Testimony Presented by David Hinojosa, J.D., National Director of Policy, Intercultural Development Research Association, Before the Texas Senate Higher Education Committee, April 5, 2017

Dear Honorable Chair and Senate Higher Education Committee:

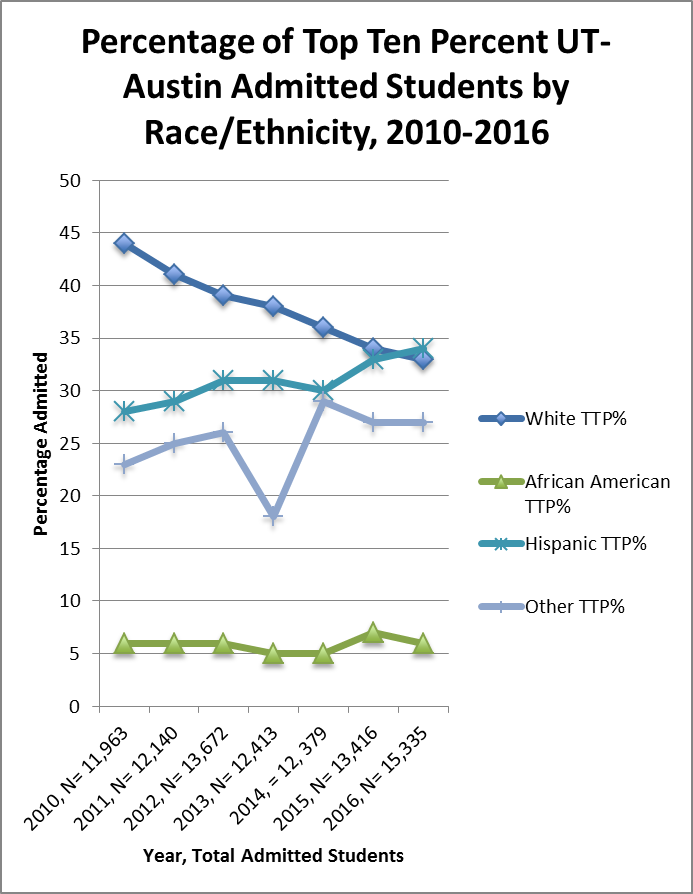

As Texas continues to graduate a more diverse group of students from its public high schools, competition for limited seats at the state’s most popular flagship university, the University of Texas at Austin (UT-Austin), grows tighter and tighter each year. Over the years, the state’s Top Ten Percent Plan has helped ensure a greater racial and geographic diversity of qualified students admitted to and enrolled at UT-Austin.

While the Top Ten Percent Plan is not a stand-alone solution to achieving equal access to the state’s flagship universities, the facts show that the plan has been an effective race-neutral measure at increasing racial, geographic and socioeconomic diversity at UT-Austin.

Rather than further scaling back on the Top Ten Percent Plan, state policymakers should instead explore how other equitable policies can complement the Top Ten Percent Plan and support increased enrollment and completion at our public institutions (see further below for suggestions).

Increased Access for Underrepresented Groups

The Top Ten Percent Plan has opened the doors of the flagship universities to low-income, rural and minority communities – all groups who were typically denied access to the flagships. Facts derived from IDRA’s analyses of the Top Ten Percent Plan since its inception include the following:

- The Top Ten Percent Plan has helped increase the number of feeder high schools into UT-Austin, from 622 in 1996 to 792 in 2000 (Montejano, 2001) to 992 in 2016 (UT-Austin, 2016).

- Rural schools continue to benefit from the plan, with UT-Austin admitting a total of 109 students from 87 rural schools in 2016, up from 85 students and 65 rural schools in 2010 (UT-Austin, 2010 & 2016). The plan accounted for 83 percent of admitted rural students at UT in 2016.

