• By Morgan Craven, J.D. • IDRA Newsletter • March 2024 •

We know from a growing body of research that strong relationships; diverse, well-trained teachers and staff (including mental and behavioral health professionals); proactive and meaningful problem solving; and swift, appropriate reactions to the needs of the school community are the keys to creating safe and welcoming schools (Craven, 2022). Punitive, exclusionary discipline and school-based policing are not (Tocci, et al., 2023).

Still, some policymakers continue to draw incorrect and unsupported connections between school safety and harmful forms of discipline and criminalization (Wall, 2023). They wrongly believe that punishing and policing small behaviors – even ones that are age appropriate or a symptom of an underlying need – will create safer schools and prevent future violence.

Worse, they pass policies that rely on these beliefs, providing a false sense of security to some, while ultimately setting up expensive, ineffective interventions that may actually cause harm to students and school climates. (See Rebekah Skelton’s article on Page 5 for an analysis of how these beliefs have shaped federal and state laws and policies over the last three decades.)

Rather than pouring money into costly, ineffective and harmful discipline and policing practices, policymakers at all levels and school leaders must invest in research-based practices that encourage relationship building and problem solving.

How does the harmful school safety-discipline cycle work?

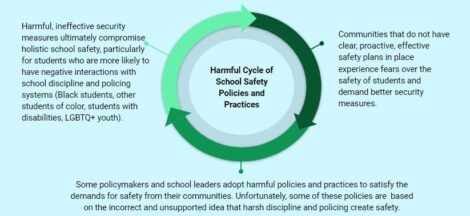

We are seeing a repeated cycle of harmful school security policies and practices that are not providing real safety and are actually compromising the welcoming schools we want for all students. How does this happen?

First, many states, school districts and campuses do not have a clear and well-communicated system of holistic, preventative and proactive school safety. When these systems are not in place and are not clearly articulated to the school community, then teachers, students and families may have understandable concerns over campus safety, especially following horrific violence in other schools. These concerns can result in demands for change and stronger, more visible security measures.

In response to these fears, some policymakers and school leaders adopt policies and practices that criminalize, punish, and isolate students and lead to fractured relationships. Some may invest in harmful, costly and ineffective – yet highly visible – approaches, like school-based police and extreme surveillance and school hardening measures.

These leaders may take a zero-tolerance approach to student behaviors, incorrectly promoting the idea that punishing and criminalizing small behaviors will somehow prevent larger problems.

These harmful policies and practices focus on being reactive – not preventative or proactive. They incorrectly assert that extreme discipline and policing increase safety. These policies are particularly detrimental to the well-being of the students who are most likely to be unfairly targeted by punitive school discipline and policing practices: Black students, students with disabilities and LGBTQ+ students (CRDC, 2021).

Finally, these harmful discipline policies and practices can result in diminished access to information and poor relationships between students and adults in schools. Critically, they isolate students and families who may need support and could benefit from the detection, protection, and referral services schools can provide, including services to address mental health needs or bullying and harassment.

In other words, when schools push children out, rather than pull them in when children need support, they miss opportunities to help address students’ needs.

The vast majority of young people experiencing challenges in their personal lives or at school will never commit violent acts. For the very few who have, four out of five times another person has had knowledge of their plans to act (Vossekuil, et al. 2004).

Discipline systems that rely on isolation and criminalization create environments where students are discouraged from leaking important information. They may not confide in an adult about a challenging situation because they are afraid of getting themselves or another student into trouble.

Weakened relationships and fearful students leave campuses unsafe and block schools and other protective systems from identifying and proactively addressing problems.

Rather than pouring money into costly, ineffective and harmful discipline and policing practices, policymakers at all levels and school leaders must invest in research-based practices that encourage relationship building and problem solving.

These practices may include frameworks like multi-tiered systems of support or restorative practices but should be responsive to the needs and resources of the school community (Tocci, 2023; Duggins-Clay, 2022).

Policymakers and school leaders should also ensure all schools have diverse and well-trained teachers, nurses and mental and behavioral health professionals that have the support and time to address the needs of students and adults in the school. Investing in these and other proven strategies will help to promote safe schools without excluding or criminalizing students.

Learn More

See IDRA’s Bilingual Infographic: Build Safe Schools, Reject Hurtful Policies

See IDRA’s Issue Brief: What Safe Schools Should Look Like for Every Student – A Guide to Building Safe and Welcoming Schools and Rejecting Policies that Hurt Students, by Morgan Craven, J.D.

Resources

CDRC. (2021). 2017-18 State and National Estimations. U.S. Department of Education, Civil Rights Data Collection.

Craven, M. (June 2022). What Safe Schools Should Look Like for Every Student A Guide to Building Safe and Welcoming Schools and Rejecting Policies that Hurt Students. IDRA.

Duggins-Clay, P. (June-July 2022). Implementing Restorative Practices to Strengthen School Communities. IDRA Newsletter.

Tocci, C., Stacy, S.T., Siegal, R., Renick, J., LoCurto, J., Lakind, D., Gruber, J., & Fisher, B.W. (October 2023). Statement on the Effects of Law Enforcement in Schools. Society for Community Research and Action.

Vossekuil, B., Fein, R.A., Reddy, M., Borum, R., & Modzeleski, W. (June 2004). The Final Report and Findings of the Safe School Initiative: Implications for the prevention of School Attacks in the United States. U.S. Secret Service and U.S. Department of Education.

Wall, P. (March 2023). Lawmakers Across U.S. Push for Harsher School Discipline as Safety Fears Rise. Chalkbeat.

Morgan Craven, J.D., is the IDRA national director of policy, advocacy and community engagement. Comments and questions may be directed to her via email at morgan.craven@idra.org.

[© 2024, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the March edition of the IDRA Newsletter. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]