• By Morgan Craven, J.D. & Kaci Wright • IDRA Newsletter • April 2025 •

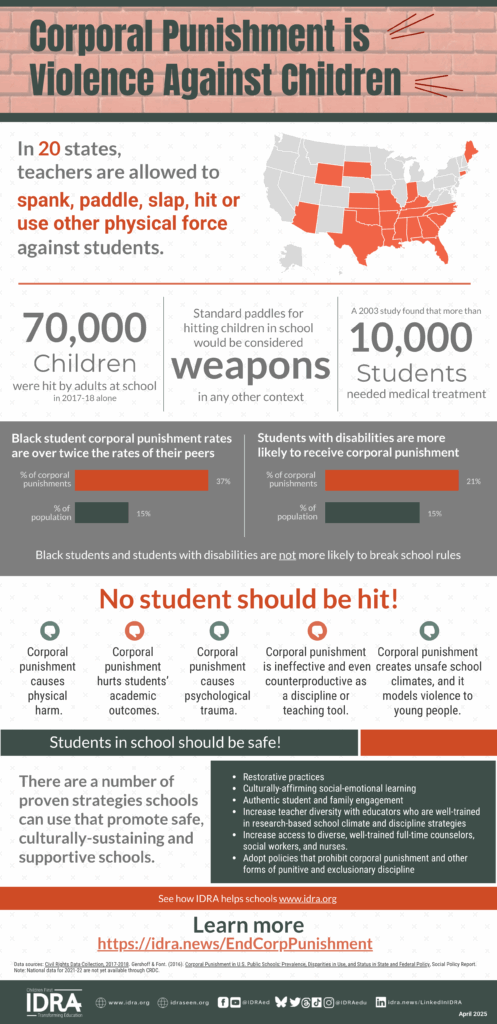

On April 30, we observed International Day to End Corporal Punishment, a global effort to recognize the harms of violence against children and the work we must do to stop it. Though corporal punishment of children has been banned in 68 countries, hitting, paddling, spanking, slapping and other forms of physical punishment remain legal in K-12 schools in 20 U.S. states.

In 2017-18, nearly 70,000 students – some as young as preschool age – were paddled, spanked or hit in their schools (OCR, 2020).

The U.S. Department of Education reported that more than 19,400 students were hit in 2020-21 and 24,500 students in 2021-22. But instances were likely under reported due to COVID-19 school closures. State and national data for 2021-22 are not available through CRDC.

Hitting even one student is harmful. When corporal punishment is used in schools, students are exposed to the well-documented harms of violence, including physical wounds, negative social impacts, and threats to attendance and academic success.

Sadly, this violence against young people is not new. Corporal punishment has a nasty history that is rooted in attempts to control and instill fear in communities of color. The throughlines are clear, and the effects are still felt today.

Fear and control are not conducive to a safe and supportive school environment where all children can learn. In fact, they destabilize school communities and harm students.

Violence Against Black Students

Of the 70,000 students in 2017-18 who received corporal punishment, 37% were Black, though Black students only represent 15% of the student population and are not more likely to break school rules (OCR, 2020).

The majority of states that explicitly allow corporal punishment in schools are located in the U.S. South and Southwest, and the majority of students who received corporal punishment in 2017-18 were in Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi and Texas (OCR, 2020).

From 1882 to 1968, more than 4,000 lynchings occurred in the United States, targeting Black Americans, mainly in those same southern states (EJI, 2017). These public displays of violence, which continued the tradition of physical violence against enslaved and other Black people in the United States, were extra-judicial and designed to terrorize and cause fear, specifically among Black communities.

Researchers have found connections between the prevalence of lynching in communities and other violent acts that occur today, including corporal punishment. The counties in the South that had the highest rates of lynching are significantly more likely to use corporal punishment against students today, particularly against Black students (Ward et al., 2021).

Mississippi had the highest number of lynchings from 1882-1968. Today, it also has the highest rates and the most extreme racial disparities in school corporal punishment (Cunningham et al 2021; Gershoff & Font, 2016).

