• By María “Cuca” Robledo Montecel, Ph.D., Albert Cortez, Ph.D., and Josie D. Cortez, M.A. • IDRA Newsletter • June- July 2007

Too many Texans are unable to get into college. Of those who graduate from high school, only one of five enroll in a Texas public university the following fall. Close to one of four enroll in a two-year college, but more than half will not enroll at all.

Too many Texans are unable to get into college. Of those who graduate from high school, only one of five enroll in a Texas public university the following fall. Close to one of four enroll in a two-year college, but more than half will not enroll at all.

Among those who do get in, many do not graduate. Thirteen out of 19 public universities in Texas graduate less than half of their students; six graduate less than a third.

In order to be economically competitive, Texas needs more college graduates. The state clearly needs more graduates from all groups, including low-income students and minority students, who are currently under-represented. They are more likely to face certain obstacles than are wealthier, non-minority students.

While not sufficient on its own, one strategy to increase access for minority students was adopted by the Texas Legislature in 1997 known as the Ten Percent Plan.

Under existing state legislation, any student enrolled in a public or private Texas high school is eligible for automatic admission to the state’s major public universities if the student is in the top 10 percent of his or her senior class. Developed partly in response to the Hopwood ruling prohibiting use of race- or ethnicity-based admissions factors, as well as rural legislators calling for expanded access for small high schools to the state’s elite public universities, the policy has sparked discussions from three major fronts.

The University of Texas at Austin asserts that the required acceptance of all Ten Percent Plan graduates has steadily decreased the number of admission slots that can be offered to other students.

A second set of critics has included a pool of primarily non-minority high schools in affluent areas that have seen the numbers of their students gaining admission to the flagship universities slowly declining over time. The loss of long-standing “unfettered” access and the efforts to regain their disproportionate entrees are claimed by the citing of higher test scores produced in these mostly affluent suburbs.

A third and smaller set of Ten Percent Plan critics cites studies conducted by the Harvard Civil Rights Project and others who conclude that while some “percent plans” may slightly improve the diversity of entering classes, the impact is not comparable to the access provided by earlier admission’s procedures that were struck down in the Hopwood case (but later validated by the recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the Gruder decision that allowed race to be considered as one factor in a multi-tiered admissions process). A related criticism of the Ten Percent Plan concept is that increases in the number of minority students impacted is too dependent on the existence of segregated high schools that often contribute to the new feeder patterns observed.

Several Texas legislators have filed plans to either totally eliminate the plan or to limit the number of students that may constitute the major universities’ entering freshmen class. Often, the claims of the effect of the Texas Ten Percent Plan are debated in the absence of objective student and school data, particularly data analyzed by non-university connected groups.

To help inform the debate this spring on the effects of the Texas Ten Percent Plan, IDRA compiled and analyzed available data on the students entering the University of Texas at Austin and all the Texas high schools that contributed graduating seniors to those incoming freshmen classes between the years of 1995 and 2006.

The summary that follows highlights our major findings on the issue. These findings were released on May 1, 2007. Detailed tables that were included in the brief are available online

Key Findings and Recommendations

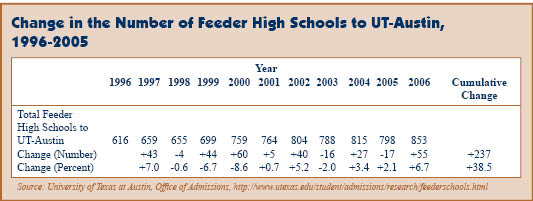

Finding #1: Since the adoption of the Ten Percent Plan, more Texas high schools have had their students enrolling at UT-Austin.

Recommendation: Mend it. Don’t end it. Given that the adoption of Texas’ Ten Percent Plan has contributed to a notable expansion of the number of Texas feeder high schools to UT-Austin, the policy should not be abandoned unless there is evidence of a proven plan that produces equal or greater increases in the number of high schools and students that have access to the university.

What the Data Say: Data obtained from the UT-Austin Office of Admissions indicate that the number of high schools enrolling freshmen at UT-Austin has increased from only 616 in 1996 (prior to adoption of the Ten Percent Plan) to 853 in 2006, a net gain of 237 high schools or 38.5 percent in 10 years.

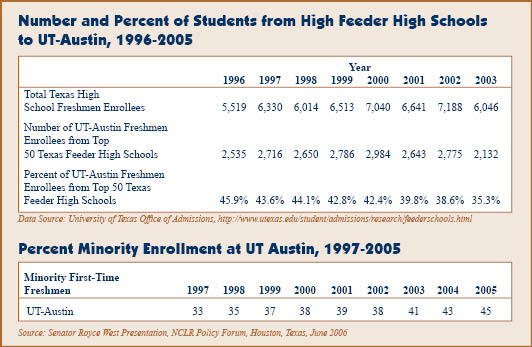

Finding #2: Despite the Ten Percent Plan, a small number of Texas high schools continue to account for a large percentage of freshmen enrolling at UT-Austin.

Finding #3: Texas feeder high schools with the largest number of freshmen enrollees also tend to have fewer numbers of low-income students.

