• by Paula N. Johnson, Ph.D., & José A. Velázquez, M.Ed. • IDRA Newsletter • March 2019 •

Schools across the country are focused on resolving behavior issues in ways that minimize students’ out-of-class time. The use of exclusionary practices has declined over the past several years (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, 2018). An increasing number of schools are adopting a “whole child” approach to student learning and success built on relationships and community (Grayson, 2016). In this article, we explore equitable approaches for addressing student behavior.

Schools across the country are focused on resolving behavior issues in ways that minimize students’ out-of-class time. The use of exclusionary practices has declined over the past several years (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, 2018). An increasing number of schools are adopting a “whole child” approach to student learning and success built on relationships and community (Grayson, 2016). In this article, we explore equitable approaches for addressing student behavior.

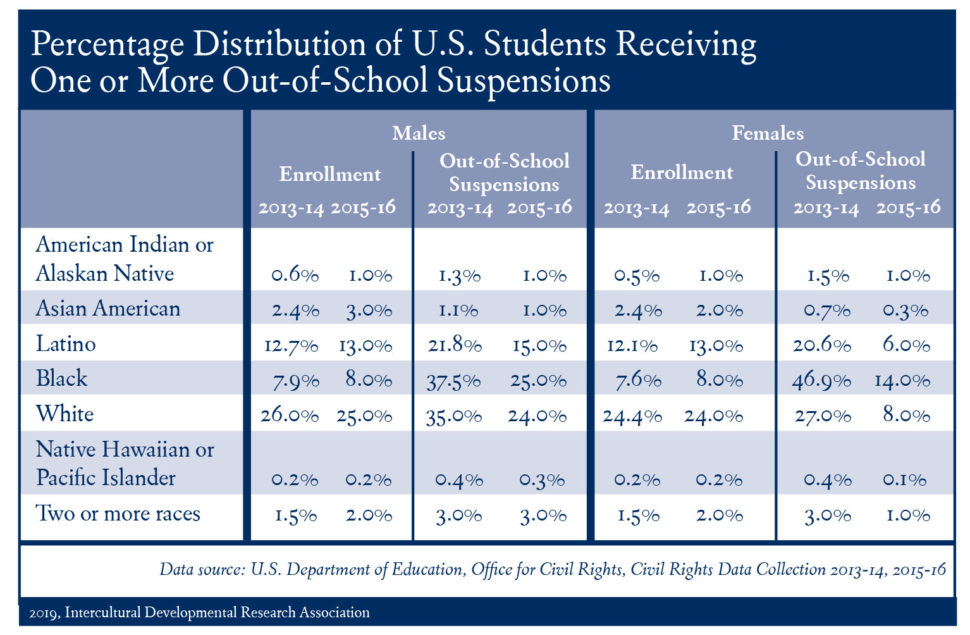

The most recent Civil Rights Data Collection reports (2016; 2018) show a decline in suspension rates for both males and females. There also have been significant decreases in out-of-school suspensions for Black, Hispanic and White students. However, racial disparities in suspensions are still apparent in K-12 schools. Out-of-school time due to suspension is one of the leading variables impacting poor academic performance and attrition in school.

Disproportionate representation in out-of-school suspensions is most notable for Black students. Though Black males and White males account for 24 percent to 25 percent of male out-of-school suspensions, Black males represent only 8 percent of all male students enrolled compared to 25 percent for White males. This means that Black males experience exclusionary disciplinary practices at more than three times their rate of enrollment. Similarly, Black female students are experiencing out-of-school suspensions at almost twice the rate of their enrollment.

Building School Capacity

The IDRA EAC-South has a three-pronged approach to addressing disparities in school discipline. Our technical assistance builds capacity to increase positive school climates through a series of research-based services, including cultural competency and implicit bias training related to school discipline practices for administrators, faculty and staff. Second, we work with schools to revise discriminatory student discipline practices to better align with the district’s tiers of support for behavior. And third, we build capacity for effective family and parent engagement based on IDRA’s family leadership model.

As a result, districts across the region report lower rates of suspension and expulsion each year. Additionally, administrators, teachers and staff are implementing strategies designed to de-escalate conflict and foster more positive learning environments. Parents report an increase in self-regulation and less out-of-class time for their children.

