• by David G. Hinojosa, J.D. • IDRA Newsletter • September 2017 •

For several decades, debates have dominated statehouses across the country on whether money makes a difference in education. This debate often surfaces whenever a question arises about whether the state is fulfilling its obligation to equitably and sufficiently fund a quality education of all students in all school districts.

For several decades, debates have dominated statehouses across the country on whether money makes a difference in education. This debate often surfaces whenever a question arises about whether the state is fulfilling its obligation to equitably and sufficiently fund a quality education of all students in all school districts.

Yet, despite rhetoric from a few holdouts surmising that money does not make a difference in education, most readily acknowledge that money can make a difference (Hanushek, 2015). Indeed, strong, recent research shows that increased funding by the states has contributed to both improved student performance and lifetime outcomes, especially for underserved students (Jackson, 2016; Lafortune, 2016).

Figuring out the true costs of educating all students is not an exact science. However, there is a cost for virtually every education service and for ensuring a well-educated workforce to serve students. Education cost studies – when done right – can provide policymakers estimates of funding actual student need. This is a first critical step in enabling policymakers to bridge educational funding policy with effective research and practice.

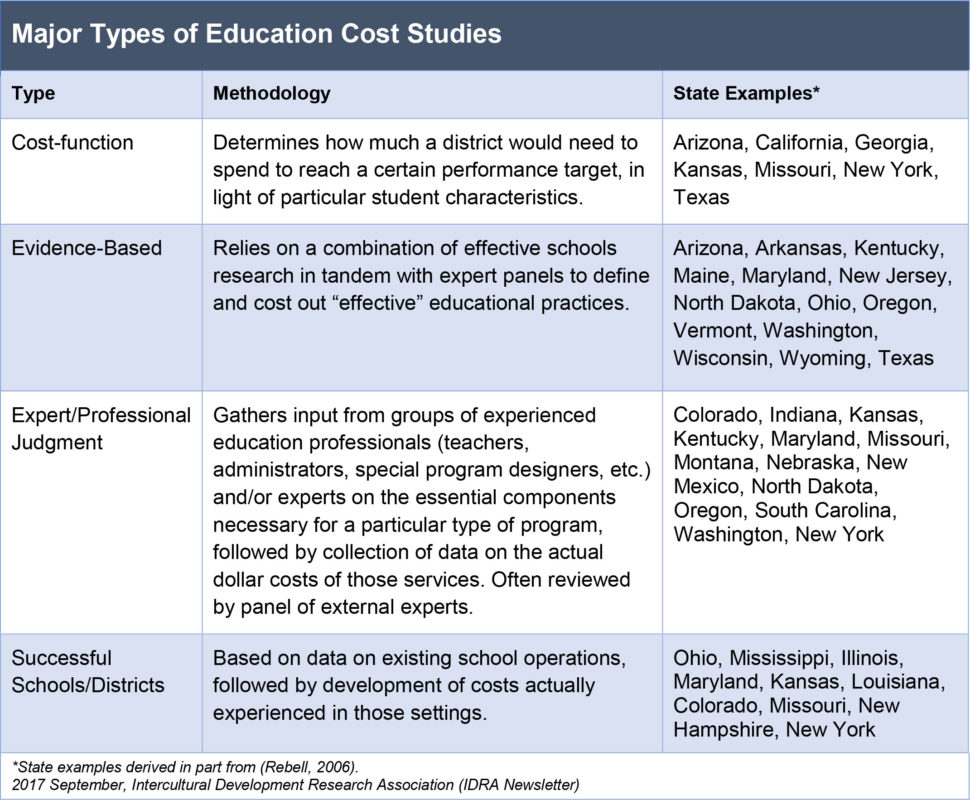

Education cost studies take several forms. They range in rigor and quality with each having its strengths and weakness. Some are more quantitative focused, such as cost function analyses, and others are more qualitative focused, such as professional judgment panels. More than 50 cost studies have been conducted across the states. The table below identifies the four most frequent types of cost studies.

