by Bricio Vasquez, Ph.D. • IDRA Newsletter • November-December 2019 •

College-level placement in Texas community colleges relies heavily on a single college readiness placement test, the Texas Success Initiative Assessment (TSIA), unless exempt. The state requires most incoming college students to take the TSIA to be assessed in the areas of reading, writing and math. But this practice can lead to higher numbers of students being misplaced into remedial courses.

College-level placement in Texas community colleges relies heavily on a single college readiness placement test, the Texas Success Initiative Assessment (TSIA), unless exempt. The state requires most incoming college students to take the TSIA to be assessed in the areas of reading, writing and math. But this practice can lead to higher numbers of students being misplaced into remedial courses.

For example, one support program coordinator told IDRA: “About 98% [of students] need some form of remediation, usually math… So, here, we call it Grade 13” (Cortez & Cortez, 2012).

In 2017, the Texas Legislature passed House Bill 2223 requiring Texas institutions of higher education to change developmental education to improve student success (THECB, 2018). According to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, 58% of first-year community college students were placed in remedial education in English, reading or mathematics. This number could be minimized if the state did not rely on a single measure for coursework placement. (Weisburst, et al., 2017)

In contrast, alternative holistic assessments of college readiness immediately place students in credit-bearing courses, which leads to higher rates of students transferring to four-year colleges and to higher graduation rates.

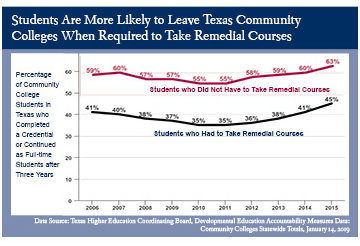

Additionally, Texas’ college readiness and remediation model unintentionally “weeds out” students by locking them into non-credit bearing remedial coursework. The graph below shows the percentage of community college students who completed a credential or continued as full-time students after three years. In the 2015 cohort, for example, only 45.3% of students requiring remedial coursework succeed compared to 63.4% who did not require remediation (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, 2019).

Students placed in remediation courses cannot progress into college-bearing courses until after completing their remediation sequence, even if they only need remediation in a single subject and could be successful in other college-level courses. Remediation courses are not transferable from two-year colleges to four-year universities. This adds time and costs to students’ educational investment.

Despite their intended purpose, remediation courses often hinder students’ progress in college and contribute to student attrition. This system burdens community colleges and the Texas economy. Nationally, remediation courses cost students $7 billion per year, not counting the opportunity cost of time and earning power for students enrolled in these courses or the cost to communities when fewer students make it to graduation (Scott-Clayton, 2012).

Texas higher education needs a more effective approach to college readiness assessment and remediation to ensure more students complete a postsecondary degree.

One example of an alternative college readiness assessment and remediation model is California’s Assembly Bill (AB) 705. This measure reduces, and in many cases, eliminates the number of remedial courses for students needing additional academic support (Rodríguez, et al., 2018).

AB 705 took effect in the fall of 2019 and uses multiple measures for college placement, including high school grade point average (GPA), high school English and math course completion, and high school standardized assessment results. If remediation is required, students enter co-requisite enrollment. The co-requisite model enrolls students simultaneously in credit-bearing, transferable math and/or English courses and a reading and/or math support course. The co-requisite course must be aligned with the learning outcomes of the college-level course. This approach proves more efficient than a sequential course enrollment approach.

Prior to California’s AB 705, community colleges had discretion about how they would approach college placement and remediation. Community colleges that adopted multiple measures similar to those in AB 705 saw dramatic results. For example, San Diego Mesa College saw only 34% of students successfully completing college composition under traditional remediation, whereas 85% accomplished the same via the co-requisite model (Rodríguez, et al., 2018).

California is not the only state using innovative approaches to college placement. The North Carolina Community College System changed its policy on placement after marginal success with its previous model (Clotfelter, et al., 2015; Mazzariello & Ganga, 2019). Other states using multiple measures include Florida, Tennessee and Virginia (Xiaotao Ran, et al., 2019).

Texas college readiness assessments and remediation models that rely on a single test score do more harm than good. They have the unintended effect of denying college access, particularly to first-generation college students and students of color (Bojorquez, 2019).

The Texas approach undermines the efforts of K-12 schools preparing graduates for college-level work (Avilés, 2019). Latinx youth have the highest enrollment rates in Texas community colleges. The current remediation structure hurts Texas’ Latinx student population most.

Alternative approaches, like multiple measures assessment and co-requisite remediation, have higher success rates. In addition, colleges can provide test preparation for high school students taking the TSIA to refresh students’ skills, particularly for those who took Algebra 2 as sophomores or juniors.

Students who do not take Algebra 2 at all will be at a significant disadvantage. In 2013, Texas policymakers removed Algebra 2 as a high school graduation requirement. This change led to a decline in high school students enrolled in Algebra 2, especially in rural schools (Bojorquez, 2018).

Texas needs to monitor its recent changes and take additional steps to produce a skilled workforce that attracts employers and is competitive in this global economy.

Resources

Avilés, N. (2019, May). “Characteristics of College Focused Schools,” IDRA Newsletter.

Bojorquez, H. (2019 rev.). College Bound and Determined. San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association.

Bojorquez, H. (2018). Ready Texas – A Study of the Implementation of HB5 in Texas. San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association.

Clotfelter, C.T., Ladd, H.F., Muschkin, C., & Vigdor, J.L. (2015). “Developmental Education in North Carolina Community Colleges,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis.

Cortez, J.D., & Cortez, A. (2012, May). “Describing the First-Year Experience for First-Time-in-College Students at Major Community College,” IDRA Newsletter.

Mazzariello, A.N., & Ganga, E.C. (2019). Modernizing College Course Placement by Using Multiple Measures. Denver, Colo.: Education Commission of the States.

Rodríguez, O., Mejia, M.C., & Johnson, H. (2018, August). Remedial Education Reforms at California’s Community Colleges: Early Evidence on Placement and Curricular Reforms. San Francisco, Calif.: Public Policy Institute of California.

Scott-Clayton, J., Crosta, P.M., & Belfield, C.R. (2012). Improving the Targeting of Treatment: Evidence from College Remediation. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. (2018). FAQs HB 2223 Implementation. Austin, Texas: THECB.

Weisburst, E., Daugherty, L., Miller, T., Martorell, P., & Cossairt, J. (2017). “Innovative Pathways Through Developmental Education and Postsecondary Success: An Examination of Developmental Math Interventions Across Texas,” Journal of Higher Education.

Xiaotao Ran, F., & Lin, Y. (2019). The Effects of Co-requisite Remediation: Evidence from a Statewide Reform in Tennessee. Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University.

Bricio Vasquez, Ph.D., is IDRA’s education data scientist. Comments and questions may be directed to him via email at bricio.vasquez@idra.org.

[©2019, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the November-December 2019 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]

[©2019, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the November-December 2019 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]