- The Top Ten Percent Plan is the principal admissions driver for African American, Latino and Asian American students into UT-Austin, with 87 percent of admitted Latino students coming from the plan, 77 percent for Black students, 75 percent for Asian American students and 69 percent for White students in 2016.

- In contrast, UT-Austin’s subjective admissions plan disproportionately favors White students. As the charts below show, White students comprise nearly one out of every two Non-Top Ten Percent Plan admitted students (Exhibit 1) but only one out of every three Top Ten Percent Plan students (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 2

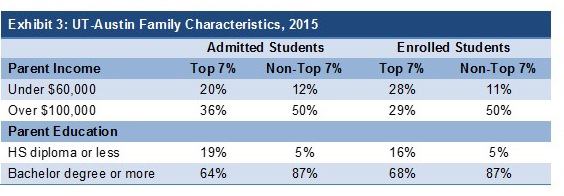

- The Top Ten Percent Plan also yields greater student diversity based on parent income and degree attainment (UT-Austin, 2015).

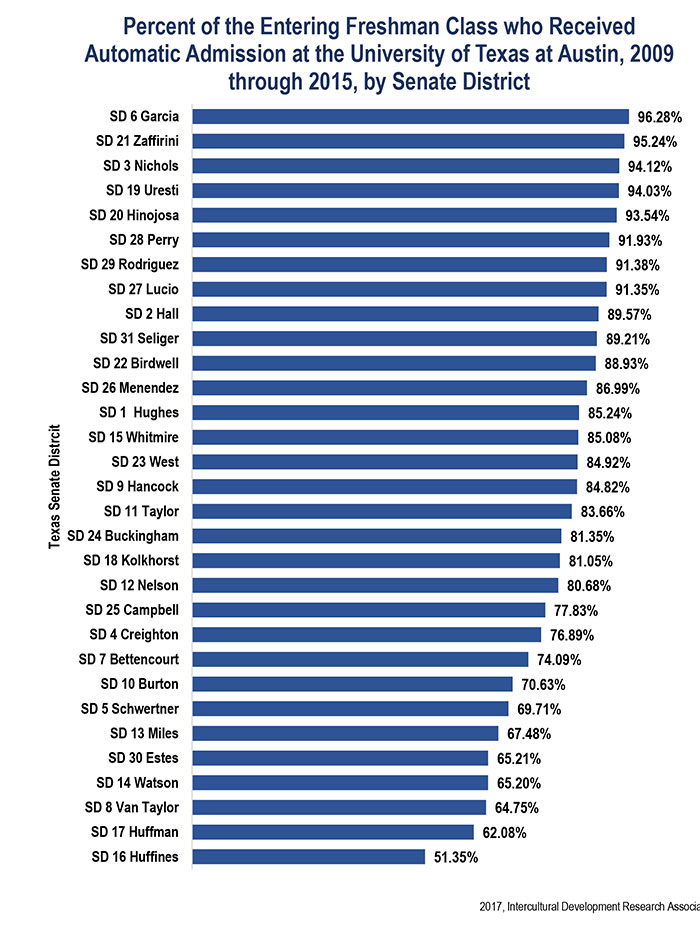

Students in All Senatorial Districts Benefit Greatly from the Top Ten Percent Plan

IDRA analyzed UT-Austin data and the impact of the Top Ten Percent Plan on Texas senatorial districts. As noted below, students in all districts benefit greatly from the plan.

UT-Austin’s Subjective Admissions Plan Tends to Favor Schools in Limited Senatorial Districts

When analyzing the same dataset of enrolled students admitted outside of the Top Ten Percent Plan and under UT-Austin’s subjective admissions plan (non-Top Ten Percent Plan), students in six senatorial districts comprised 57 percent of those admissions (SD 5, SD 7, SD 8, SD 14, SD 16, SD 17). In contrast, those same districts accounted for only 32 percent of Top Ten Percent Plan admissions.