Potential Shortcomings in Cost Studies for Underserved Students

For decades, experts have conducted valid cost studies that serve as potential resources for policymakers. In 1976, IDRA engaged in a Texas-based cost study using an expert panel methodology to identify critical elements of an effective bilingual education program. These included costs unique to the implementation of the specialized program: student assessment, program evaluation, supplemental materials, staffing, staff development and parent involvement (Robledo, 2008). The cost levels varied slightly depending on the grade levels involved and the number of years a program had been in existence, with newer programs reflecting slightly higher costs for start-up. The results led to a recommended funding weight between 0.25 and 0.42, meaning districts would receive between 25 percent and 42 percent more funds above the basic allotment (Robledo Montecel & Cortez, 2008). Later replications of the 1976 IDRA study included analyses of costs in Colorado and Utah, which determined that costs include additional resources needed to recruit and retain bilingual teachers (Robledo Montecel & Cortez, 2008).

Around the same time, the Texas Governor’s Office of Educational Research and Planning conducted an audit of exemplary school districts, resulting in a recommendation for a “beginning” bilingual weight of 0.15 for bilingual education programs, with an increase to 0.40 in two years. The governor’s proposal was defeated, and the allotment was instead set at a substantially reduced rate (Dietz, 2004). Texas has followed these failed policies for decades, ignoring other cost studies. The underperformance of English learner (EL) and low-income students reflects these policies (IDRA, 2017).

Cost studies can, however, fail to adequately consider the needs of underserved students, including English learner and low-income students. These deficiencies may result from either a lack of expertise of empaneled experts or a deficit-oriented perspective of the capabilities of underserved students.

For example, a professional judgment panel may not have strong experts in EL programs who are familiar with critical, research-based services. In an evidence-based study, experts may not distinguish between language needs for EL students and their content needs associated with their poverty.

In a cost-function analysis, experts may lower the expected pass rates for certain underserved groups due to past performance under an inadequately funded school system, rather than costing out their potential success in an adequately funded system. In a successful school study, experts may highlight lower spending schools that enroll fewer underserved students, thus failing to capture the costs associated with successful programs for underserved students.

Linking Research-Based Practices to Cost with School Finance Policy

While money alone will not ensure a high-quality education for underserved students, money well spent on research-based practices and monitored effectively can lead to more effective educational opportunities and success.

For example, research shows that reduced class sizes can have an appreciable impact on achievement and lifetime outcomes for students of color and low-income students (Krueger, 2003). If a school district with high concentrations of low-income students has a well-financed budget, it can hire more teachers and reduce class sizes.

