Charter School Interim Charge, Testimony of IDRA – Presented by David Hinojosa, J.D., IDRA National Policy Director before the Texas Senate Education Committee, December 7, 2015

Thank you for allowing the Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) the opportunity to provide written testimony of its research and analysis on charter schools in Texas. Our testimony focuses on issues impacting the Texas Senate’s study of the approval, expansion, and revocation of public charter schools in Texas, including the performance of charter schools in Texas and efficiency concerns related to the expanded funding of charter schools. We conclude with a proposal for the Senate to consider an approach to new charters that would aim to ensure high quality, equal educational opportunities in a diverse learning environment.

Founded in 1973, IDRA is an independent, non-profit organization that is dedicated to assuring educational opportunity for every child. Throughout its history, IDRA has been a vocal advocate for the right of every student to equal educational opportunity and has conducted extensive research and analysis on a range of Texas and national educational issues impacting public school children, including charter schools and school finance.

I. Performance of Charter Schools

In 1995, the Texas Legislature authorized the creation of a pilot program of 20 open enrollment charter schools. Charter schools were authorized to offer options for community-based groups that sought to create educational alternatives that might better serve small groups of children living in communities around the state (Robledo Montecel, 2000). The experiment of 20 open enrollment charters has ballooned to more than 200 charters (including charters that have been revoked or rescinded) over the past 20 years – an average of more than 10 new charters per year. The 195 active charters operate 613 schools in Texas. This rapid and continuing increase has occurred despite the State’s ongoing efforts to close charters and despite the inconsistent, volatile performance of charter schools.

A. Accountability Ratings of Charter Operators and Charter School Remain Bleak

The latest Texas Academic Performance Reports released by the Texas Education Agency in November of 2015 show that many charter schools continue to struggle to meet the basic state accountability requirements. The state’s accountability indices are not a high bar, as the district court concluded in the most recent school finance case that a school or district “can have what can only be described as incredibly poor performance results on the STAAR exam and still achieve ‘met standard’ on the accountability system” (Texas Taxpayer and Student Fairness Coalition v. Williams, Findings of Fact 120). Even with these low standards, the state’s investment and experiment with charters looks bleak, at best, when looking at ratings by school district/charter operator:

- One out of every 12 charter operators (8.2 percent) failed to achieve the “met standard” or the lower “alternative standard,” compared to less than one out of every 25 school districts (3.8 percent).

- The true numbers may be even worse, as 10 charters (5.1 percent) were not rated compared to only two school districts (0.2 percent)

| District Ratings By Rating Category

(Excluding Charter Operators) |

||

|

2015 |

||

| Accountability Rating |

Count |

Percent |

| Met Standard/Alternative |

983 |

96.0% |

| Met Standard |

983 |

96.0% |

| Met Alternative Standard |

0 |

0 |

| Improvement Required |

39 |

3.8% |

| Not Rated |

2 |

0.2% |

| Data Integrity Issues |

0 |

0 |

| Totals |

1,024 |

100.0% |

|

TEA. 2015 Accountability System State Summary, November 4, 2015. http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/perfreport/account/2015/statesummary.html |

||

| District Ratings By Rating Category

(Charter Operator Ratings) |

||

|

2015 |

||

| Accountability Rating |

Count |

Percent |

| Met Standard/Alternative |

169 |

86.7% |

| Met Standard |

137 |

70.3% |

| Met Alternative Standard |

32 |

16.4% |

| Improvement Required |

16 |

8.2% |

| Not Rated |

10 |

5.1% |

| Data Integrity Issues |

0 |

0 |

| Totals |

195 |

100.0% |

|

TEA. 2015 Accountability System State Summary, November 4, 2015. http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/perfreport/account/2015/statesummary.html |

||

The ratings by charter campus did not fare much better:

- One out of every nine charter schools (10.8 percent) failed to achieve the “met standard” or the lower “alternative standard,” compared to only fewer than one out of every 14 school districts (6.7 percent).