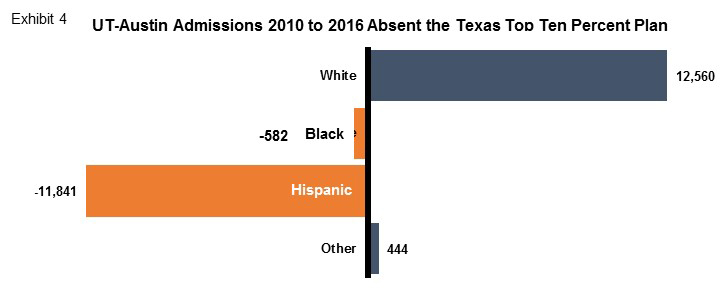

Applying the Rates of Admission under UT’s Subjective Admissions Plan Could Devastate Diversity

As noted above, UT-Austin’s Top Ten Percent Plan admitted students and enrollees reflect a far more diverse group of students than students admitted under the subjective admissions plan. In a hypothetical analysis, IDRA applied the admission rates for Non-Top Ten Percent Plan students (disaggregated by race) for the years 2010 through 2016 to the total number of students admitted, assuming the TTPP was non-existent. The result demonstrated that thousands of mostly Latino students and Black students would have been at-risk of not being admitted, while White students would have been the greatest beneficiaries.

The Top Ten Percent is Constitutional

Some have claimed that the Top Ten Percent Plan was created with the sole purpose of increasing Latino student and African American student enrollment and, therefore, amounts to unlawful discrimination against other students. As I noted in a law journal article published last year, such a simple examination fails to consider the complexities of intentional discrimination (Hinojosa, 2016). First, unquestionably the law on its face is race-neutral. Second, a court would have to stretch the facts and the law very far to find that the actions of the legislature in adopting the Top Ten Percent Plan were intended to harm White students because of their race. In fact, White students continue to benefit from the Top Ten Percent Plan law at rates greater than other student groups when compared to their Texas high school graduating peers (except for Asian American students), which raises the question of whether White students challenging the law would even be able to satisfy the requisite standing principles and to establish a disparate effect.

Further, an examination of the application the Feeney standard and the Arlington Heights factors shows that the Top Ten Percent Plan is not the type of intentional discriminatory law considered to violate the equal protection rights of students under the Fourteenth Amendment (Hinojosa, 2016). Indeed, the legislative history evidences the legislature’s intent of improving access for underserved low-income students, rural students and students of color. In such cases, especially where there is no evidence discriminatory effect, the courts frequently strike down such claims.

Policy Recommendations for Ensuring Access and Opportunity

So where do we go from here? Research shows the overwhelming educational, social and economic benefits that flow from a more diverse university student body and reach all students, such as developing critical thinking and problem solving skills, helping to reduce racial isolation, dispelling racial stereotypes and promoting cross-racial understanding, and building leadership that helps prepare students for life after college.

As a group of Fortune 100 companies explained, student racial diversity is “a business and economic imperative” in the growing, diverse global market (2015). So how can the state reap these benefits and expand diversity and opportunity?

IDRA’s following recommendations represent a blueprint for helping to ensure all qualified students gain access to our public flagships.

Maintain the current blended admissions plan of the subjective admissions plan coupled with the Top Ten Percent Plan capped at 75 percent of admissions at UT-Austin. However, the subjective plan must be examined and revised to ensure qualified African American students and Latino students are not being overlooked for admissions.

Re-regulate tuition at the higher-cost public universities but ensure universities have adequate resources to help make up the difference. Texas lags behind competitor states in the percentage of the state’s gross domestic product spent on public education, including post-secondary education (Harris, 2012). If the state can invest more appropriately, it can begin to reign in high tuition rates.

Provide greater financial aid to students in need. In past sessions, the state has cut already-reduced levels of financial aid based on need. The state must ensure that students not only are admitted, but can afford to enroll and complete college without excessive debt.

Texas must take major steps toward investing in at least five additional major flagship universities. With 80,000 additional students entering Texas PK-12 public schools each year, the state must come to terms with expanding Tier 1 universities.

