• By Felix Montes, Ph.D. • IDRA Newsletter • November- December 2009

The Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program has achieved its 25th anniversary this year. With its less than 2 percent annual dropout rate in schools with dropout rates often exceeding 40 percent, the program has been highly successful. In a previous article, I outlined the instructional strategies constituting the five primary reasons for this success (See October 2009 issue of the IDRA Newsletter). This article explores the five supporting strategies that facilitate and improve the implementation of the instructional strategies.

The Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program has achieved its 25th anniversary this year. With its less than 2 percent annual dropout rate in schools with dropout rates often exceeding 40 percent, the program has been highly successful. In a previous article, I outlined the instructional strategies constituting the five primary reasons for this success (See October 2009 issue of the IDRA Newsletter). This article explores the five supporting strategies that facilitate and improve the implementation of the instructional strategies.

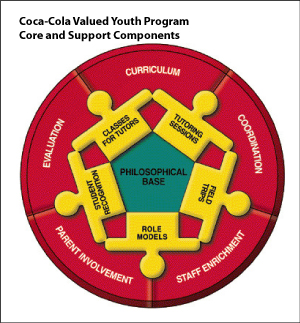

Many extracurricular programs offer outstanding interventions. What is rarely found though is the kind of programmatic support that sustains the intervention that is integral to the Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program. This programmatic support has five components: evaluation, family involvement, staff enrichment, curriculum, and coordination. Each of these elements is critical and necessary for the success of the intervention (Cárdenas, et al., 1992). In the program literature (see IDRA, 1990), these five elements are often depicted as an outer circle supporting the inner circle made up of the five core elements comprising the intervention: tutoring, classes for tutors, student recognition, field trips and role models – delineated in the prequel to this article.

Many extracurricular programs offer outstanding interventions. What is rarely found though is the kind of programmatic support that sustains the intervention that is integral to the Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program. This programmatic support has five components: evaluation, family involvement, staff enrichment, curriculum, and coordination. Each of these elements is critical and necessary for the success of the intervention (Cárdenas, et al., 1992). In the program literature (see IDRA, 1990), these five elements are often depicted as an outer circle supporting the inner circle made up of the five core elements comprising the intervention: tutoring, classes for tutors, student recognition, field trips and role models – delineated in the prequel to this article.

Evaluation is perhaps the component that most surprises researchers. The surprise is not that there is an evaluation component, but the extent and thoroughness of the evaluation provided by IDRA. Every aspect of the intervention is evaluated. Field trips and role models are evaluated by the tutors and the teacher coordinators. The implementation team uses these evaluations to improve both the way those activities are conducted and the selection of field trips and role models. Tutors also have an opportunity to evaluate these and all other aspects of the program in the post intervention instrument they complete at the end of the year. There, they evaluate their tutoring, the classes for tutors, and the student recognition events. In that instrument, they provide feedback directly to the teacher coordinator, and they evaluate their relationships with the rest of the school staff, their friends and family. These evaluations provide an important window into how the tutors’ perceptions have changed, as many of these aspects also are documented at the beginning of the year to establish a baseline.

Because tutoring is the heart of the intervention, it is evaluated through observations from different perspectives by the teacher coordinators, the elementary school tutee’s teachers, and IDRA trainers. These observations are conducted several times throughout the year.

The program has specific guidelines under which tutoring should happen. For example, tutoring occurs under adult supervision, often in the tutees’ classroom itself, as part of the regular class period. Three tutees are assigned to a tutor. There is at least a four-year age difference between the tutees and the tutor. Tutors set a plan for their tutoring supported by the tutees’ teacher. The observation constitutes a mechanism to monitor that these guidelines are followed, in addition to documenting the tutoring dynamics and providing recommendations for improvements.

