Create Safe and Welcoming Pathways for All Students

Students need safe and welcoming school environments to learn. Disciplinary practices that push students out of classrooms, physically punish them, or put them into contact with police officers are ineffective and harmful. These punitive strategies cause students to miss important learning and social time with their teachers and peers; can lead to trauma and disengagement from school; and increase the likelihood of grade retention, students dropping out, and contact with the justice system.

This process of exclusion, punishment and poor outcomes is known as the school-to-prison or school-to-deportation pipeline. Rather than simply punishing students, schools should focus on creating safe and welcoming campus climates that put students on the pathway to college and life success.

How the Texas School-to-Prison and Deportation Pipeline Harms Students

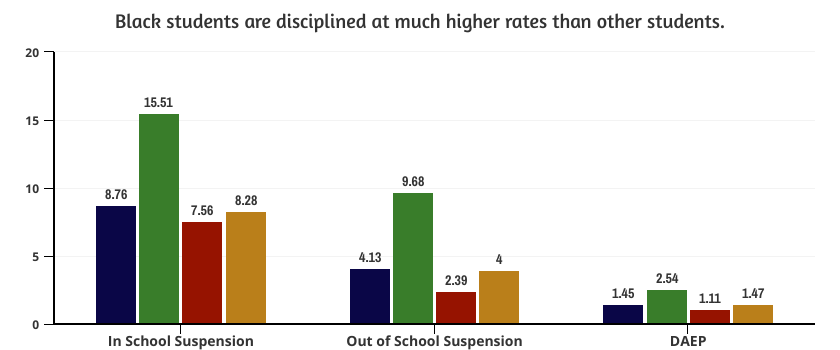

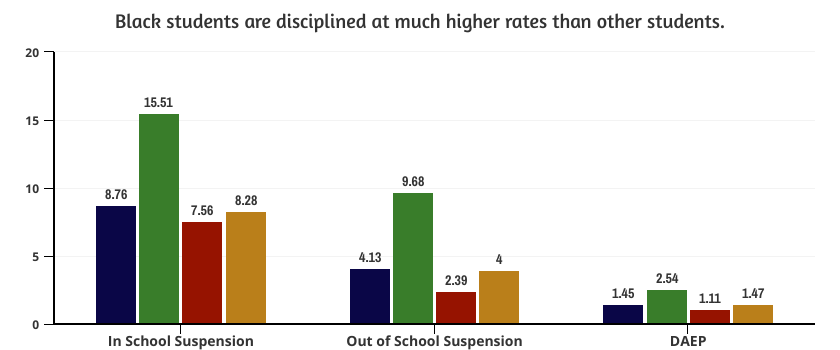

Black students, Latino students and LGBTQ students experience greater rates of school discipline and have higher contact with police in their schools than their peers, even though they are not more likely to misbehave (GLSEN, 2016; U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 2019). Students with disabilities also are disproportionately punished and referred to police, even though their behaviors may stem from their disability and require non-punitive interventions and supports.

In Texas, students can be suspended in school or out of school, sent to alternative schools called disciplinary alternative educational program (DAEPs) and expelled to the street or to juvenile justice alternative educational programs (JJAEPs).

Additionally, Texas still permits schools to practice corporal punishment with students. This means that school administrators may intentionally hit, spank and slap students as a form of discipline. These harsh security and punishment measures often harm students of color and students with disabilities (Gershoff & Font, 2016; Startz, 2016).

Schools also use police officers and courts to control and punish students. Though there is no evidence they increase school safety, police officers are able to patrol campuses, arrest students, collaborate with federal immigration authorities and use force. Many “school safety” measures – including increasing the regular presence of police inside schools, arming teachers, and adopting unnecessary surveillance and barriers in the school building – are not based in research. They can actually end up harming students and school climates (Wilson, 2020, additional cite to our policing letter?).

Harmful, overly-punitive punishments send students out of their classrooms, creating barriers to their academic and social success. These discriminatory punishments make schools less safe and often have more to do with the perceptions of teachers and administrators than the actual behaviors of the students. School policies and practices should be fair and appropriate and should focus on building strong and trusting relationships between students and adults.

Recently, in Texas and across the country, communities have adopted “school safety” measures in response to high-profile, violent tragedies in schools.

