, high-quality instructional materials, access and success in college, and greater digital inclusion and access.

Resources

Allensworth, E., Gwynne, J.A., de la Torre, M., & Moore, P.T. (November 2014). Looking Forward to High School and College – Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools. University of Chicago Consortium on School Research.

NCES. (January 12, 2022). National Assessment of Educational Progress, website. National Center for Education Statistics.

U.S. Department of Education. (June 2021). Education in a Pandemic: The Disparate Impacts of COVID-19 on America’s Students. U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights.

Morgan Craven, J.D., is the IDRA national director of policy, advocacy and community engagement. Comments and questions may be directed to her via email at morgan.craven@idra.org. Chloe Latham Sikes, Ph.D., is IDRA’s deputy director of policy. Comments and questions may be directed to her via e-mail at chloe.sikes@idra.org.

[©2022, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the November-December 2022 issue of the IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]