- Again, the true numbers may be even worse as 75 charter schools (12.2 percent) were not rated for various reasons, twice the rate of traditional public schools (6.1 percent).

| Campus Ratings By Rating Category

(Excluding Charter Campuses) |

||

|

2015 |

||

|

Accountability Rating |

Count |

Percent |

| Met Standard/Alternative |

7,004 |

87.2% |

| Met Standard |

6,836 |

85.1% |

| Met Alternative Standard |

168 |

2.1% |

| Improvement Required |

537 |

6.7% |

| Not Rated |

492 |

6.1% |

| Data Integrity Issues |

0 |

0 |

| Totals |

8,033 |

100.0% |

|

TEA. 2015 Accountability System State Summary, November 4, 2015. http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/perfreport/account/2015/statesummary.html |

||

| Charter Campus Ratings By Rating Category | ||

|

2015 |

||

|

Accountability Rating |

Count |

Percent |

| Met Standard/Alternative |

472 |

77.0% |

| Met Standard |

370 |

60.4% |

| Met Alternative Standard |

102 |

16.6% |

| Improvement Required |

66 |

10.8% |

| Not Rated |

75 |

12.2% |

| Data Integrity Issues |

0 |

0 |

| Totals |

613 |

100.0% |

|

TEA. 2015 Accountability System State Summary, November 4, 2015. http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/perfreport/account/2015/statesummary.html |

||

B. Studies Show Equal or Lower Performance of Students Attending Charter Schools

There have been a handful of studies over the years comparing student performance in charter schools to students in traditional public schools. In spite of the State’s efforts to close many poor-performing or grossly mismanaged charter schools over the years and to scrutinize more closely applications for new charters, students in charter schools often fair no better, and sometimes perform even worse, than their peers attending traditional public schools. A recent study of urban schools by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) – including those in Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, Fort Worth and El Paso – showed mixed results on the performance of students attending charters (CREDO, 2015). Its methodology was critically challenged by researchers from National Education Policy Center, which claims that the CREDO studies suffer because:

- The nature of the comparison between charter and traditional public schools in the CREDO studies is not clear;

- The matching variables used in CREDO’s studies may not be sufficient to support causal conclusions;

- Some lower-performing charter students are systematically excluded from the CREDO studies;

- CREDO’s reasons for the systematic exclusion of lower-scoring charter students do not address the potential for bias arising from the exclusion;

- The “days of learning” metric used in the CREDO studies is problematic;

- The CREDO studies fail to provide sufficient information about the criteria for the selection of urban regions included in the studies;

- The CREDO studies lack an appropriate correction for multiple significance tests; and

- The CREDO studies have trivial effect sizes.

Much of the same methodology was employed in CREDO’s July 2015 study, Charter School Performance in Texas. Even with the serious questions raised regarding CREDO’s methodology, the results are very mixed:

- At-risk students in charter schools make significantly less academic progress in reading and math than at-risk students in traditional public schools.

- In two regions, Dallas and Houston, charter students in Texas outperformed their traditional public school counterparts. Students in El Paso and Fort Worth experienced the greatest lags relative to their traditional public school counterparts.

- Black students in charter schools make less progress in reading and math than Black students in traditional public schools.

- Across all charter schools in Texas, Black students in poverty fall behind 22 days of learning in reading and 29 days in math as compared to impoverished Black students attending traditional public schools.

- Hispanic students in traditional public schools perform significantly better than Hispanic students attending charter schools.

- Hispanic students in poverty who attend charter schools have statistically significantly higher achievement than Hispanic students in poverty who attend traditional public schools in reading (the difference is modest – about seven days of learning). In math, the performance of Hispanic charter students is about equal to that of Hispanic traditional public school students in poverty.

- Overall performance trends are marginally positive, but the gains that Texas charter school students achieve even in the most recent periods studied still lag the progress of their traditional public school peers.

- Despite exemplars of strong results, over 40 percent of Texas charter schools are in urgent need of improvement: They post smaller student academic gains each year and their overall achievement levels are below the average for the state. If their current performance is permitted to continue, the students enrolled in these schools will fall even further behind over time.

- Charter school Boards of Directors also need self-reflection and improvement.