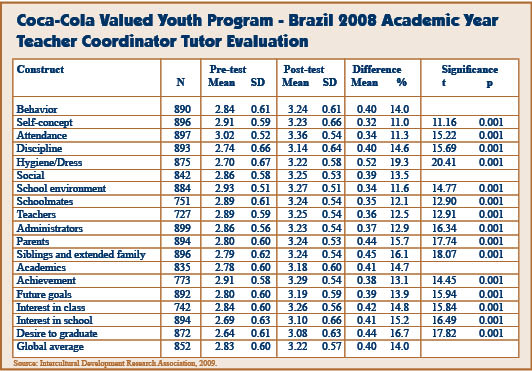

Since the tutors are the principle subjects of the intervention, they are evaluated extensively. In addition to their own evaluation contributions, as indicated above, they are evaluated by the teacher coordinator and often by other relevant staff, including the tutees’ teachers, on a pre-test and post-test basis. These evaluations provide a good sense of how tutors change academically, behaviorally and socially. They show the extent to which tutors have improved their relationships with their families, their peers and school staff. They also document their improved outlook on life and their desire to graduate and to continue their education.

The table below illustrates this aspect of the evaluation for tutors in Brazil, for example, where the program operates in 44 schools in 20 cities (in eight states) throughout the country. The evaluation shows that the tutors had significant gains in all three domains: behavior, social and academic (p < 0.001). In behavior, they had a 14.0 percent improvement overall, including gains in self-concept, school attendance, discipline, and hygiene/dress. In the social domain, the gain was 13.5 percent, which included improvements in relationships with the school environment, classmates, teachers, administrators, parents, siblings and extended family. The highest improvement was in academics (14.7 percent). The evaluators reported significant gains in academic achievement, future goals, renewed interest in their classes and school in general, and a stronger desire to graduate (IDRA, 2009).

Most educators and practitioners know today the importance of family involvement in their children’s education. Twenty-five years ago, it was one of the novel aspects of the Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program. Tutor families are involved in the program from the beginning. Of course, they need to approve of their children’s participation in the program. This is not just done by their signing a form. They receive detailed verbal explanations about what the program is and how they, as parents, will be involved.

Parents participate in many field trips and often are role models invited to speak to the tutors. This recognizes the contributions they make to the community and emphasizes the dignity of families. Parents participate in at least three enrichment sessions, focusing on needs they have expressed. These sessions are conducted in the language of the parents. In addition, individual family sessions with the teacher coordinator or family liaison are arranged to share with parents information important for their children’s education.

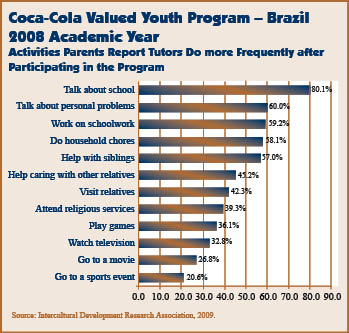

Throughout the program, parents foster a new partnership with the school to further their children’s education beyond high school. Parents also evaluate the program, providing valuable insights into how the tutors’ behavior has changed at home. They often report that the students become more responsible by helping more with home chores and with their siblings and elderly, and by spending more time talking about the schools and doing school homework. The box here shows an example from the Brazilian implementation. Similar results are found in the United States and in other settings.

Throughout the program, parents foster a new partnership with the school to further their children’s education beyond high school. Parents also evaluate the program, providing valuable insights into how the tutors’ behavior has changed at home. They often report that the students become more responsible by helping more with home chores and with their siblings and elderly, and by spending more time talking about the schools and doing school homework. The box here shows an example from the Brazilian implementation. Similar results are found in the United States and in other settings.

Staff enrichment is at the foundation of the program achievements. Through this support component, the implementers create a team committed to the program’s success, regardless of the prevailing conditions in the schools. The team is made up of the school principals (elementary and secondary), teacher coordinator, family liaison, evaluation liaison, and the tutors’ and tutees’ teacher representatives. Staff enrichment is achieved through technical assistance and training provided by IDRA. Although there are concrete training sessions, much of the staff enrichment happens on a continuous, collaborative working basis. This unfolds as the team meets to review the current status, plan the logistical elements of program operation, including student selection and placement, and use the curriculum framework to develop appropriate instructional activities.