Recommendations: Find out why a small subset of Texas high schools appear to be more successful at enrolling more students (possibly including more Ten Percent graduates) than most other Texas high schools and apply those lessons to historically underrepresented schools.

Money matters. Increase the number of scholarships and financial aid to low-income students enrolling at Texas universities.

What the Data Say: Analysis of UT-Austin feeder high schools from 1996 to 2003 indicates that a small number of Texas high schools continue to be overrepresented among Texas high schools enrolling freshmen students at UT-Austin. According to early research conducted by Dr. David Montejano prior to adoption of the Ten Percent Plan, about one half of all freshmen enrollees came from 54 Texas high schools, with 34 percent coming from 500 or more other high schools. In more recent analyses of the top UT-Austin feeder schools, IDRA found that the trend continues where 50 high schools in Texas persistently account for 32 to 45 percent of the Texas high school entering freshmen in any given year between 1996 and 2003. The notable decrease in 2003 in the top 50 Texas feeder high school merits further analyses, but at first glance, may be attributable to overall decreases in the university’s freshmen enrollees resulting from the UT-Austin administrator’s decision to cap or limit undergraduate enrollment. The decrease in the size of the freshmen class, specifically, then decreased the total feeders among the high schools that contributed the most freshmen enrollees in that year, no doubt more so than any direct impact of the Ten Percent Plan.

IDRA’s preliminary review of 2003 feeder high school indicated that (for the most part) the Texas feeder high schools with the largest number of freshmen enrollees tended to have fewer numbers of low-income students (see Attachment A online). This suggests that ability to pay for college has a major impact on who enrolls at the major universities – perhaps neutralizing the potential for enrollment created by the automatic admission provisions in the Ten Percent Plan. This issue of the role of family financial capacity and related financial aid provided to new freshmen enrollees may represent a critical second component of efforts to expand minority enrollment at all Texas major universities.

Finding #4: The Ten Percent Plan increases minority enrollment at UT- Austin.

Recommendation: Before modifying the current Ten Percent Plan, alternative admission procedures must be studied to make sure they yield greater increases in minority enrollments.

What the Data Say: Since the adoption of the Ten Percent Plan, the percentages of minority freshmen enrolling at the state’s major public university has grown over time. At UT-Austin, the percentage of first-time minority freshmen enrollees increased from 33 percent to 45 percent in the same eight-year span.

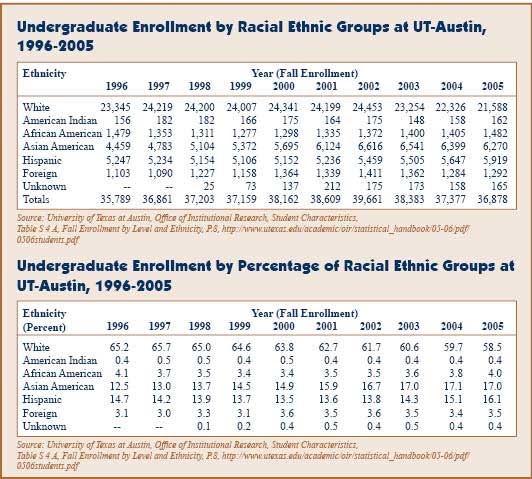

Finding #5: UT-Austin enrolls as many students from other countries as African American students from Texas.

Finding #6: Hispanic undergraduates have only increased an average of fewer than 75 students per year over nine years.

Recommendation: The Ten Percent Plan is a good start but more is needed. Expand recruitment and financial aid for Ten Percent Plan students in order to increase the enrollment of minority students at UT-Austin.

What the Data Say: While the number of minority entering freshmen has improved over time, the university continues to significantly under-serve minority populations in Texas (see Attachment B online). According to data compiled by the UT-Austin Admissions Department, African American students continue to account for less then 4 percent of the university’s undergraduate students with little substantive improvement over time. Hispanic students have reflected increased percentages of the undergraduate enrollment but still lag significantly behind the White undergraduate enrollments at UT-Austin.

Conclusions

Following a closer analysis of student family income and related school’s economic profile data (as reflected in the percent of students eligible for the free and reduced-price lunch program), it is also evident that for students from low-income families, the mere opportunity to enroll at this flagship school is insufficient. If the state’s major places of higher learning are to reflect all of its resident populations, the state must examine the combined effects of percent merit-based admissions, its student recruitment practices, and the level and types of financial aid offered to students.

Though far from perfect, the Ten Percent Plan as currently structured has increased diversity of students who are admitted and enroll at UT-Austin and diversity in the number and distribution of high schools that send their students to the state’s major institution of higher education. Before any significant changes are entertained, any new plan must demonstrate evidence of comparable or better outcomes as it relates to both minority student and high school feeder diversity.

Postscript: Upon the close of the Texas legislative session in late May 2007, while several changes were proposed and debated, no changes to the 10 Percent Plan were ultimately adopted.

Comments and questions may be directed to him via e-mail at feedback@idra.org.

[©2007, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the June- July 2007 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]