The results reflected above demonstrate that many charter operators and charter schools continue to yield poor student performance results – certainly when compared to the traditional public schools with whom they compete and/or with whom they have replaced. Even for some of the high-performing charter schools, many are accused of inflating results due to “creaming” the better-performing students and pushing out lower performing students (Strauss, 2015). A recent study of New Orleans schools by the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans (ERA) found that school leaders there, including in charter schools, competed for students by “using strategies that range from improving academics to more questionable practices like selecting or excluding students based on ability” (Jabbar, 2015).

II. Is the Addition of Facilities Funding for Charters a Wise and Efficient Investment?

The State must seriously consider whether it should invest even greater public tax dollars in charter schools. Unlike traditional public schools that contribute portions of funding from local maintenance and operations property taxes and local bond elections, the State provides 100 percent of funding under the Foundation School Program (FSP) and Available School Funding (ASF) for charter schools. According to the latest TEA data, charter schools enrolled over 229,140 students (ADA) in 2015-16 (TEA table, 2015). This year, the State is providing over $2 billion in FSP and ASF exclusively for charter schools, which is significantly larger than the revenue per ADA provided to traditional public school districts from the State.

A. District Court Finds that Facility Funding for Traditional Public Schools is Inadequate, Unsuitable and Inefficient and the Legislature Fails to Respond

The State allocates very few dollars to TPS for facilities compared to the growing demands and needs of public schools and the TPS plaintiffs brought suit challenging the lack of facilities funding in Texas Taxpayer and Student Fairness Coalition v. Williams. The district court responded favorably, concluding, “The State’s failure to ensure facilities funding keeps pace with property value growth, inflation, and the growing student population has forced districts to issue more bonds and raise I&S tax rates. In order to finance needed facilities and comply with the state’s 50¢ limit on the issuance of new bonds, districts have been forced to issue debt with longer maturities and greater interest expenses. This increasingly expensive debt, combined with rising I&S tax rates due to lack of state support, has contributed to the loss of meaningful discretion over M&O tax rates” (Williams, at 8). The State failed to respond to the court’s ruling that the state’s funding of facilities was inadequate, unsuitable and inefficient (Texas Taxpayer and Student Fairness Coalition v. Williams, Conclusions of Law 34, 49) during the 84th regular session. The Legislature did not increase the yield for the Existing Debt Allotment, which remains unchanged since it was set in 1999, and provided a mere $55 million under the Instructional Facilities Allotment for FY 2017 (HB 1, 84R).

B. District Court Finds that the Lack of Funding Facilities for Charter Schools is Rational, but Will the Legislature Still Act?

In the same lawsuit, the Texas Charter School Association claimed that the State’s failure to provide its schools facilities funding violated the both the equal protection clause and the efficiency clause of Article I of the Texas Constitution. The district court found that “charter applicants are aware of the funding they will receive from the State when they enter into the charter contract” (FOF 1504). The court also found, “The Legislature, in its discretion, created charter schools to serve as an alternative form of education in Texas, and in doing so, has relaxed applicable personnel requirements, subjects them to different levels of oversight and regulation, and allows them more flexibility in delivering curriculum to their students. These differences serve as a rational basis for the Legislature’s policy choice to fund charter schools differently than it funds school districts” (COL 67). The court denied both claims (COL 90, 92, and 93).

Indeed, the court found that in spite of the lack of specially earmarked funding for facilities:

- The total funding [charter schools] receive under the Foundation School Program per ADA is nearly identical to that available to school districts.

- When considering General Fund revenue per ADA, charter schools fare better than school districts. By Fiscal Year 2012, charter schools received $1,283 per ADA more than school districts. This funding difference exceeds the maximum amount of revenue available to school districts through the EDA program.

- This is similarly true when looking at All Funds revenue.

- Charters accordingly have access to revenue in excess of what is available to school districts, and that revenue is available to meet charter schools’ facility needs (Id. at 16-17.).

