By Chloe Latham Sikes, Ph.D. • May 2024 • See PDF eBook

For the better part of the last century, students, families and trained advocates have fought to ensure equal opportunities for all students to receive a quality education in public schools. The mark was set 70 years ago with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education that struck down racial segregation in schools and public facilities. The watershed case opened the schoolhouse doors to racial integration with the hope of improving the quality of educational opportunities for students of color and students with diverse backgrounds and educational needs.

For the better part of the last century, students, families and trained advocates have fought to ensure equal opportunities for all students to receive a quality education in public schools. The mark was set 70 years ago with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education that struck down racial segregation in schools and public facilities. The watershed case opened the schoolhouse doors to racial integration with the hope of improving the quality of educational opportunities for students of color and students with diverse backgrounds and educational needs.

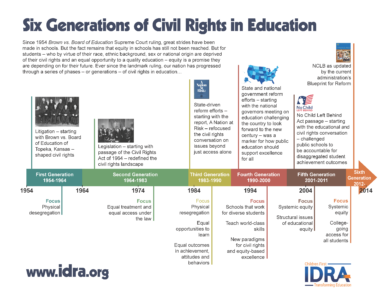

Over six “generations,” civil rights efforts in education evolved from focusing on racial desegregation of schools to securing equitable access and achievement for all students and later toward systemic equity, public accountability, and a heightened focus on college access for all students.

Over six “generations,” civil rights efforts in education evolved from focusing on racial desegregation of schools to securing equitable access and achievement for all students and later toward systemic equity, public accountability, and a heightened focus on college access for all students.

As we reflect on the legacy and lessons from Brown over the last 70 years and our steps forward, it is helpful to reflect on two related landmark court rulings that preserved students’ rights to educational opportunities and furthered good policy: Lau v. Nichols (1974) and Plyler v. Doe (1982). Brown offers arguably the most recognizable and secure building block for protecting students’ civil rights in schools.

Lau, now 50 years on the books, established students’ rights to access education in their home language.

And Plyler (42 years ago) ensured that all students, regardless of citizenship, can access free public education so that they may participate in and advance a democratic society.

Yet today, there are attempts to chip away or fully overturn the underpinnings of these landmark cases.

What Three Landmark Cases Mean for Civil Rights in Education

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate but equal” facilities were inherently unequal and violated the protections of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment (Brown v. Board, p. 495).

Seven years earlier, the ninth Circuit Court of Appeals similarly ruled, in the Mendez vs. Westminster case, that Mexican American children could not be denied a quality education because they were Mexican American. Thurgood Marshall co-authored an amicus brief filed by the NAACP. The subsequent 1947 ruling in Mendez and the California Board of Education ended segregation in California school districts. Marshall would go on to present similar strategies in his legal argument in the Brown v. Board of Education case.

The ruling in Brown overturned decades of de jure racial discrimination and led to school desegregation across the country, an effort that continues today in classrooms, campuses and across district boundaries.

It also paved the way for the Lau decision 20 years later, that determined students could not be segregated in schools based on the language they spoke.

In 1974, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Lau v. Nichols that a failure to provide English language instruction to students who do not speak English, or failure to provide them with other adequate and inclusive instructional procedures, is a violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The ruling expressed, for the first time, that students with limited or no English language skills must be afforded instruction to support their language development in order for them to meaningfully participate in the public educational program, and that a failure to provide this instruction violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964, “which bans discrimination based ‘on the ground of race, color, or national origin,’ in ‘any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance’” (Lau v. Nichols, p. 414).

The landmark decision also found that the public school system was ultimately responsible for determining how best to support “the varying characteristics of children rather than placing the burden on children to adapt to the characteristics of a single school program,” though it stopped short of defining how specifically schools needed to integrate these language supports in their curriculum.

IDRA founder, Dr. José Cárdenas, testified in the lower court case. And he and Dr. Blandina “Bambi” Cárdenas (no relation) served as consultants to the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice in preparing a brief that J. Stanley Pottinger presented to the Supreme Court on behalf of the plaintiffs.

After the Lau decision, Dr. José Cárdenas served on a federal taskforce to create guidelines for schools to comply with the ruling. In the decades that followed, the decision resulted in the implementation of a number of language support programs, such as bilingual instruction, sheltered instruction and English as a second language (ESL) programs.

In 1982, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Plyler v. Doe that all students regardless of citizenship status have the right to a free public education in U.S. public schools. The case consolidated several community lawsuits in Texas school districts. For example, a group of students and families brought a lawsuit against the Tyler ISD Superintendent for charging them tuition for public school enrollment.

In the Tyler trial, Dr. José Cárdenas served as an expert witness for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF). And IDRA’s now retired director of policy, Dr. Albert Cortez, testified in the Houston and Dallas court cases.

The high court’s ruling determined that the state of Texas did not have a compelling interest in discriminating against students who are not U.S. citizens by denying them public education.

These three cases and federal policies around inclusive and appropriate education provide a clear road toward ensuring students’ civil rights in education. The premise in Brown that separate is inherently unequal, and harmful, provides the foundation.

Each case focuses on securing equal educational opportunities for students across race, ethnicity, language and nationality. Together, they touch on the full provisions of public education from school access and assignment, access to educational programs and resources to the impetus for the state to inclusively fund and provide universal public education to students to prepare them for a strong future.

What These Cases Mean for School Programs and Students’ Civil Rights

Brown v. Board of Education concerned Black and Latino students’ access to quality public schools, reserved for white students. Yet Brown did not dictate how to desegregate schools nor how to provide for truly integrated education.