Nearly 30% of all instances of corporal punishment in U.S. schools in 2017-18 occurred in the state of Mississippi. Black children accounted for 63% of students corporally punished, even though they made up 49% of the student population. Black girls received 73% of the punishments given to girls in the state. (OCR, 2020)

Violence Against Spanish-speaking Students

In 1918, Texas passed laws that forbade the teaching of Spanish in schools. At the time, legislators claimed that speaking Spanish impeded the ability of English learners to learn English and “American” culture (Rodríguez, 2020).

In effect, these “no Spanish” rules banned the use of students’ home language in classrooms and institutionalized decades of abusive and punitive practices, including corporal punishment. According to Mexican American Education Study (MAES) reports, commissioned and published in the 1970s by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Latino students who were caught speaking Spanish were exposed to physical abuse and other punishments, like fines and various forms of humiliation (1972).

The reports revealed: “In many instances, those Chicano pupils who use Spanish, the language of their homes, are punished. The Mexican American child often leaves school confused as to whether he should speak Spanish or whether he should accept his teacher’s admonishment to forget his heritage and identity” (U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1972).

While no school administrators surveyed by the commission admitted using corporal punishment, students shared their experiences in hearings: “Two San Antonio high school students told of being suspended, hit and slapped in the face for speaking Spanish. Another young Mexican American, a junior high school dropout, revealed that one of the reasons he left school in the seventh grade was because he had been repeatedly beaten for speaking Spanish” (U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1972).

The humiliation, physical abuse and trauma that generations of Spanish-speaking st

The humiliation, physical abuse and trauma that generations of Spanish-speaking st

udents experienced are remembered today. Many students who endured shame and abuse in their schools for speaking Spanish later refused to teach their own children Spanish for fear that they too would be targeted in school, creating a cycle of internalized cultural suppression and a loss of early language acquisition (Luna, 2013; Hinojosa et al., 2021).

Currently, it is no longer legal to punish students for speaking Spanish in school. But former students still feel the trauma of physical punishments, and it continues to be forced upon Latino children in schools today.

Latino students in Arizona made up 45% of public students but accounted for 93% of those receiving corporal punishment in 2017-18. Of all Latino students receiving corporal punishment in U.S. schools, 70% were in Texas, where state law still allows children to be slapped, hit, paddled or spanked for discipline purposes (see Spielberger & Fernandez, 2023; TEC, Sec. 37.0011).

Violence Against Native American Students

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, thousands of Native American children were forced to attend federal boarding schools in order to assimilate them into Western culture and strip away their cultural identities (NNABSC, n.d.). By 1925, more than 60,000 children were at these schools where they were forced to use English names, cut their hair and work laborious jobs (Colwell & Montgomery, 2020).

School staff also often inflicted severe corporal punishment against students for “minor offenses,” such as speaking in their Native language. Students who refused to assimilate were beaten, whipped or placed in solitary confinement. (Adams, 2020)

The majority of these boarding schools closed in 1969, but the full truth of how harmful these schools were would be revealed over time. In 2021, the U.S. Department of the Interior launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to investigate the toxic nature of these boarding schools and discovered that nearly 1,000 child deaths occurred at these boarding schools from 1919 to 1969 (Newland, 2022). The physical, mental and emotional abuse students experienced has resulted in intergenerational trauma within Native communities (Brown, 2023).

In 2024, President Joe Biden formally apologized for the U.S. government’s role in the abuse of Native American children that occurred in the boarding schools (Pietrorazio, 2024). Yet, state-sanctioned violence against Native children persists today in public schools.

Native American children receive corporal punishment at almost twice the rate of their enrollment. While comprising 1% of U.S. public school students in 2017-18, they accounted for 1.9% of corporal punishments (OCR, 2020).

Of all Native students who received corporal punishment nationally, 74% were in Oklahoma, the state that also had the highest concentration of federal boarding schools (OCR, 2020; Newland, 2022). Native American students accounted for nearly 25% of Oklahoma students who received corporal punishment, though they only comprised 14% of the student population (see Blatt et al., 2023).

Violence Against Schoolchildren Must End

What do these histories of physical violence against Black, Latino and Native people have in common? They are fundamentally about control, punishment and fear. Threats and acts of violence, by their nature, are designed to force those less powerful to submit to rules and norms out of fear for their safety and well-being. Those purposes remain in schools today.