(FOF 1505)

III. Is the Expansion of Charter Schools a Wise and Efficient Investment for Texas?

The mixed results noted above on the systemic success of charter schools (or lack thereof) in Texas should give the Legislature great pause in deciding whether to increase charters. Indeed, nothing in the law or the Texas Constitution seems to compel the Legislature to increase the number of charters. In the current school finance case, the charter schools claimed that the charter cap of 215 violated the efficiency clause of Article VII, section 1 of the Texas Constitution. The district court rejected this claim, finding that the cap was rational and that the Legislature was well within its right to restrict the number of charters (COL 69).

The burden to the State of creating additional charters did not go unnoticed. As former Commissioner of Education Robert Scott testified, “When you create a charter, it’s like creating a whole new school district… It adds that level of workload to the agency” (FOF 1473). Indeed, the cap operates as an efficiency gauge, given the volatile performance of Texas charter schools, by:

- Maintaining some control for the Texas Education Agency in overseeing charter schools.

- Reducing the significant burden of limited state staff in reviewing applications for charters, in light of budget cuts to the agency;

- Saving the state tax dollars, due to the state funding of 100 percent of FSP and ASF funding for charter schools, as opposed to public schools that contribute local revenues; and

- Avoiding an even a greater number of lawsuits filed by charter operators seeking to stop the revocation of their charters by the State.

Even Dr. Paul Hill, an expert for the Texans for Real Efficiency and Equity in Education (TREE) intervenors in the current school finance case (who also argued in court that the cap should be eliminated), testified that given the large numbers of low-performing charter schools. Texas may have been too lenient in awarding charters (FOF 1472).

IV. Conclusion and Charter School Proposal

So is the charter “experiment” showing returns worthy of expansion and worthy of shifting limited revenue set aside for public school facilities to charter schools? Given the mixed results of charter schools shown above and the substantial public dollars placed in the hands private charter operators, the evidence suggests that the Legislature should strongly consider directing its attention to how it may improve the educational opportunities for students in its traditional public schools as opposed to increasing the number of charter schools in Texas and using scarce facilities dollars for charter schools.