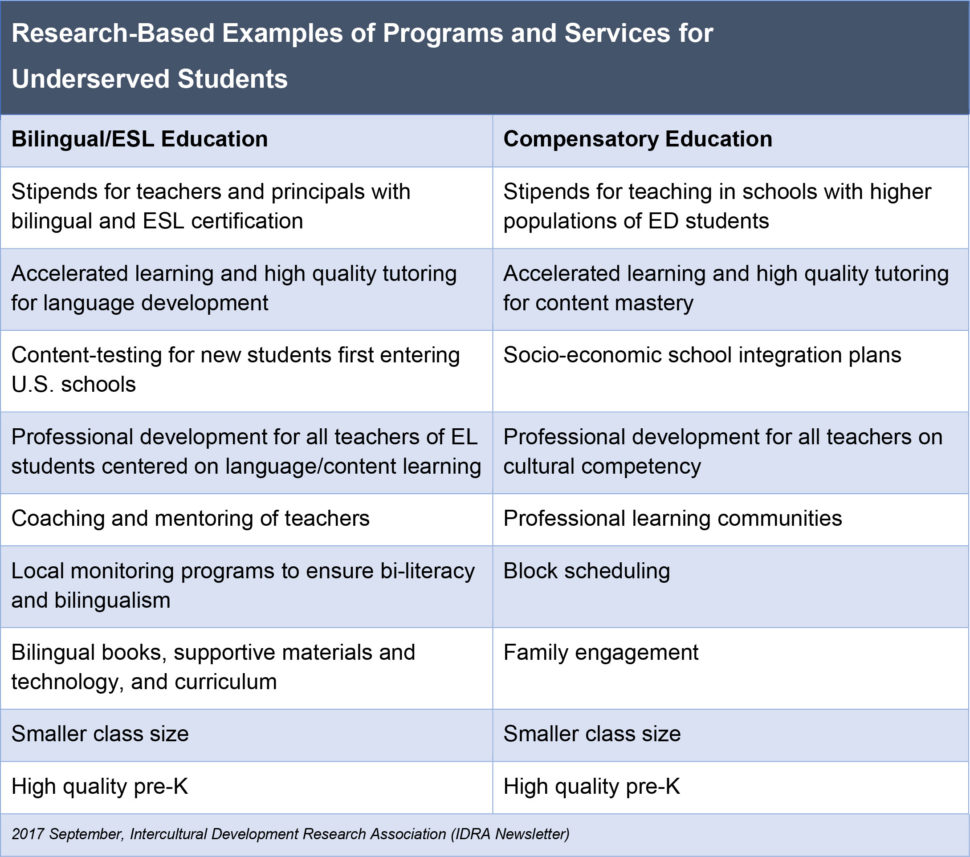

Similarly, fair funding can help a school district recruit, hire and retain high-quality teachers, especially for high-minority schools; offer full-day pre-kindergarten programs; sustain teacher mentoring programs; and ensure other research-based opportunities that lead to student success – especially for underserved communities. The table below is a non-exclusive listing of services that can support improved learning opportunities for underserved students.

Conclusion

While policymakers cannot guarantee results in education performance, they can help ensure educational opportunities for all students with effective school finance policies. To get there, statehouses must tie educational needs and research-based opportunities with the actual costs.

In addition to costs identified above for underserved students, other actual costs must be considered for regular programs and services, such as the costs of sustaining a high-quality teaching and school leader force, transportation, facilities, technology and curriculum, custodial services, professional development, innovation and enrichment, and small district adjustments, among others. Once policymakers understand the actual costs of providing essential educational opportunities, they can get to work on equitably funding those opportunities for all children in all schools.

Resources

Cortez, A. (2012). Report of the Intercultural Development Research Association Related to the Extent of Equity in the Texas School Finance System and Its Impact on Selected Student Related Issues, Prepared for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund in Texas Taxpayer & Student Fairness Coalition v. Williams, No. D-1-GN-11-003130, Travis Co. District Court (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association).

Dietz, J.K. (2004). West Orange-Cove Consolidated Independent School District v. Neeley, Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, 2004 WL 5719215 (Travis County District Court).

Hanushek, E. (July 7, 2015). “Does Money Matter after All?,” Jay P. Greene’s Blog.

Jackson, C.K., & R. Johnson, C. Persico. (2016). “The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Academic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 157-218 (Oxford University Press).

Krueger, A. (2003). “Economic Considerations and Class Size,” Economic Journal, 113 (February), F34-F63.

Lafortune, J., & J. Rothstein, D. Whitmore Schanzenbach. (2016). School Finance Reform and the Distribution of Student Achievement, NBER Working Paper No. 22011 (National Bureau of Economic Research).

Rebell, M. (2005). A Costing Out Primer (New York, NY: Campaign for Fiscal Equity, Inc.).

Robledo Montecel, M., & Cortez, A. (2008). “Costs of Bilingual Education,” Encyclopedia on Bilingual Education (Vol. 1, pp. 180-183). Sage Publications.

David Hinojosa, J.D., is IDRA’s National Director of Policy and Director of the IDRA EAC-South. Comments and questions may be directed to him via email at david.hinojosa@idra.org.

[©2017, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the September 2017 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]