Students with disabilities are also disproportionately punished. They made up 15% of the U.S. student population in 2017-18 but accounted for 21% of corporal punishments.

Corporal punishment in our schools is fundamentally about controlling students and instilling in them a sense of fear of, rather than connection to, the adults in their school communities. The proof of that persistent and barbaric purpose is highlighted in the words of corporal punishment supporters. In 2023, the Texas House of Representatives debated a bill to ban corporal punishment in schools. One opponent of the ban stood to speak against the bill and reasoned that “kids do need to fear leadership” (2023).

Another opponent of the ban declared that corporal punishment is the

“design God has for disciplining children,” and we must hit students “because we love them because we want to see their future be bright” (Texas House of Representatives, 2023).

In contrast, there is no debate among experts that corporal punishment, fear and control are not conducive to a safe and supportive school environment where all children can learn. In fact, they destabilize school communities and harm students.

IDRA will continue to oppose corporal punishment. We do this work alongside many organizations, schools, school districts and professional associations representing teachers, school administrators, doctors, mental and behavioral health professionals, faith-based communities, legal experts, families and students.

We urge you to join the growing community of advocates dedicated to ending corporal punishment in schools and ensuring that all children have access to excellent and equitable learning environments they deserve.

Resources

Adams, D.W. (2020). Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928. University Press of Kansas.

Blatt, D. McCarty, C., Briggs, L., Hayman, S.L., Fenwick, S., & Flynn, E. (2023). “We Don’t Hit” Ending Corporal Punishment in Oklahoma Schools. Oklahoma Appleseed Center for Law and Justice.

Brown, M. (November 5, 2023). Survivors say trauma from abusive Native American boarding schools stretches across generations. AP News.

Colwell, C., & Montgomery, L.M. (March 5, 2020). Native American Children’s Historic Forced Assimilation. SAPIENS.

EJI. (2017). Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror. Equal Justice Initiative.

Gershoff, E., & Font, S. (2016). Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public Schools: Prevalence, Disparities in Use, and Status in State and Federal Policy. Social Policy Report, 30(1):1-26.

Hinojosa, D., Robledo Montecel, M., & Montemayor, A.M. (2021). “Unmet Promises in Texas Education – Mexican Americans and Persistent Discrimination in Texas Education.” In R. Brischetto (Ed.), Mexican American Civil Rights in Texas: 1968-2018. MSU Press.

Luna, R. (dir). (2013). Stolen Education, documentary. Alemán/Luna Productions.

Newland, B. (May 2022). Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report. U.S. Department of the Interior.

NNABSC. (no date). US Indian Boarding School History. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

OCR. (2020). Civil Rights Data Collection, 2017-2018. U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights.

Pietrorazio, G. (October 26, 2024). Biden apologizes for government’s role in running Native American Boarding Schools. NPR.

Rodríguez, R. (February 15, 2020). Bilingual Education. Texas State Historical Association.

Spielberger, J., & Fernandez, M. (2023). Cruel Schools: The Eighteen States that Still Allow Corporal Punishment in Schools and the Resulting Harms to Children of Color and Students with Disabilities. Lawyers for Good Government.

TEC, Sec. 37.0011. Use Of Corporal Punishment. Texas Education Code.

Texas House of Representatives. (April 26, 2023). 88th Legislative Session Recording.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. (1972). The Excluded Student; Educational Practices Affecting Mexican Americans in the Southwest. Mexican American Education Study.

Ward, G., Petersen, N., Kupchik, A., & Pratt, J. (February 2021). Historic Lynching and Corporal Punishment in Contemporary Southern Schools. Social Problems, 68 (1): 41-62.

Morgan Craven, J.D., is the IDRA national director of policy, advocacy and community engagement. Comments and questions may be directed to her via email at morgan.craven@idra.org. Kaci Wright is an IDRA Education Policy Fellow. Comments and questions may be directed to her via email at kaci.wright@idra.org.

[© 2025, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the April edition of the IDRA Newsletter. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]