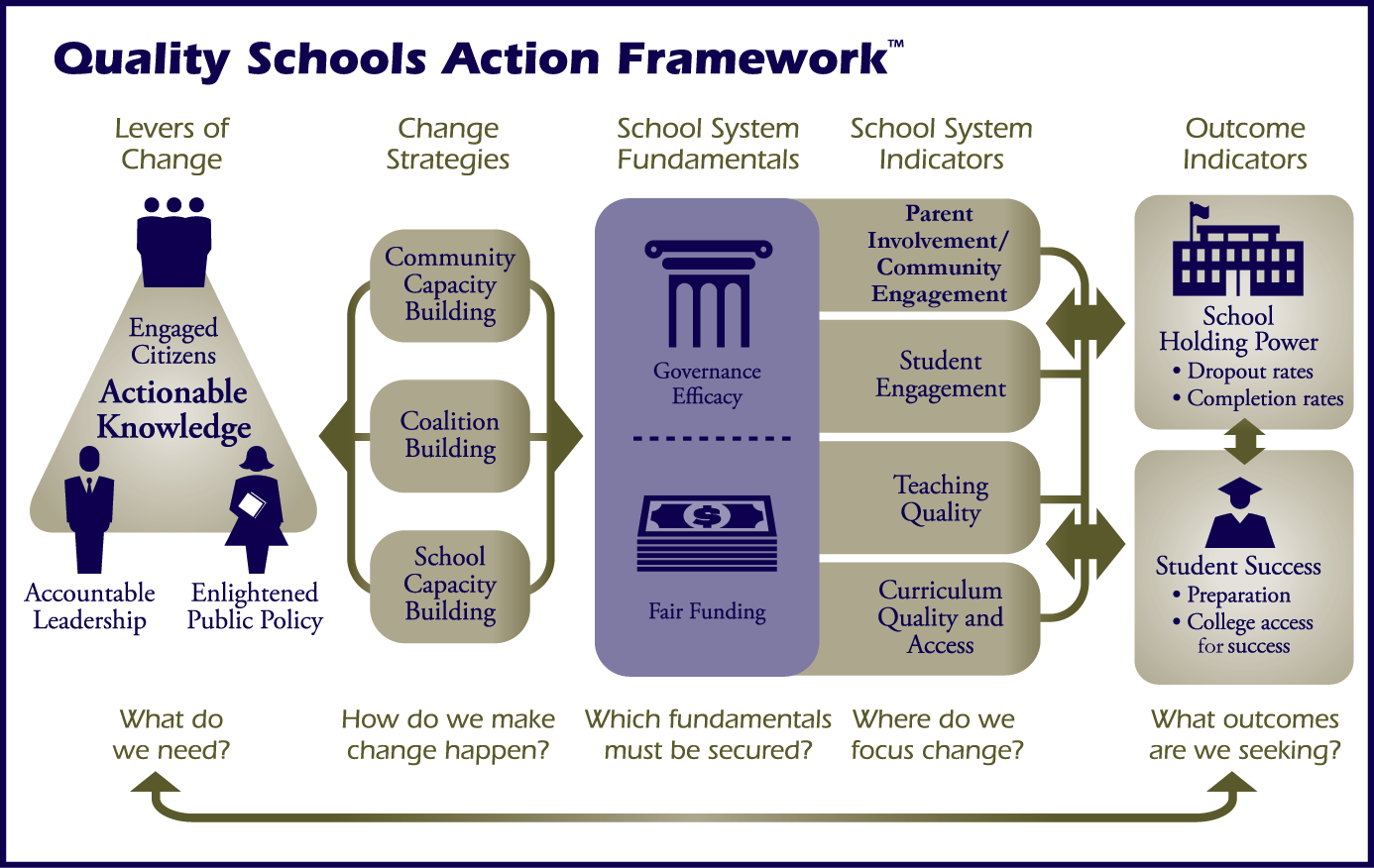

This does not mean that IDRA is advocating for the revocation of all charters. However, rather than looking at efforts to increase the presence of charters – even “successful” charters – the Legislature should look at the whole picture of what it takes to make great schools for all schoolchildren. Continuing to legislate according to the special interests’ latest reform measures has not yielded the results necessary – especially for minority, low-income, at-risk and English learner children. Below is the Quality Schools Action Framework™ developed by IDRA (Robledo Montecel & Goodman, 2010) that may assist the Legislature in drafting future laws that could help the state achieve its public education mission of “ensur[ing] that all Texas children have access to a quality education that enables them to achieve their potential and fully participate now and in the future in the social, economic, and educational opportunities of our state and nation” (Tex. Educ. Code § 4.001).

One example of this approach for the Senate to consider is legislation that would support the creation of diverse school district charter schools, or magnet schools, that integrate students along racial and economic lines in a college-going environment. These schools would capture the original intent of charter schools in 1998, which was to encourage local school districts to experiment with innovative ways of reaching students and to help “reinvigorate the twin promises of American public education: to promote social mobility for working-class children and social cohesion among America’s increasingly diverse populations” (Kahlenberg & Potter, 2014).

Texas could be a national leader in supporting these innovative schools and it could not come at a better time with race relations suffering across the nation and schools experiencing severe racial segregation (Perrone & Bencivengo, 2013). Furthermore, the academic performance of students would not be compromised as integrated schools have been found to benefit both minority and White students academically, socially and emotionally (Seigel-Hawley, 2012). And these schools could be created without running afoul of the Constitution (Ali, R., & Pérez, 2011).

The design of these schools would need to ensure that there are no gatekeeping exams and that each of the elements in the framework shown above are applied. Of course, this also would mean that the Legislature would need to ensure that the proposed schools, as well as all other public schools, are supported with equitable and adequate funding. This type of true public charter school would help silence the critics of certain charter schools that may be reinforcing racial and economic segregation, stripping control from local communities, “creaming” students, and inhibiting transparency of funding and accountability.

IDRA thanks this committee for the opportunity to testify and stands ready as a resource. If you have any questions, please contact IDRA’s National Director of Policy, David Hinojosa, at david.hinojosa@idra.org.