In one example, technical assistance provided to one partner district in our region aided in implementing a comprehensive plan to address disproportional discipline practices, attrition and graduation rates. Racial disparities between Black and White student achievement had troubled the district for many years. With just under 8,000 students, enrollment is almost equally divided between the two student groups. Administrators were pleased with the district’s progress and grateful for the four-year partnership with IDRA, including IDRA’s data tools and training.

Efforts by many school and community leaders to reverse the disparity trends are paying off nationally as well. The rate of out-of-school suspensions fell from 38 percent to 25 percent for Black males from 2013-14 to 2015-16. Likewise, there was a surprisingly steep decline in the percentage of Black females receiving out-of-school suspensions over the same two-year period to 14 percent in comparison to the staggering 47 percent two years prior. The rates for Hispanic and White students also saw declines (see table on Page 4).

Social Emotional Learning

The human connection within a community of learners is key to creating safe learning spaces. A positive school culture hinges upon meaningful relationships grounded on trust, mutual respect and deep regard for human dignity. Social emotional learning (SEL) plays a key role in this process. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL, 2019) describes SEL as “the process through which children and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.” It is a process by which educators and students build capacity and sustainability as they learn and grow together.

A few potential SEL opportunities that contribute to the overall school culture include the manner by which students and parents are greeted as they walk into the campus, the words and tone used by the principal as she provides individual feedback to teachers after observations, and the classroom interactions created by collaborative learning activities.

A growing body of scientific evidence links SEL to improved academic performance (Aspen Institute National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development, 2018). Giving students the opportunity to practice social and emotional skills while learning academic content fosters a sense of self-efficacy while boosting self-confidence and a sense of belonging. Such experiences help children counter the detrimental pressures felt by testing, social inequities and economic disparities, among others.

Teacher Professional Development Related to Student Trauma

While developing a positive and equitable learning environment for all children, educators can build on their skills to appropriately respond to the effects of trauma on youth. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2017) found that more than two-thirds of children suffered at least one traumatic incident by age 16.

Listen to IDRA’s Classnotes Podcast episode: District Innovation Reverses Truancy

As school counselors take on more administrative roles related to testing, scheduling and academic guidance, teachers struggle to create trauma-informed learning environments that are safe havens for students who have had adverse childhood experiences. Without professional development and support, “teachers who are unaware of the dynamics of complex trauma can easily mistake its manifestations as willful disobedience, defiance or inattention, leading them to respond to it as though it were mere ‘misbehavior’” (Terrasi & Crain de la Galarce, 2017).

Systemic, ongoing professional development must engage district and campus leadership to ensure fidelity of implementation. This requires preparing teachers with trauma-informed practices and structures that provide effective and efficient support systems.

The dynamics of meaningful human relationships are at the heart of effective response support to students impacted by trauma. Restorative dialogues that include fellow classmates, classroom teachers and significant adults during “circle” processes have the potential to transform the way educators and students perceive each other in positive ways. (For more information about restorative practices, see article on Page 6.)

Removing a student from the education environment or, in some cases, from the school entirely, impedes their opportunity to learn. For all students to be academically successful, we must develop a system of supports to increase positive behaviors that increase time for teaching and learning.

Resources

CASEL. (2019). What is SEL? webpage. Chicago: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning.

Grayson, K. (August 2016). “Positive School Climates and Diverse Populations,” IDRA Newsletter.

Office for Civil Rights. (2016). 2013-14 Civil Rights Data Collection: A First Look. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education.

Office for Civil Rights. (2018). 2015-16 Civil Rights Data Collection: School Climate and School Safety. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education.

SAMHSA. (2017). Understanding Child Trauma, webpage. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Teaching Tolerance. (2015). Code of Conduct: A Guide to Responsive Discipline. Montgomery, Alabama: Teaching Tolerance.

Terrasi, S., & Crain de la Galarce, P. (July 2017). “Trauma and Learning in America’s Classrooms,” Phi Delta Kappan.

Paula N. Johnson, Ph.D., is an IDRA education associate and director of the IDRA EAC-South. Comments and questions may be directed to her via email at paula.johnson@idra.org. José A. Velázquez, M.Ed., is an IDRA education associate. Comments and questions may be directed to him via email at jose.velazquez@idra.org.

[©2019, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the March 2019 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]