Today, the promise of Brown lives in school funding and budgets, student assignment and teacher diversity, as well as in debates on inclusivity, accuracy and racial representation in school curriculum and learning standards. But students still face a shortage of teachers of color, especially in subjects critical to advancing college and life readiness, such as STEM and bilingual education.

Inclusive racial representation extends beyond the teacher workforce to curricula, books, learning standards, and even courses. For example, AP African American Studies has faced political backlash and been discontinued in at least two states. Twenty states have passed censorship policies in K-12 schools to restrict conversations and lessons on race, gender and accurate history and current events.

This is a new era of information segregation.

Lau v. Nichols secured basic language protections in schools for students speaking a language other than English. For decades, bilingual education has held the tenuous promise of ensuring educational opportunity for emergent bilingual (English learner) students and enhancing students’ skills through bilingual, biliterate and bicultural educational opportunities.

Today, about 10% of public school students are identified as English learners (or emergent bilingual students). Texas serves the greatest proportion in the country, with emergent bilingual students accounting for 23% of public school enrollment. Emergent bilingual students account for 8% of Georgia public school enrollment. Texas and Georgia are both in the top seven states serving the greatest numbers of emergent bilingual students.

There is now an increasing prioritization of dual language immersion programs and multilingualism in schools that extends beyond the possibilities of just accessing English-language schooling. However, bilingualism cannot be treated as a commodity for those who can afford it. Substantive investments in bilingual education, teachers and students are needed to move toward linguistically inclusive schools.

In Texas and in Georgia, bilingual education is drastically underfunded. This affects the educational opportunities for emergent bilingual students, who graduate high school and access college at lower rates than their peers.

Plyler guarantees educational access for all school-age students within a district’s boundaries. It acknowledges that education is the critical foundation for social participation and democracy.

The case also contributes to the federal government’s acknowledgment of schools as sensitive places to avoid immigration enforcement, which include churches and hospitals. IDRA releases an annual reminder that students should be able to enroll in school without presenting proof of citizenship, and schools should remain safe sites for students and families to access. Yet some policymakers have voiced interest in overturning the Plyler ruling to scapegoat immigrant children and families for political gain.

Any challenge to Plyler would affect millions of children. Over 33% of Texas children and 22% of Georgia children have at least one parent who is an immigrant.

Tax estimates show that students whose family members are immigrants pay billions of dollars in state and local taxes to fund schools, roads, emergency services and other public amenities, despite being unable to access many state and federal benefits. Whether immigrant families have a legally recognized status or not, changes to Plyler could chill how parents enroll children in schools.

As IDRA has long believed all students are valuable, none is expendable. Each child must be able to access safe, welcoming and equal educational opportunities, no matter their race, ethnicity, gender, language, disability status, or citizenship status. We must keep the promise of Brown, and the promise of Plyler, and the promise of Lau.

Are We Entering a Seventh Generation of Civil Rights in Education?

As we commemorate the 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, it is important to consider the current landscape of civil rights in education and whether we find ourselves in a seventh generation. Brown paved the road for remedying systemic racial wrongs in education and society.

Today’s civil rights questions are concerned with both defending how far we have come and continuing to walk the road to achieve the promise of Brown, as exhibited by Lau and Plyler, for an inclusive and high-quality education for all children.

Yet our current educational system and political climate compel us to ask new questions about equitable access to educational opportunities. Along with partners like the National Coalition on School Diversity, the Century Foundation’s Bridges Collaborative and the AIR Equity Initiative at the American Institutes for Research, IDRA co-sponsored a convening this month to commemorate the 70th anniversary of Brown and consider some of these new questions.

Speakers considered current challenges to achieving Brown’s promise, or what speaker Matt Gonzales of the NYU MetroCenter called “rotten fruits of segregation,” including deep school funding disparities, persistent teacher shortages, censorship in curricula, lessons and books, and the devastating effects of the school-to-prison pipeline.

Today’s students require equitable access to information, online and in-hand, from qualified and certified teachers, yet face ongoing inequities in the digital divide, a rise in classroom censorship laws that restrict learning, and a persistent teacher shortage.

Students require well-funded schools yet face attempts to privatize public education dollars (a political and policy strategy that is, itself, a vestige of racial segregation in schools) (see School Segregation Through Vouchers).

And they absolutely must be able to walk through the school doors safely, without fear of deportation, in order to learn and thrive.

We have known for over 70 years what we need to do to ensure students have the freedom to learn together. Yet as U.S. Rep. James Clyburn of South Carolina posed as the convening’s opening question, “Will we ever develop the will and find the way to integrate?”

The seventh generation of civil rights in education contemplates these questions to consider new frameworks for achieving safe, welcoming and inclusive schools for all students. This is more than a question of physical facilities, of instructional materials, of coursework and of assessments and accountability systems. It is a question of how we value each and every child, their purpose and possibilities, and our commitment to their lifelong joy and success.

Learn More

Brown v Board of Education – The Law in Education, IDRA webpage with background and context info about the case and what followed

Podcast: The Law in Education – Brown v Board of Ed – Episode 223

Infographic: Six Generations of Civil Rights and Educational Equity

Webpage: Lau v. Nichols – The Law in Education

Lau v. Nichols 50th Anniversary Commemorative Event: Learn more and watch video

Podcast: The Law in Education – Plyler v Doe – Episode 224

Video of podcast 224: Plyler v Doe at 40 – Schooling Guaranteed for Immigrant Children

Webpage: Plyler v Doe – The Law in Education

Infographic: Welcoming Immigrant Students in School (English/Spanish)

Webpage: Education of Immigrant Children