UT and other public universities must engage in meaningful outreach to underserved communities. As the training ground for future leaders, universities like UT-Austin must collaborate more meaningfully with underserved high schools and underserved students, similar to what has been done with job training, community colleges and public schools.

Texas must re-align its PK-12 curriculum and graduation requirements with college expectations. Unlike its predecessor, the state’s new default PK-12 curriculum adopted under HB 5 in 2013, the “Foundation plus endorsement” program, does not meet many of college entrance requirements and worse, could lead to the channeling of students by race and poverty into less rigorous tracks.

Texas must adequately and equitably support its PK-12 public education system to help prepare students for college and a career. Regardless of the Supreme Court of Texas’ decision on the legal merits of the most recent school finance case, the facts have not changed and the needs of the state’s growing diverse student population have not been met (Texas Taxpayer, 2014 & 2016). Texas must reverse course and support college-readiness in all public schools.

Texas can ill-afford to turn the clock back now as the results would likely be devastating, particularly for minority-majority and rural communities (IDRA, 2009). As IDRA stated in its testimony before the Texas Legislature when the state previously considered reductions to the Top Ten Percent Plan, “It is ironic that at a time when expanding global competition requires better educated citizens, Texas is discussing ways to limit access of its top students to its top institutions of higher learning” (IDRA, 2009).

Texas instead should choose to be a leader as an investor in public education, including higher education, which is not only an investment in that child and the schooling, but an investment in the state’s social, political and economic future.

For more questions, please contact IDRA National Director of Policy, David Hinojosa, J.D., at david.hinojosa@idra.org or 210-444-1710, ext. 1739.

Resources

Abigail Noel Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, et al. (September 2015). Brief of Fortune-100 and other leading American businesses as amici curiae in support of respondents (No. 11-345, affirmative action, consideration of race in University of Texas admissions).

Brief for IDRA as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, Fisher v. UT Austin (2015) (no. 14-981).

Harris, A., & M. Tienda. (April 2012). “Hispanics in Higher Education and the Texas Top Ten Percent Law,” Race and Social Problems, 4(1): 57-67.

Hinojosa, D. (Spring 2016). “Of Course the Texas Top Ten Percent is Constitutional…And It’s Pretty Good Policy Too,” Texas Hispanic Journal of Law & Policy.

Holley, D., & D. Spencer. (1999). “The Texas Ten Percent Plan,” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review (245).

Hopwood v. State of Texas. (2003). 78 F.3d 932 (5th Circuit 1996) abrogated by Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 123 S. Ct. 2325, 156 L. Ed. 2d 304 (2003).

IDRA. (2013). Tracking, Endorsements and Differentiated Diplomas – When ‘Different’ Really is Less (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association).

IDRA. (March 11, 2009a). Research Relating to Measures that Would Limit the Texas Top Ten Percent Plan (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association).

IDRA. (March 11, 2009b). Testimony on HB 52 Relating to the Texas Top Ten Percent Plan (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association).

Montejano, D. (2001). “Access to the University of Texas at Austin and the Ten Percent Plan: A Three Year Assessment.”

Orentlicher, D. (1998). “Affirmative Action and Texas’ Ten Percent Solution: Improving Diversity and Quality,” Notre Dame Law Review (181, 183-85).

Texas Taxpayer & Student Fairness Coalition, et al., v. Williams, No. D-1-GN-11-003130, 2014 WL 4254969 (Tex. App.-Travis Aug. 2014) reversed in part and affirmed in part on appeal, Morath v. Texas Taxpayer & Student Fairness Coalition, No. 14-0776 (Tex. 2016) (“Texas Taxpayer”).

The University of Texas at Austin Reports to the Governor, the Lieutenant Governor, and the Speaker of the House of Representative on the Implementation of SB 175, 81st Legislature, For the periods ending Fall 2009-2016 (various years) (UT).