References

Ali, R., & Pérez, T.E. Guidance on the Voluntary Use of Race to Achieve Diversity and Avoid Racial Isolation in Elementary and Secondary Schools (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division and U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, December 2011).

http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/guidance-ese-201111.html

CREDO. Urban Charter School Report on 41 Regions (Stanford, Calif.: Center for Research on Education Outcomes, 2015). https://urbancharters.stanford.edu/download/Urban%20Charter%20School%20Study%20Report%20on%2041%20Regions.pdf

CREDO. Charter School Performance in Texas (Stanford, Calif.: Center for Research on Education Outcomes, July 22, 2015). https://credo.stanford.edu/pdfs/Texas_report_2015.pdf

Jabbar, H. How Do School Leaders Respond to Competition (New Orleans, La.: Education Research Alliance for New Orleans, March 26, 2015). http://educationresearchalliancenola.org/publications/how-do-school-leaders-respond-to-competition

Kahlenberg, R.D., & H. Potter. “The Original Charter School Vision,” New York Times (August 30, 2014). http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/31/opinion/sunday/albert-shanker-the-original-charter-school-visionary.html?_r=0

Maul, A. Problems with CREDO’s Charter School Research: Understanding the Issues (Boulder, Colo.: National Education Policy Center, 2015). http://nepc.colorado.edu/newsletter/2015/09/problems-credos-research

Perrone, C., & B. Bencivengo, “InvestigaTexas report: State leaders, educators and courts grapple with segregated schools,” Dallas Morning News (May 5, 2013).

http://www.dallasnews.com/news/education/headlines/20130504-texas-leaders-educators-and-courts-grapple-with-segregated-schools.ece

Robledo Montecel, M. Testimony on Texas Open Enrollment Charter Schools, Senate Education Committee (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, August 2000). http://www.idra.org/resource-center/texas-open-enrollment/

Robledo Montecel, M., & C. Goodman. Courage to Connect: A Quality Schools Action Framework™ (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, 2010). http://www.idra.org/change-model/college-bound-determined/

Siegel-Hawley, G. How Non-Minority Students Also Benefit from Racially Diverse Schools, Research Brief (Washington, D.C.: National Coalition on School Diversity, October 2012).

http://www.school-diversity.org/pdf/DiversityResearchBriefNo8.pdf

Strauss, V. “Separating Fact from Fiction in 21 Claims About Charter Schools,” Washington Post (February 28, 2015). https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2015/02/28/separating-fact-from-fiction-in-21-claims-about-charter-schools/

Texas Education Agency. 2015 Accountability System State Summary (Austin, Texas: November 4, 2015). http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/perfreport/account/2015/statesummary.html

Texas Education Agency. Charter School Summary of Finances – 2015-2016 Statewide Summary of Finances online table, Last Update: Nov 10, 2015 (Austin, Texas: Texas Education Agency. 2015). https://wfspcprdap1b16.tea.state.tx.us/Fsp/Reports/AsyncCrystalReportViewer.aspx?rpt=33&year=2016&run=15961&charters=N&format=html

Texas Taxpayer and Student Fairness Coalition v. Williams. District Court Final Judgment (D. Tex. 2014) No. D-1-GN-11-003130, 2014 WL 4254969. http://static.texastribune.org/media/documents/DietzFinalJudgment.pdf

Texas Taxpayer and Student Fairness Coalition v. Williams. Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (D. Tex. 2014) No. D-1-GN-11-003130, 2014 WL 4254969.

http://static.texastribune.org/media/documents/DietzSchoolFinanceFindingsofFact.pdf

IDRA is an independent, private non-profit organization, led by María Robledo Montecel, Ph.D., dedicated to assuring educational opportunity for every child. At IDRA, we develop innovative research- and experience-based solutions and policies to assure that (1) all students have access to and succeed in high quality schools, (2) families and communities have a voice in transforming the educational institutions that serve their children, and (3) educators have access to integrated professional development that helps to solve problems, create solutions, and use best practices to educate all students to high standards.