Policy Recommendations for Texas

The Texas Legislature should…

- End abusive punishment techniques in schools, like corporal punishment.

- Eliminate invasive monitoring systems and the presence of police officers and armed personnel in schools to ensure school safety measures do not create harmful learning environments or push students into the school-to-prison and deportation pipeline.

- Adopt the Texas CROWN Act and protect against racial and gender biases in school district dress codes, including discriminatory bans on hairstyles.

- Promote disciplinary policies that keep students in their regular schools and classrooms whenever possible instead of disciplinary placements in alternative programs or juvenile justice facilities.

- Require that schools meet the recommended student-to-mental health professional ratios (including counselors and social workers) and allow the school safety allotment to be used for these personnel expenses.

- Enhance discipline data reporting requirements to include data on discretionary referrals for code of conduct violations, English learner designation, homelessness status, and grade level. In addition, have the Texas Education Agency provide a data report to the legislature on a quarterly schedule.

- Raise the ages of juvenile court jurisdiction. Both the upper and lower ages should be increased so that 10- to 12-year-old children are not criminalized, and 17-year-old youth are not pushed into the adult criminal justice system

District leaders should…

- Develop schoolwide programs that build positive school climates and address the needs of all adults and students on the campus, without relying on punishments or criminalization. This includes modifying local codes of conduct to be fairer toward students’ safety and civil rights, without racial, gender or cultural biases.

- Expand the implementation of effective programs, including restorative practices and social emotional learning, and increase the presence of trained mental and behavioral health professionals like counselors and social workers.

For more information, contact Dr. Chloe Latham Sikes, IDRA Deputy Director of Policy (chloe.sikes@idra.org) or Ana Ramón, IDRA Deputy Director of Advocacy (ana.ramon@idra.org).

References

Advancement Project. (2019). We Came to Learn – A Call to Action for Police-Free Schools. Washington, D.C.: Advancement Project; Alliance for Educational Justice.

Bacher-Hicks, A., Billings, S., & Deming, D. (2019). The School to Prison Pipeline: Long-Run Impacts of School Suspension on Adult Crime. Working Paper No. 26257, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Council of State Governments Justice Center. (2011). Breaking Schools’ Rules: A Statewide Study on How School Discipline Relates to Students’ Success and Juvenile Justice Involvement.

Craven, M., Avilés, N., & Montemayor, A.M. (February 2020). How Schools Can End Harmful Discipline Practices, IDRA Newsletter.

Fisher, B.W., & Hennesy, E.A. (2016). School Resource Officers and Exclusionary Discipline in U.S. High Schools: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adolescent Research Review.

Gershoff, E., & Font, S. (2016). Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public Schools: Prevalence, Disparities in Use, and Status in State and Federal Policy, Social Policy Report, 30, 1.

GLSEN. (2016). Educational Exclusion: Drop Out, Push Out, and the School-to-Prison Pipeline Among LGBTQ Youth. New York: GLSEN.

IDRA. (2020). Sample letter to school district leaders on ending contracts with police and law enforcement.

IDRA. (2020). eBook: Resources on Student Discipline Policy and Practice, Third edition. San Antonio, Texas: IDRA.

IDRA. (2020). Unfair School Discipline – Discipline Practices in Texas Push Students Away from School – Web Story. San Antonio, Texas: IDRA.

Johnson, R. (November-December 2019). Texas Public School Attrition Study Highlights, 2018-19 – Attrition Rate Down to 21%, But Texas High Schools Lost Over 88,000 Students Last Year, IDRA Newsletter.

Latham Sikes, C. (February 2020). Racial and Gender Disparities in Dress Code Discipline Point to Need for New Approaches in Schools, IDRA Newsletter.

Ramón, A. (February 2020). Why Disciplinary Alternative Education Programs Do More Harm Than Good, IDRA Newsletter.

Startz, D. (January 14, 2016). Schools, Black Children, and Corporal Punishment, Brown Center Chalkboard.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. (2019). Beyond Suspensions: Examining School Discipline Policies and Connections to the School-to-Prison Pipeline for Students of Color with Disabilities. Washington, D.C.

Wilson, T. (February 2020). At What Cost? A Review of School Police Funding and Accountability Across the U.S. South, IDRA Newsletter.