During these meetings, there is an emphasis on understanding the concept of Valued Youth – what does it mean to value youth in a variety of contexts: inviting parents, selecting students, planning activities, and dealing with difficulties. As the team becomes more cohesive and a climate of success permeates their activities, participants start using formative and summative evaluation results to improve program implementation.

Ostensibly, the fourth supporting component, curriculum, prepares the students to become effective tutors. Through its student-centered activities, the emphasis on tutors’ sharing their own experiences and the use of current materials – often created by the tutors themselves – does much more. While it does improve the students’ tutoring skills, it also increases their literacy and more importantly enhances their self-concept and self-efficacy. Tutors regain the sense of being able to function in the school environment with whatever resources are available. This is substantiated through the holistic approaches the curriculum offers. Instead of concentrating on a particular subject to the exclusion of others, the teacher coordinator sees the tutors as young persons with diverse abilities and potentialities. Thus, a particular situation could be approached in different ways by different tutors, as they try to help the tutees in their own creative ways. The tutors drive the curriculum pace, as the teacher coordinator constructs lessons to respond to the tutors’ needs. Tutors learn important lessons about managing their activities, setting goals and evaluating results directly applicable to their lives, as they can visualize future careers, going to college and achieving exciting professional lives.

Coordination, the final Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program supporting component, brings everything together. The implementation team coordinates and monitors program activities, removes roadblocks, and extends the program valuing philosophy campus-wide as appropriate. The team makes use of various planning manuals and instruments to conduct a step-by-step implementation (see Robledo, et al., 2004). At least three full-team implementation meetings are conducted annually. In addition, regular weekly or bi-weekly meetings are conducted by the core team – the teacher coordinators and the tutors’ and tutees’ teacher representatives – to monitor day-to-day activities.

In summary, the Coca-Cola Valued Program re-establishes the student-school relationship through a mindful implementation of five sound instructional strategies (tutoring, classes for tutors, student recognition, field trips, and role models) designed to value young people for what they can offer and to empower them to improve those offerings. Through this process, the students regain the meaning associated with the school in their lives, and can then visualize themselves as future successful professionals (Montes, 2009). The instructional strategies operate efficiently because the program also has a set of five support strategies (evaluation, family involvement, staff enrichment, curriculum, and coordination) that guide implementation and monitoring, and provide the needed feedback for continuous improvement. Indeed, this 5 x 5 approach is at the heart of the program’s success during its 25 years and in the years to come.

Resources

Montes, F. “25 Years of Effective Dropout Prevention: Five Primary Reasons for the Success of the Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio,

Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, October 2009).

Cárdenas, J., and M. Robledo Montecel, J. Supik, R. Harris. “The Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program: Dropout Prevention Strategies for At-Risk Students,” Texas Researcher (Winter 1992) Volume 3.

Intercultural Development Research Association. Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program: Important Information for Schools and Agencies One Step Away from Implementation (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, 1990).

Intercultural Development Research Association. Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program: Brazil Evaluation Report, 2008 School Year – 10th Anniversary (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, 2009).

Robledo Montecel, M. Continuities – Lessons for the Future of Education from the IDRA Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, 2009).

Robledo Montecel, M., et al. Coca-Cola Valued Youth Program Implementation Guides: Elementary Principal Guide; Elementary Teacher Guide; Evaluation Guide; Program Administrator Guide; Secondary Principal Guide (San Antonio, Intercultural Development Research Association, revised 2004).

Felix Montes, Ph.D., is an education associate in IDRA’s Support Services. Comments and questions may be directed to him via e-mail at feedback@idra.org.

[©2009, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the November- December 2009 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]